“Back + Forth: The Collaborative Works of Dawn Clements & Marc Leuthold” at the Bates College Museum of Art is a challenging show, and it is intended to be. The wall signage, at least when I saw the show, says little about the artists or the art other than to explain that the pair shared pieces with each other and riffed off what the other sent.

The curatorial intent seems quite clear: The public is supposed to follow the work to get their own feel for the artistic dialogue. Leuthold is a ceramic sculptor, and Clements is best known for her often large-scale brush drawings.

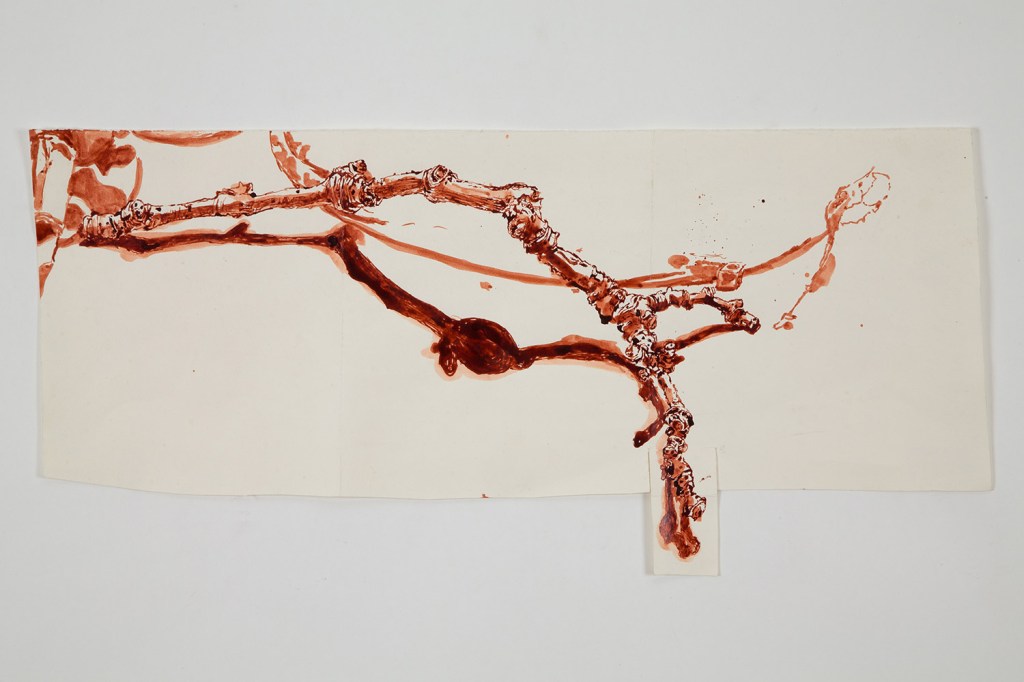

Clements’ work ranges from small, self-echoing studies to gigantic wall-sized drawings on paper. These are brush drawings in ink and watercolor. Free from bravado or preciousness, they are loose and often rough, but sophisticatedly so.

Leuthold’s striated clay disks are the strongest elements in the show, and they appear as a set form that predates the collaboration. Each of these plate-sized sculptures features hundreds of carved rivulets pointing toward the center of the disk. They shift and vary with a biological logic of living creatures. While the hardness of the glazed ceramic surfaces gives the feel of an exoskeleton (think urchins or sand dollars), more than anything else they resemble the gill-like undersides of mushrooms.

Leuthold’s other works range from basic craft forms to very loose sculpture with a particularly strong trajectory toward the rough figuration of the sculptures of Willem de Kooning or post-war European movements such as Art Brut or Art Informel. The figurative works in particular are not easy to read: The porcelain forms are rough but busy and detailed, and they tend to be colored with a single glaze (including a monochromatic chrome piece that feels like a wickedly sly reference to Jeff Koons). They are often so messy that it is challenging to parse their varied and mashed elements into portrait busts. The context of the show helps: Some of the work leans heavily toward abstraction, so it’s easy to avoid assigning representational meaning to any of the forms. On the other hand, with a wall of Clements’ drawings of people behind them, Leuthold’s wildly loose glazed ceramics come into focus almost all at once as a group, and we can see each is based on a specific drawing.

