Cubism is complicated. It is hard to understand and even harder to explain. But what sets Cubism atop the most important movements in Western art is the incredible range of practices it set in motion. Abstraction, Constructivism, Futurism, Dada, assemblage and collage are Cubism’s legacy.

Some of these are indirect. For example, Cubism never crossed into abstraction since it was fundamentally about legible description – the very antithesis of abstraction. But some artistic inventions, like collage, were put to use in Cubist paintings. Georges Braque, who along with Picasso comprised the original Cubist duo, invented collage as an element of painting in 1912.

The term “collage” is derived from the French word for glue, and it is the practice of gluing things – paper in particular – to a canvas or other painting support.

For some reason there has been a spate of major collage exhibitions in Maine in 2014. The Bates College Museum of Art early this year hosted an explosive collage survey, “Remix: Selections from the International Collage Center,” and the Center for Maine Contemporary Art sponsored “Collage X 10” at the Portland Public Library’s Lewis Gallery in March. The latter, organized by the center’s curator emeritus Bruce Brown, featured the works of 10 Maine artists.

While her collage exhibition had been on the schedule for a year and a half prior, University of New England Art Gallery director Anne Zill worked with Brown to incorporate his selected artists while growing the roster to 25. It was an effective approach; while “Collage X 10” was a worthy introduction to the practice of collage in Maine by active professional artists, “Making a New Whole: The Art of Collage,” is a more expansive cross-section. It is an impressive show that makes the case that collage is a significant pictorial practice in Maine.

Visually, it is a very strong show. And this is important because “Art of Collage” (the title smartly echoes the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal 1961 exhibition “Art of Assemblage”) does not make a clear statement about collage in Maine. Instead, it shows that it is a robust practice – a point only reinforced by the fact that accomplished artists such as Andrea Sulzer, Duane Paluska, Tom Paiement, Lauren Fensterstock and Jeff Woodbury, among so many others, weren’t included.

What is most striking about “Art of Collage” is that collage is presented as a side project of many of the included artists. This, of course, is invisible to anyone who doesn’t know the artists in the show, but it’s a pervasive theme.

