The Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s “CMCA Biennial 2023” (through May 7) has been put through the publicity ringer for the wrong reason. The Press Herald published a front-page story on a so-called “controversy” over the initial placement of a first-generation Chinese artist’s work in a hallway adjacent to the public bathrooms, to which its multidisciplinary author, Evelyn Wong, took great umbrage.

This is a great pity because biennials are frequently grab bags that presume to say something prophetic about the state of art today, yet this exhibition gets so many things right. Not only is it replete with truly excellent work in many media and from an array of cultural perspectives, but it also includes intriguing surprises and artists not on the list of usual suspects who are constantly shuffled around the Maine art circuit.

First, the controversy. The initial location offered the Portland-based Wong for her work, “The Year of the Rabbit,” was a hallway connecting the main exhibition spaces to its ArtLab and offices. It is, indeed, adjacent to a vestibule leading to the public restrooms. The other side of this wall is floor-to-ceiling glass that looks out onto the CMCA’s public courtyard. When Wong complained about her placement, the museum apologized (though it has every right to install art as it chooses) and agreed to move the work to a temporary wall in another gallery.

The work itself features two banners of Cantonese characters that translate as “Take Down White Supremacy” and “Institutional Equality for People of Color.” In an angry statement on her website, Wong accuses the CMCA of being “complicit in upholding white supremacy” and perpetuating “harm through curatorial decisions,” decisions she claims “disregard our very histories.”

We are living in exceedingly tumultuous times that force us at almost every level to confront old prejudices and attitudes about privilege, racism, cultural and sexual diversity, misogyny and other important issues. I have long maintained that this is a good and necessary thing. I also recognize that emotions are raw and tempers high, and that there is a lot of reactivity on every side of every argument these days. Regarding this controversy, however, I think Wong’s argument is specious.

To believe her claims, you’d have to buy into the assumption that culturally biased oversight was involved at best, malice at worst. It is a charge easily leveled at many institutions, but not the CMCA. Since taking over two years ago, director Tim Peterson has substantially expanded the representation of BIPOC artists exhibited, even making this a cornerstone of his leadership; out of 10 solo shows under his direction, seven have been non-white artists.

Peterson has also said to me that he sees the hallway and lobby as vehicles through which the museum becomes accessible and inviting to all, regardless of whether someone pays admission and actually comes in. This area is visible to everyone – all day, every day. The work of many artists has been featured in that hallway, most recently that of Ian Trask, a straight white male. Does that constitute “upholding white supremacy”? Furthermore, Trask’s show ran concurrently with a collaborative exhibition by Dan Minter and Eneida Sanches, two artists of color. If the CMCA were upholding white supremacy, wouldn’t it have been Sanches and Minter who were “relegated” to the hallway?

The last thing I’ll say about Wong’s controversy is that where her work ended up after her complaint is far less favorable to the piece itself, which now requires artificial lighting and feels cramped. It sacrifices light and visibility – not to mention an opportunity for her piece to actually draw people into the museum. Beyond these, its intensions are now diluted by an add-on to “The Year of the Rabbit” that Wong describes as “a replica of the floor plan sent to me from the CMCA, with the toilets of the public bathroom set in clear vinyl against a section of gold-painted wall.” The addition unintentionally diminishes the work to a one-note protest piece.

Rebecca Hutchinson. Boulders in Nets, 2020 Sisal thread, upholstery thread, clay, rope, clay soaked upcycled book pages, and wooden block and tackle, CMCA Biennial 2023. Courtesy of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art

Moving on to the art … 35 artists have work in this show, a selection culled from 423 applicants. Wong’s piece, regardless of her skirmish with the CMCA, certainly jibes with the observation of juror Misa Jeffereis, associate curator at the Contemporary Art Museum of St. Louis, that these artists are “reflecting the pivotal moment in which we exist – the societal inequities we push against, our understanding of time and our transience on Earth, the drive to understand one’s identity and lineage, and our relationship to the environment and our place within it.”

In contrast to Wong’s cri de coeur is the sublime, highly personal work of Hope artist Elaine Ng, whose various wall sculptures explore the “fingerprints” of place – that is, what makes a place unique. In this case it’s Taiwan, her mother’s homeland. Though she uses materials common to many urban environments (particle board, concrete, brick), Ng’s practice of constructing her pieces is layered with personal references about the way she interacts with the island and the various layers of her identity inherent in and through it.

Though specific references are mostly indecipherable to the viewer, Ng’s idiosyncratic mixing of materials implies layers of meaning, particularly those that incorporate diaphanous textiles that hint at the way we construct our public identities so that certain elements emerge only when we summon them or feel safe to show them. The wall sculptures exude a touching vulnerability and tenderness.

Jared Lank’s affecting video “Bay of Herons” records the nature of Mackworth Island and the ruin of the infamous abandoned school for the deaf, where sexual abuse of students ran rampant. As the camera pans across the school, a caption appears: “There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolize.” Observing the nature that is slowly reclaiming this human aberration on the land, another caption reminds us that “In nature, nothing exists alone.” This Portland artist’s video speaks about so many things: humanity’s impact on nature as well as nature’s persistence, segregation and mistreatment of people categorized as “other,” the cycles of life and death. It is mournful and beautiful and thought-provoking all at once.

