The year 1534 was crucial to the history of the United States of America.

It was then that the first Act of Supremacy was instituted. These acts granted King Henry VIII royal supremacy over England and established the Church of England, thus severing all ties with Rome. It was in this legal, religious, governmental and cultural context that the Puritans came to be, including the ones who came on the Mayflower to what is now New England.

In England, the Pilgrims’ religious practices were considered sedition. They were forced to flee in secret to Holland, where they experienced the functional separation of church and state – which they imparted to one of our country’s three fundamental founding documents, the Mayflower Compact.

But in 1534, government, religion and culture got bundled together for our nation-to-be in one omni-powerful package: the Crown.

Walking into the Berger Collection exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art, you are greeted by royal portraiture: Anthony van Dyck’s “Dorothy, Lady Dacre” (ca. 1633). Van Dyck was born in Belgium but became the most influential portraitist in English history as well as the principal painter to Charles I. Along with John Singer Sargent (oh yes, he’s here, too), van Dyck is my favorite brush handler in history.

While “Dorothy” isn’t van Dyck’s best, it’s still a phenomenal painting. Dorothy’s hands strike the always recognizable van Dyck poses. Her widow’s peak cap is handled with exquisite delicacy, as are the lace and drapery of her dress, and there is depth to the scene. Dressed in mourning, she is still a beautiful young widow with a life ahead of her. The label copy mentions the double rose with one blossom and one bud, but this metaphor is expanded by the past-oriented tapestry behind her to one side and the window open to a flourishing garden on the other.

When you turn around from the van Dyck, you find yourself looking at an incredible thing: An extraordinary English religious painting from about 1395, “The Crucifixion.”

We remember the Nazis burning Jewish books. We lament Savonarola’s 1497 bonfire of the vanities and the sacking of Britain by the Vikings. But we conveniently forget that with the formation of the Church of England, Catholic art and cultural artifacts in England were destroyed – virtually all of them.

So English art like this in such fine condition isn’t just rare, it’s unique. It’s also an extremely early use of oil and stylistically interesting: It blends medieval forms with a wisp of International Gothic elegance and seems to presciently pre-figure Arts & Crafts decorativeness – which might hint at a missing field of art if the background decoration actually stems from illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells (that rare rose that wasn’t burned).

To really see the “Crucifixion,” I suggest you go through the entire show quickly and work your way back to it. This is for two reasons. First of all, the finishing works don’t stand up to the extraordinary level of most of the show. I don’t see why Claude Francis Barry’s 1919 morsel of pedestrian pointillism, “Victory Celebrations,” gets the back of the gorgeous catalog or the entire finishing wall.

