There were three bullets, a cigarette butt and a fingerprint lifted from the sink faucet, plus a tiny hair in the ravaged cash register that could have belonged to anybody.

For nearly 50 years, the evidence sat in a vault at the FBI, untouched and largely forgotten by the police who put it there. That was all the evidence they had in the unsolved homicide of 49-year-old Everett “Red” Delano, the oldest cold case in New Hampshire.

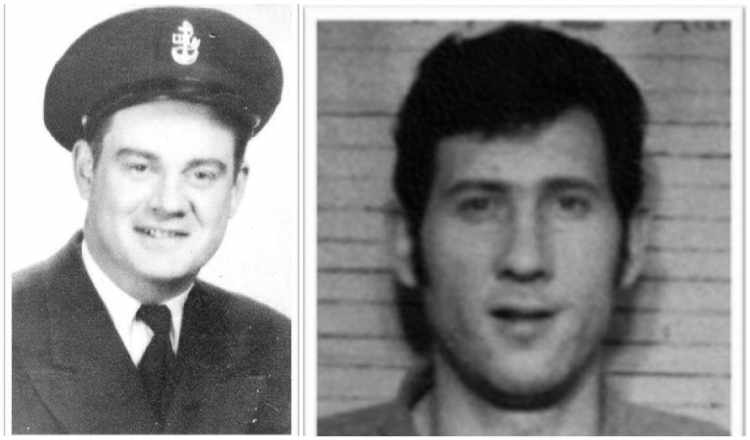

Delano, a Navy veteran and married father of three, was working alone at Sanborn’s Garage the morning of Sept. 1, 1966, when a thief shot him in the head three times, getting away with no more than $100. The cash register was left open behind the counter, with only pennies left inside. The water was left running in the office bathroom. His watch, shattered by a bullet, preserved the exact time of the crime: 9:35 a.m. A half-hour later, two teenage boys driving through the sleepy town of Andover, New Hampshire, and looking for gas pulled into Sanborn’s to find Delano bleeding on the floor.

By the end of the year, the case was cold. Police could not identify a single suspect.

But in 2013, a simple phone call from Delano’s family sprang the case back to life. Four years earlier, the New Hampshire Department of Justice had created a special cold case unit, and Delano’s family was wondering if they were close to solving his death. The answer, at least then, was no. The case was so old, police admitted, that the newly formed cold case unit had forgotten it.

The reminder from Delano’s family was all they needed to resolve it.

On Wednesday, the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office announced that authorities believe they have finally identified the man who killed Delano more than five decades ago: Thomas Cass, then a 20-year-old newly married, newly discharged military vet who would go on to amass a lengthy rap sheet for numerous robberies and weapons offenses.

Police say that as soon as Delano’s family inquired about the investigation, police discovered that the evidence from the original 1966 investigation had been preserved but never tested. The fingerprints left on the cold-water faucet were more than enough, police say. Because of Cass’s criminal history, his fingerprints had been entered into a nationwide fingerprint database known as the Automated Fingerprint Identification System, or AFIS. Once police entered the faucet prints into the database, they matched with Cass.

Still, although the case is now considered closed, there will be no charges.

Just before Cass could be arrested in 2014, police say, he committed suicide.

And now police argue that it’s evidence of his guilt.

In a 13-page report on the investigation released Wednesday, police say Cass’ choice to kill himself shows he intended to escape justice “forever.”

“Over the years, he had made it clear to those closest to him that he would never go back to prison,” the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office wrote in the report. “It is a fair inference that he killed himself to avoid going back to prison. … This conduct arguably reflects his consciousness of guilt, in that it suggests that he did not believe that he could defend himself against the murder charge and that he was escaping forever from the consequences of this murder.”

After matching his fingerprints, the New Hampshire State Police first reached out to Cass in the fall of 2013, while he was living in Orleans, Vermont. By then, he was 67 with a head of white hair. He had not been convicted of a crime since 2000, when he was caught manufacturing drugs in federal prison while serving time on an aggravated assault probation violation, according to the report.

He didn’t hide his rap sheet from the cops who showed up at his door, asking for his life story. He told them about the robbery at a gas station in Springfield, Massachusetts, that he carried out with a sawed-off shotgun, sending him to prison in 1967, and the time he stole a car in Vermont and drove it to New Hampshire. But other than that joyride, he told them, he had only been to the state once, and surely had never been inside any Sanford’s Garage in Andover.

The investigators didn’t tell him about the fingerprints that put him at the scene.

But that interview was a start. Police continued talking to his family and friends, seeking to develop a fuller picture of the man who introduced himself as a “businessman and a crook” when he met his first wife in the 1960s, as she told the investigators.

“She stated that he was proud of his past criminal career and would boast about it,” the report notes. “She believed that he would hurt people to get what he needed.”

His first wife told the police stories about Cass entering a home and terrorizing a family inside, and how after numerous threats he made to her, she got a restraining order against him and then a divorce. Another of Cass’ ex-wives told authorities stories about Cass and his friends bragging about killing a man who “knew too much” in the 1970s, and Cass leaving the house with a gun to retaliate against a man who owed him money. She told them she had witnessed him beat people brutally.

The police returned to interview Cass on Feb. 20, 2014, this time unannounced. They told him that forensic evidence found at the scene made police certain that he had been there before. Did he want to come clean?

After saying it was “possible” he had been at the gas station, Cass stopped talking and asked for an attorney.

Four days later, according to the report, he bought a gun and shot himself in the head.

New Hampshire courts have ruled that prosecutors can introduce suicide attempts during trials as evidence of guilt, just as they would if a suspect fled police. And the attorney general argues that ruling should be no different for Cass.

It’s unclear why it took police five years after his death to conclude he was the suspect and close the case. But investigators continued interviewing those who knew Cass until as recently as November, piecing together the end of his life.

Just after cold case unit investigators contacted him, he amended his will, according to the report. His live-in companion, Jane Spainol, told investigators that he made clear to her that he did not want to “die in a square box.” In her 911 call on the day Cass committed suicide, she told the operator he “believed that police were coming to arrest him in relation to a cold case investigation,” according to the report.

But most telling of all, police claim, was what he told her just after one of his original interviews with police.

He assured Spainol that he had nothing to do with any robbery or murder at a gas station in 1966.

Then, he added, “You never talk about something that has no statute of limitations.”

“This statement is arguably an admission of guilt,” the attorney general wrote. In New Hampshire, the only crime for which there is no statute of limitations, the report notes, is murder.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.