This is the core of “Back + Forth”: a conversation. Sometimes we see a drawing that clearly follows a clay sculpture, such as the clay disk and its matching drawing on the entry wall to the exhibition. At other times, we see drawings to which the ceramics respond. The result is an artistic conversation that feels like private dialogue. In other words, it feels like two people talking between themselves when what we expect in a public forum is more theatrical, like a debate or a play. In public dialogue, the speakers at least tacitly acknowledge the audience and gear their voices to the audience in a manner quite different than if the speakers were alone.

The show’s intimate quality has both positive and negative consequences. On the positive side, it feels like a genuinely honest interaction, so we’re getting an authentic look-in on a creative project. While the structure of the collaboration might seem contrived, the work certainly doesn’t. On the negative side, the work doesn’t seem made for us (other than Leuthold’s disks, and they seem to rather severely enforce this distinction rather than dissolving it), and so it leaves us outside, like we were never in on what the artists were getting at. This feels strange because curated exhibitions with multiple artists tend to welcome us on the shared points of content. Instead of dialogue in a theatrical play, “Back + Forth” feels like overhearing someone else’s private conversation in a café.

Our being left outside of the conversation brings us back again and again to this question: What are we expected to get out of the show?

As a critic, it is my initial instinct to let the work (in any and every show I visit) make its own case before I dig into the explanatory materials that accompany it. But it was surprising to read the vague explanation of “Back + Forth” on the wall (as well as in the mailer and the press release for the show) and find that the public is being left to figure out the conversation on its own. All we are told is that the artists “collaborated primarily some distance from each other.” And that raises more questions than it answers, such as: Is one of the artists teaching at Bates? Is either from Maine? In the end, it leaves the viewer with an important question: Who are these artists, and what is their collaborative conversation to us?

Although it was the second day of the show when I visited, curator Dan Mills later told me that the exhibition labeling was not complete – a point that was not communicated to me by either of the gallery attendants whom I asked about the notably sparse documentation.

The artists were easy enough to look up (though it’s highly unusual you need to). Both are New York area artists with resumes made long by numerous and important exhibitions, awards and teaching positions. Clements is represented by Pierogi 2000, one of the pioneering galleries that laid the foundation of the innovative and decidedly hip gallery scene in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood. In fact, she was featured in the 2010 Whitney Biennial – the nation’s most anticipated biennial – and this alone should pique the interest of the biennial-beleaguered Maine art audience. Leuthold is represented by George Billis Gallery. That’s the same gallery that represents Mills, who the Bates Museum director. On one hand, the Mills connection is a reminder about the extraordinary benefits of having a nationally active artist as the director of a Maine museum. On the other, it presents an appearance of conflict of interest by having Mills curate the work of his fellow George Billis Gallery artist into a show at the museum of which Mills is the director.

The missing exhibition information interrupted what would have otherwise been an effervescent art experience, and it proved particularly troubling in light of my deep respect for the Bates College Museum of Art and for Mills, whom I have lauded in this column both for his roles at Bates and for his artwork shown at George Billis Gallery.

When I spoke to Mills, I found there is no conflict: Mills germinated the Leuthold and Clements show well before he started showing with Billis. He also told me that, in the labels that had yet to be mounted, he clearly discloses his shared relationship with Leuthold to the George Billis Gallery. While all parties emerge with their integrity fully intact, an apparent conflict of interest is a serious and uncomfortable element to have left dangling, particularly when an exhibition is set up like a detective experience and the viewer is asked to step into the shoes of a critic, which, as “Back + Forth” proves, is not always a comfortable place to be.

Despite its nonplussed relationship to the audience, “Back + Forth” is an intriguing exhibition. The work is sophisticated, but we see it at a remove since the partners in dialogue address each other instead of speaking directly to the public. It acts like a game of chess, but it’s really secret theater, like the conversation during a game between two old friends who pretend they are unaware that we, the folks at the next table, are listening in.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.