Jeffereis’s fellow juror – Sarah Montross, senior curator at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Massachusetts – notes another trend among the artists represented here. “There is a certain fragility and resourcefulness within this Biennial: artworks that resemble or use scrim, string, patchwork, and connective tissues. There are cast-off parts or fragments brought together through collage and assemblage.”

Geoffrey Masland. Nothing’s the matter with the stars, 2021 Paper collage and acrylic on four panels, CMCA Biennial 2023. Courtesy of the Maine Center for Contemporary Art

This sense of connectivity certainly applies to Ng’s work. But one enormous (literally) surprise is Geoffrey Masland’s “Nothing’s the matter with the stars,” a 70-by-78-inch collage painting made from an image rendered with acrylics and collaged over by thousands of scraps from old books. The sense of creating new visual narratives from old written ones is, in itself, a rich idea. But to see collage at this scale – and the incredible contrast between dark negative and light positive space, or an essentially simple scene represented using such a profusion of material – is even more astonishing when we learn that Masland, who is based in Yarmouth, is self-taught. He is an artist worth watching.

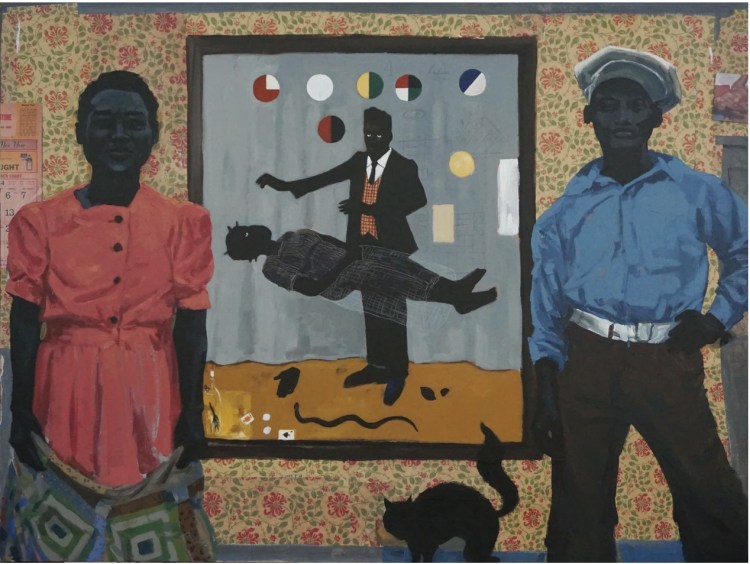

Another artist who combines paint and paper is the one-word New York-based artist Ransome (he has spent many summers in Maine). His reasons are different, meant to evoke the resourcefulness of African-Americans, who often created art and daily objects from whatever they could get their hands on. In “Invisible Artist,” the face of a Black woman in a polka dot dress is barely visible against an all-black ground. Above and to the left of her is a quilt reminiscent of the handiwork of the women of Gee’s Bend.

Of course, the title refers to the invisibility of Black and Brown people generally, as well as Black and Brown artists who, until recently, have been largely left out of the American art narrative. But the quilt also can be perceived as a window — to freedom, to other possibilities. Ransome’s work is heavily influenced by African-American music. In a way, his paintings also free-sample the art of many Black artists. We can see influences of Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Reggie Burrows Hodges, Kerry James Marshall and Kehinde Wiley. But the way Ransome synthesizes all of these is unique and makes a case for art that’s just plain beautiful, even when it is loaded.

Mandana MacPherson + Gigi Obrecht. Rubberscape, 2023 waste inner tubes, wood, cardboard, tire crumb rubber, glass, metal, local sand, found and salvaged materi – als and objects , paper from 100% salvaged cotton, CMCA Biennial 2023. Courtesy of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art

Many, many others are worth mentioning. Among them: The Freeport art collaborative of Mandana MacPherson and Gigi Obrecht, who find endlessly inventive potential for rubber as an art material, and Rebecca Hutchinson, a Rochester, Massachusetts art instructor with deep connections to Maine art schools. The outsized presence of Hutchinson’s hanging sculptures balances ideas of structure and craft, implied weight versus lightness (each weighs a mere seven pounds).

Holden Willard. The Lovers, 2022 Oil on canvas, CMCA Biennial 2023. Courtesy of the Maine Center for Contemporary Art

Union-based Alanna Hernandez’s extraordinarily rendered pencil-on-wood works explore with deceptive ease and rhythm the interruption of trauma on our sense of flow. Young Portland artist Holden Willard’s sumptuously painted “The Lovers” manages to convey passionate emotion while simultaneously acknowledging how quickly it passes. South Portland artist Philip Brou meditates on time in his installation of 196 ink drawings of places he passed while on his daily runs, each made in approximately the same time it took to jog by them.

It’s way too much to take in during a single visit. Fortunately, the Biennial runs for quite some time, hopefully way past the time it will take for the current “controversy” to blow over. I look forward to the luxury of multiple return trips.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story