Human beings are inordinately attached to our stories – narratives about our family, our culture, the events that shaped our lives, who we take ourselves to be, who society says we should be. They are essential tools in forming our identities, and there is great value in them.

At the same time, stories also have a way of concretizing a self image, which can then limit our perspective to our immediate earthly experience, closing us off to larger possibilities. These types of stories obscure something less tangible yet more authentic about us: that of our essential being, outside of any confined egoic preconceptions.

The desire to break free of narrative constrictions is what impelled Shiao-Ping Wang to abandon representational art for an abstraction that is nevertheless rooted in very real things, such as I Ching hexagrams, Chinese knotting and various designs of Chinese lattice windows. Selections from this body of work are on exhibit in “Shiao-Ping Wang: Air & Sound” at Buoy Gallery in Kittery (through Feb. 13).

Wang was born in Taiwan, to parents who had emigrated there from Northern China. Because of this, she never knew her grandparents or had any true immersion in the regional customs, rituals and outlook of that culture.

More painful still was the fact that Chiang Kai-shek’s breakaway followers represented only 14 percent of the island’s population, who were mostly Southern Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong. This meant that Wang’s parents (and Wang herself) were referred to, not without derision, as “Mainland Chinese” by native Taiwanese.

Already an outsider, Wang felt further deracinated in New York, where she studied painting. Her early work, in some ways, sought to reconcile her family’s, and her own, multiple migrations through narrative painting.

Displeased with the results, she decided to dissociate herself from stories of any kind 20 years ago and began painting copies of Chinese lattice window screens she discovered in a book. This began to dislodge the grip of her identity, creating a more neutral, open ground through which to explore the deeper dimensions of her psychic split.

Looking at these works now, it seems clear that the underlying geometry of the lattice became a kind of scaffold – increasingly stylized through color variations and texture – that allowed her to approach at least a semblance of resolution among the disparate parts of her consciousness. This process of resolution is ongoing, as it is for most of us. Abstract painting is her medium for that process, where others might seek spiritual or psychological work, refuge in nature, and so on.

No painting seems more explicit about this methodology than “Summer.” It is a grid that superficially might appear like an abstract view out a window. Certainly, there is an intimation of warm seasonal light and of a verdant scene, most apparently leaves on an enormous tree.

But look closer and you will see great variety in the colors and the application of paint within each rectangle of the grid. Each has brushstrokes that are uniquely more or less discernible, and each has a greater or lesser profusion of white or blue or green than its adjacent rectangles or, if you will, “panes.” Each pane is outlined in a different color, perhaps indicating separate parts of an as-yet-unresolved whole. Yet the ground image beyond the panes does convey a deeper overall harmony.

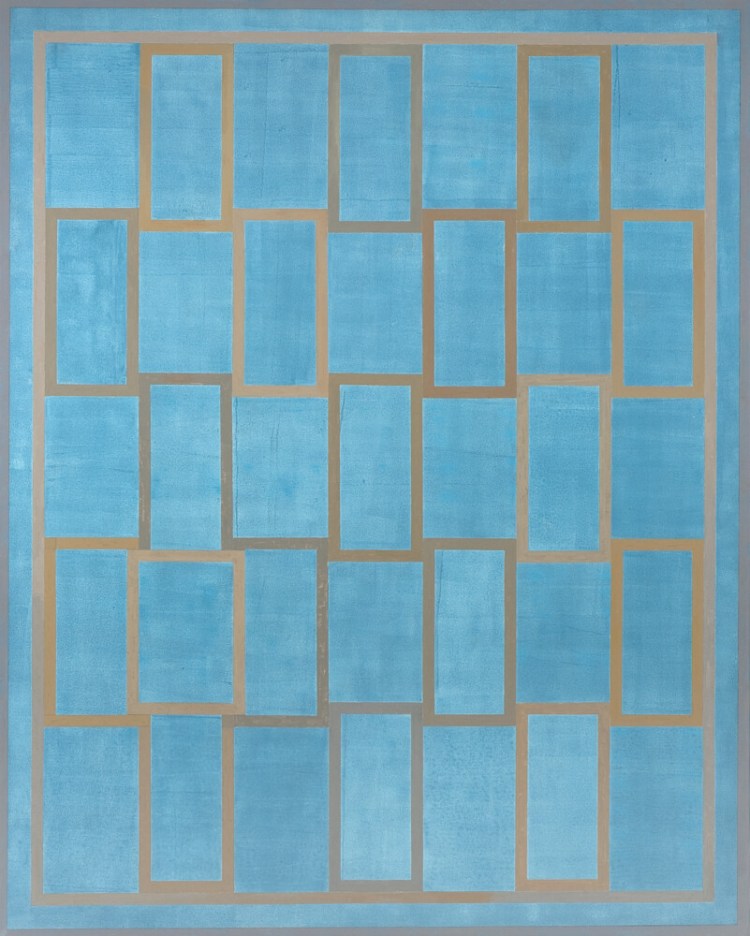

Other works, such as “Blue Air,” require careful scrutiny to see that, even when the color underneath the grids is essentially the same shade, it can appear mottled, especially with changes of light conditions within the gallery. These form the “Air” component of the show’s title in that they are ever-changing, moving and, in the end, not entirely graspable – like our more fluid, adaptable fundamental selves. They speak to us at a completely subliminal level devoid of story. There is something free and mutable about these richly pigmented grounds.

The “Sound” paintings are palpably musical. “Vesper” appears at first like a grid of targets a la Jasper Johns. But the shapes are actually derived from patterns of a harmonograph (a pendular apparatus whose movements trace patterns in sand or on paper), or concentric sound vibrations emanating from the tines of a tuning fork.

Superimposed on this grid is another looser grid of circles. Yet Wang has painted these circles in such a way that they appear to move from the surface into the radial target patterns, traveling into and below them, then reemerging again on the surface. It is a visual equivalent of the meandering aural paths that musical phrases can take, crescendoing to a dominant motif before being subsumed in the larger general timbre of the orchestra.

Repetitive spheres arranged diagrammatically in works like “Ancient Aquifer” or “Ensemble” at first showed up in Wang’s mind as what she thought might be phases of the moon. She soon realized, however, that their arrangement echoed the hexagrams of the I Ching, a Chinese system of cleromancy or divination.

This sort of subtle cultural touchstone also informs a series of works in a back gallery. They depict meandering lines that might seem at a casual glance to echo Brice Marden’s paintings of similarly random lines. Yet they are inspired equally by the ancient craft of Chinese knotting and the weaving of Anni Albers. (Wang says she derives far more inspiration from crafts and architecture than the work of other artists.)

Once we know this, these paintings like “Sorrow” could feel as if they teeter on the decorative. However, I’m not entirely convinced that Marden and Wang have dissimilar aims. Marden wanted to evoke mystical experience through the creation of abstract space. All his streamer-like configurations of line were, for him, really always the same line, stretching out infinitely and then infinitely weaving back in on itself.

For Wang, the weaving/knotting metaphor turns out to have resonance if we view them as different strands of her consciousness arising and intertwining endlessly. They are all here, all at once, completely connected. At the same time, they are all part of the same unity of who and what Wang is. There is nothing left to resolve if all can coexist in peace, as they do beautifully in these works.

Sometimes Wang will partially erase a line or cut into the paper and peel off a layer from a length of line. From the perspective outlined above, this could indicate points of losing our way, wandering off the path of our self-realization, or of discovering something under a surface that we did not expect.

Or maybe it’s all just grids, circles and squiggles. There is unity and resolution, however, to the way they hold together.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.