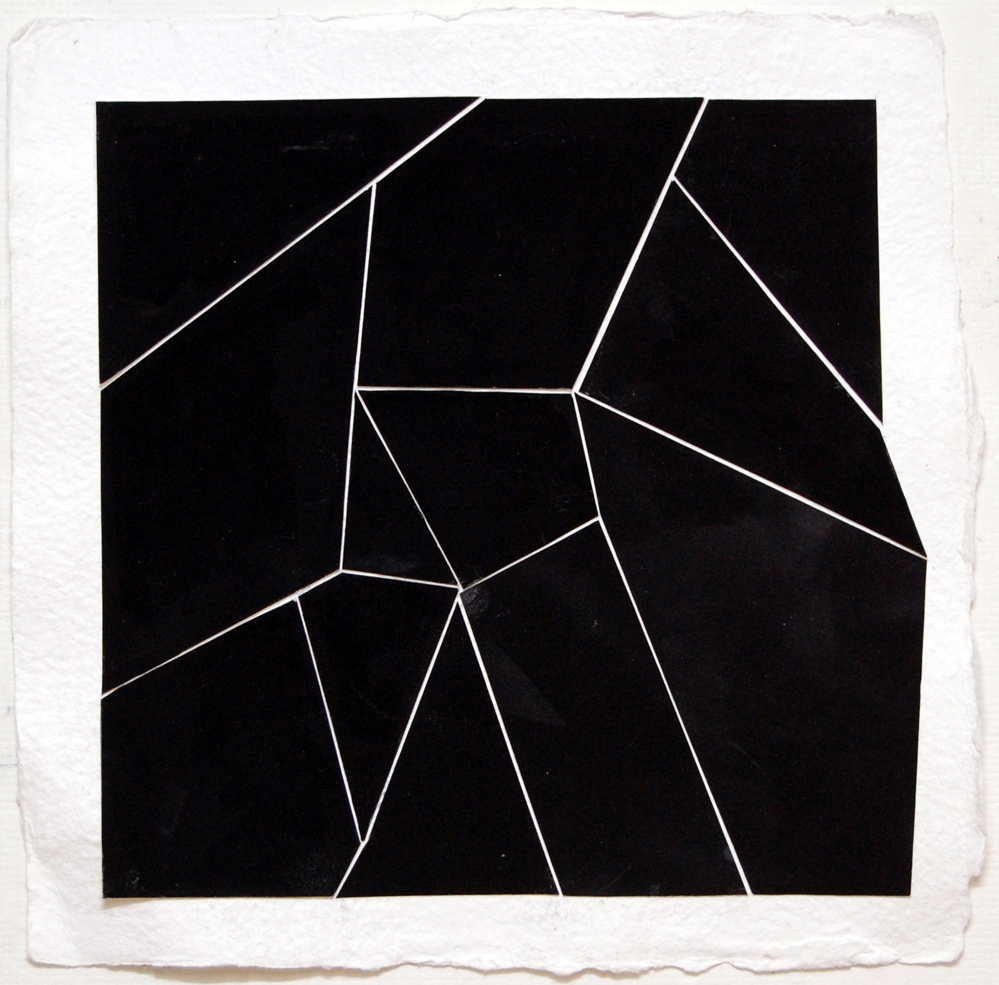

I just saw a terrific show of Avy Claire’s paintings in Blue Hill at the Cynthia Winings Gallery, and I have written in the past about her drawings. Noriko Sakanishi’s collages are an important component of her work, but she is best known for her sculptural wall constructions. Ken Greenleaf’s drawings and paintings on paper typically use their paper support as a spatially vague arena in which they perform pulsing, rhythmic motions, so his new collages of cut geometrical forms in matte black gouache on thick, handmade paper mark a radical departure. I knew Justin Richel’s drawings and excellent ceramic installation at the Portland Museum of Art Biennial, but his fun collages are phenomenal.