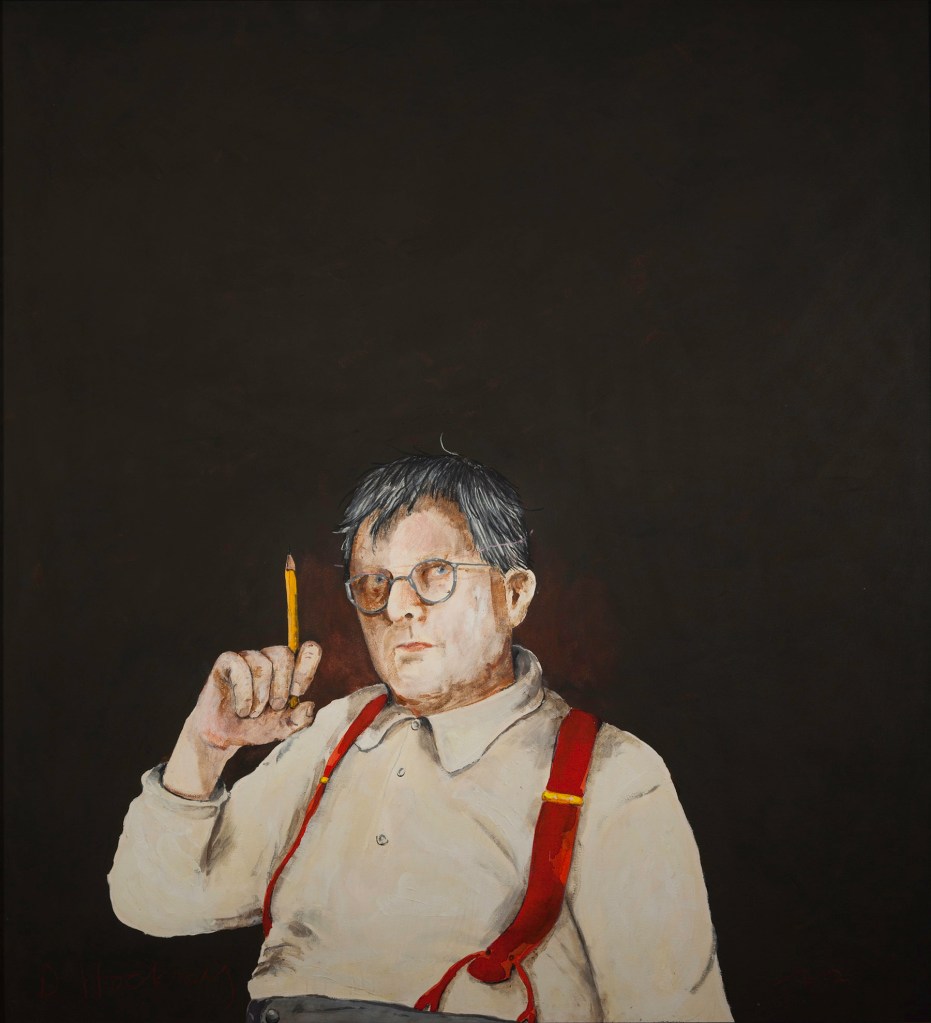

The 2002 Adam Birtwistle portrait of English painter David Hockney totally rocks (note the pink strands across Hockney’s face), but the works by Howard Hodgkin, for example, don’t fit and disappoint.

More importantly, the most profound historical and cultural insights follow a trajectory pointing back to the earliest works and the show is predictably chronological.

Here we see Henry VIII in 1513 as an awkward teen instead of a beefy spousal beheading machine. What we see less clearly was his dedication to art. (He was, for example, an avid collector of Pieter Coecke, whose amazing tapestries are the subject of a sumptuous show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

We see gentry, horses and the pompous and vain Gen. George Monck, who restored the monarchy. The big surprise in the show is a portrait of successful businesswoman Alice Barnham and her two sons, with a subtle reference in her son’s book to the bloodthirsty seductress of the Dance of the Seven Veils fame.

And even though they could put the stiff in stiff upper lip, the British certainly could paint.

It’s hard not to notice the phenomenal white streak of George Richmond’s shirt collar in his 1840 self-portrait, but the impasto black of his cravat is a stroke of genius. Alfred Munnings’ horse racers stumble on their saccharine colors, but his 1935 “Tiberius” is a horse well-painted in just a handful of strokes.

Cornelius Johnson’s 1634 portrait of a gentleman features extraordinary lace (but the ’70s called and wants its fabulous hair back).

Angelica Kauffman makes a case she earned her fame as a painter instead of as a rare woman artist: Her classicist tondo is a textbook example of technique and a round composition.

Portraits are not generally the most exciting genre, but these works from the Denver Art Museum’s Berger Collection tend to be either important or excellent, and sometimes both.

Benjamin West was born on this side of the pond, and his portrait of Queen Charlotte is particularly fascinating. The wife of George III is shown as winsome and practical. Instead of a state portrait, she is shown at her needlework. It is a beautiful and sympathetic painting.

There are important portraits by many notable artists, including Joseph Wright of Derby, Hans Holbein the Younger and Thomas Lawrence.

There are also excellent examples from among a broad range of genres: William Etty’s nude (part Boucher, part Velázquez, part steamy), John Constable’s seascape, George Stubbs’ typical horse portrait, Thomas Gainsborough’s unusual coastal scene and Adriaen Van Diest’s ambitious 1690 naval battle.

While the quality of the works and the names of the artists are impressive, what makes this show unique is how it knits back together the cultural, royal, governmental and religious context of what was the foundation of our own culture in New England, America and, more broadly, post-Enlightenment Western civilization.

British art history, after all, is our art history.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.