White-nose syndrome came to Maine at the start of the decade. Its effect on the bat population has been stark since then.

Since its initial appearance in New York in 2006, WNS has spread to 33 states and seven Canadian provinces. It first arrived in Maine in about 2010 or 2011, said Shevenell Webb, a furbearer and small mammal biologist for the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife.

Oxford County was the first to be affected in Maine, followed later by Piscataquis and Hancock counties in 2013.

According to Webb, the fungus grows on the skin tissues of hibernating bats in the winter. This rouses them from hibernation, causing them to consume their winter fat stores and starve before spring.

The disease has been found on 12 different species of bats, including the Indiana bat and gray bat, which are both endangered.

In Maine there are eight species of bats — three known as tree varieties that fly south during the winter and five kinds that live in caves. Tree bats are not affected by white-nose syndrome, because it only afflicts those that hibernate in cold, damp caves.

Webb said one of the most common bats in Maine was the little brown bat, but because of the disease, they are seen much less often.

“There was a pretty instant decline from the white-nose syndrome disease,” she said.

When bats hibernate, Webb said, they spread the fungus from one animal to another. Then, when bats travel from cave to cave, they spread it even more. When people visit these caves, fungus can also be moved by traveling to other places on their shoes and clothes.

Maine has a policy that bans people from visiting these caves where bats hibernate from Oct. 1 to April 30 to protect the bats. There are also gates that block people from getting into caves but allow bats to get through.

Inland Fisheries & Wildlife biologist Shevenell Webb collects a listening device Tuesday at the Merrymeeting Bay Wildlife Management Area in Dresden that collects the ultrasonic sounds of bats. The agency is studying the population of the mammals that were prolific throughout Maine but have declined due to white-nose syndrome. Kennebec Journal photo by Andy Molloy

To track the population of bats, the state Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife uses passive surveys, similar to a game camera, that track the frequencies of the bats for two or three weeks. These surveys assess how populations are doing across the state.

“Most people don’t see bats flying around in their backyard like they used to,” Webb said.

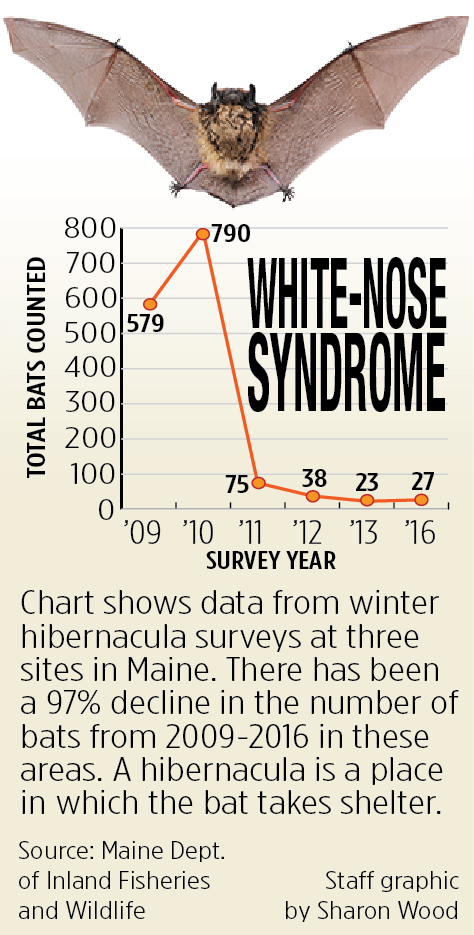

She estimated that the bat population has declined by 97% in Maine. A survey done of bat hibernacula, places in which they take shelter, counted 579 bats in 2009 and 790 in 2010. One year later, in 2011, that number had dropped to 75 and was at 27 in 2016. The surveys were done annually until 2013; they are now undertaken every three to five years because researchers do not want to disturb the bats.

“There’s a long, sad list of species that have been affected or damaged by species like this,” said Erik Blomberg, a professor at the University of Maine. “But this is pretty unprecedented.”

Though there is no cure for white-nose syndrome yet, ongoing research and studies are looking at possibilities.

One option for a cure, according to the White-Nose Syndrome Response Team’s website, would be to vaccinate bats in the wild. Another option is to use chemicals to prevent the disease from spreading on either the bats or the caves in which they live.

Finding a cure would be beneficial not just for bats but for biodiversity.

“Bats provide a lot of benefits to the environment,” Webb said. “And most importantly, they eat insects.”

A single bat can eat up to its weight in insects each night, she said, which is something of which people are appreciative. In other parts of the world, there are bats that eat fruits and are also pollinators, so plants rely on bats.

“Every individual (bat) matters,” Webb said. “Bats help in a lot of ways.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story