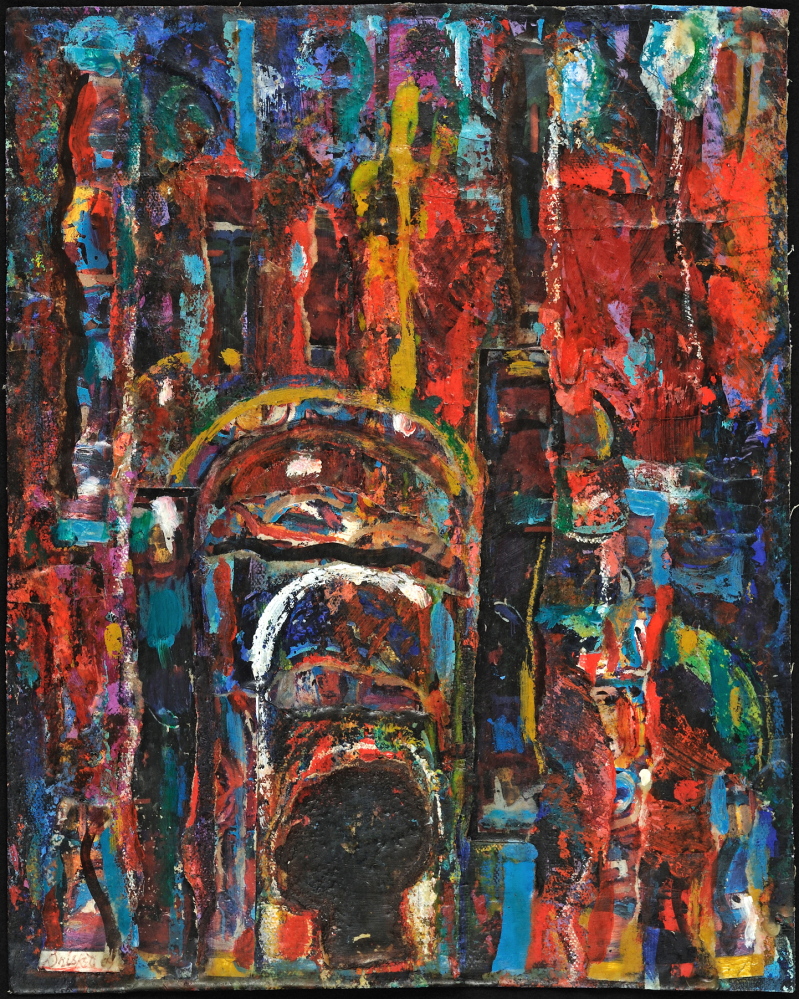

David Driskell is internationally renowned as a painter, but his collages represent an approach that brings him closer to Romare Bearden (and, yes, I asked Driskell about this). They also allow him to ratchet up his color density in smaller scale work – since color, rather than shape or drawing, is the driving force behind his compositions.

While some of the most impressive works were by artists with strong histories in collage – like Penelope Jones’ exquisite, painterly gems – many of the strongest works are by artists I didn’t realize work in collage. For example, no Maine artist interests me more than Gabriella D’Italia and yet I had never seen her collage work until “Collage X 10.” Her two horizontal abstract landscapes in “Art of Collage” exude a physicality unlike any of her other work.

I have always associated collage with painting – from Cubism to Matisse’s “cut-outs.” Even later works that look more like assemblage (which is more about objects and so is therefore closer to sculpture) are often specifically engaged with painting. Think of Robert Rauschenberg’s seminal “combine paintings” of the 1950s or Frank Stella’s wacky whale works.

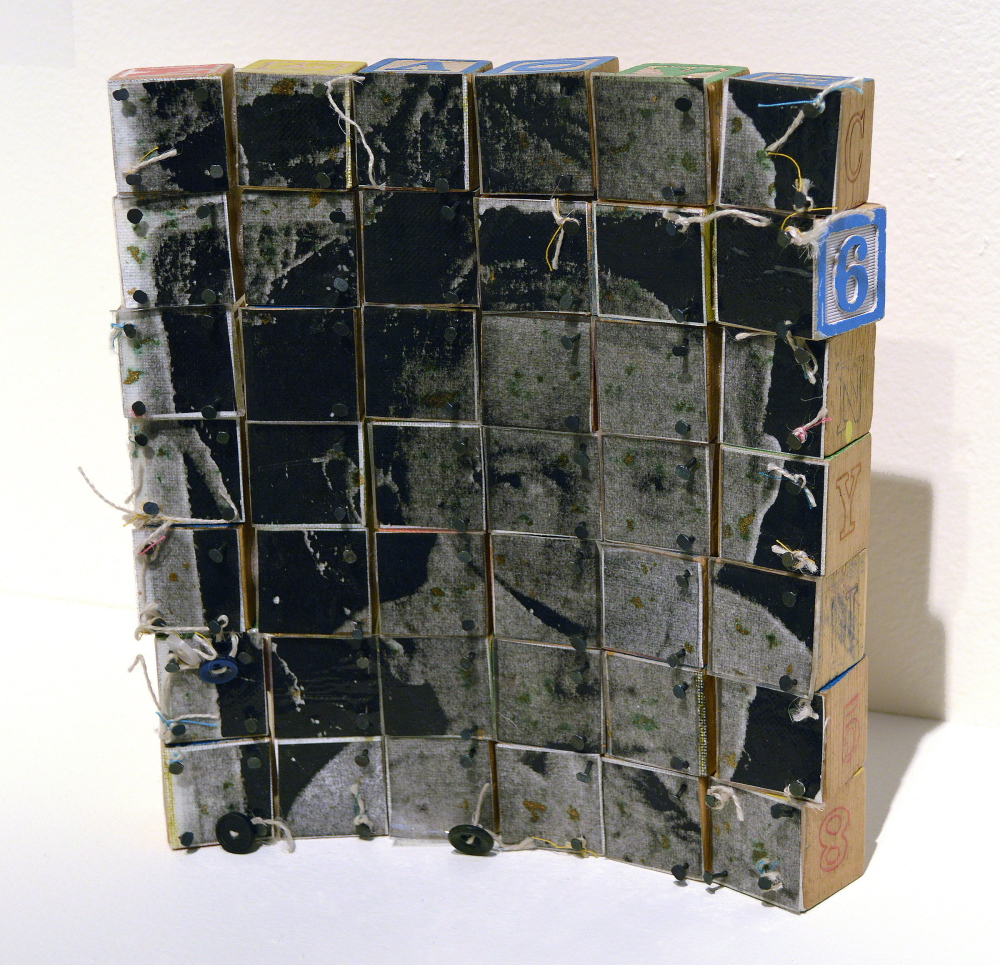

While “Art of Collage” follows collage as a painterly practice, several of the artists’ work is generally closer to assemblage than collage. Gail Skudera’s work is an example, though its focus on painting makes it an excellent fit for the show. Her “Block Portrait” in particular smartly engages the idea of the pictorial support, its elements and its qualities as an object.

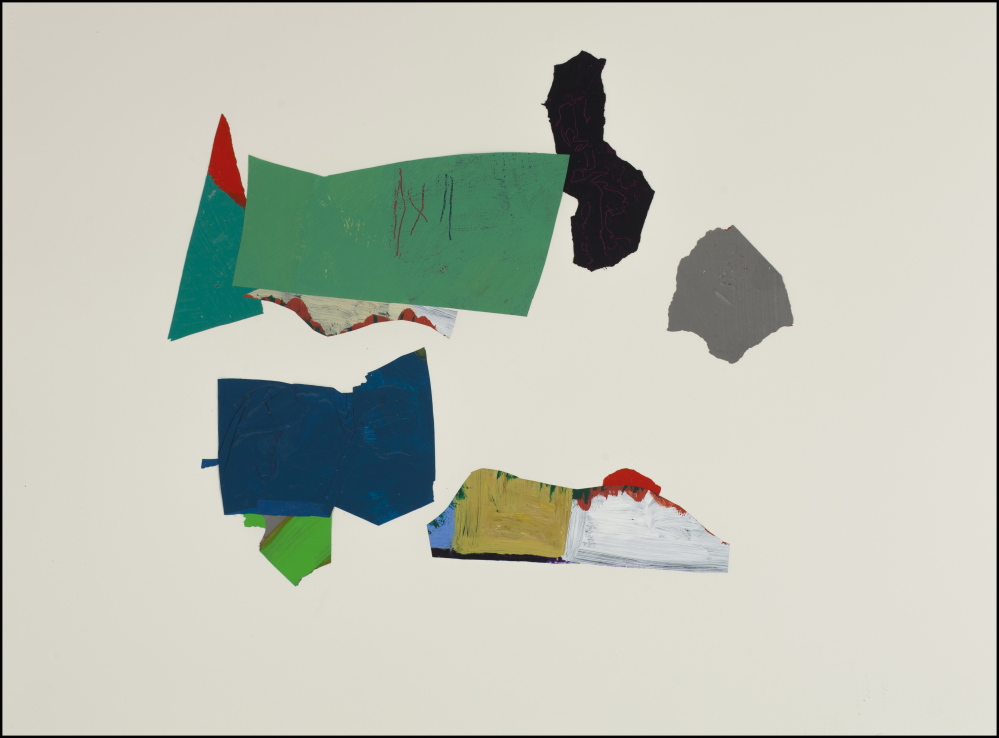

“Art of Collage” also held some exciting discoveries for me. I hadn’t known the work of Margaret Nomentana or Brad Woodworth, for example, and nothing in the show is more handsome than their best pieces. Nomentana’s four framed works feature patches of acrylic paint peeled from one surface and then arranged on and glued to a paper support. Nomentana’s and Woodworth’s work – old-school collage, in the style of the approach’s early champion, Kurt Schwitters, and his small-scaled works – are less striking for how they were made than for the extreme sophistication and elegance of their design sensibilities.

Because of its scale and relative strength, “Art of Collage” is an extremely satisfying show. (Why dwell on the weaker works when there’s so much good stuff to see?). And if the goal was to represent collage as a major part of art in Maine, then it is a successful show as well.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.