Rose Marasco’s retrospective exhibition of photographs “index” is another excellent installment of the Portland Museum of Art’s “Circa” series.

A prolific photographer and the force behind USM’s photography program until she retired last year, Marasco moved to Portland in 1979. While she has created many series that swell into focus, she is not pinned down by medium, appearance or subject.

Anyone who wants to see excellent photography edited by a critical eye will be rewarded by “index.” Marasco’s formal sensibilities and abilities as a printer are top notch. Particularly with her black and white work, her feel for tones, textures and contrast is impressive.

If you prefer thematics, you will likely have a more conflicted experience. This show gravitates toward the daily life of women, but Marasco, as we see her in “index,” isn’t drawn to portraiture or personal warmth. Instead, we get artifacts with connoted contexts.

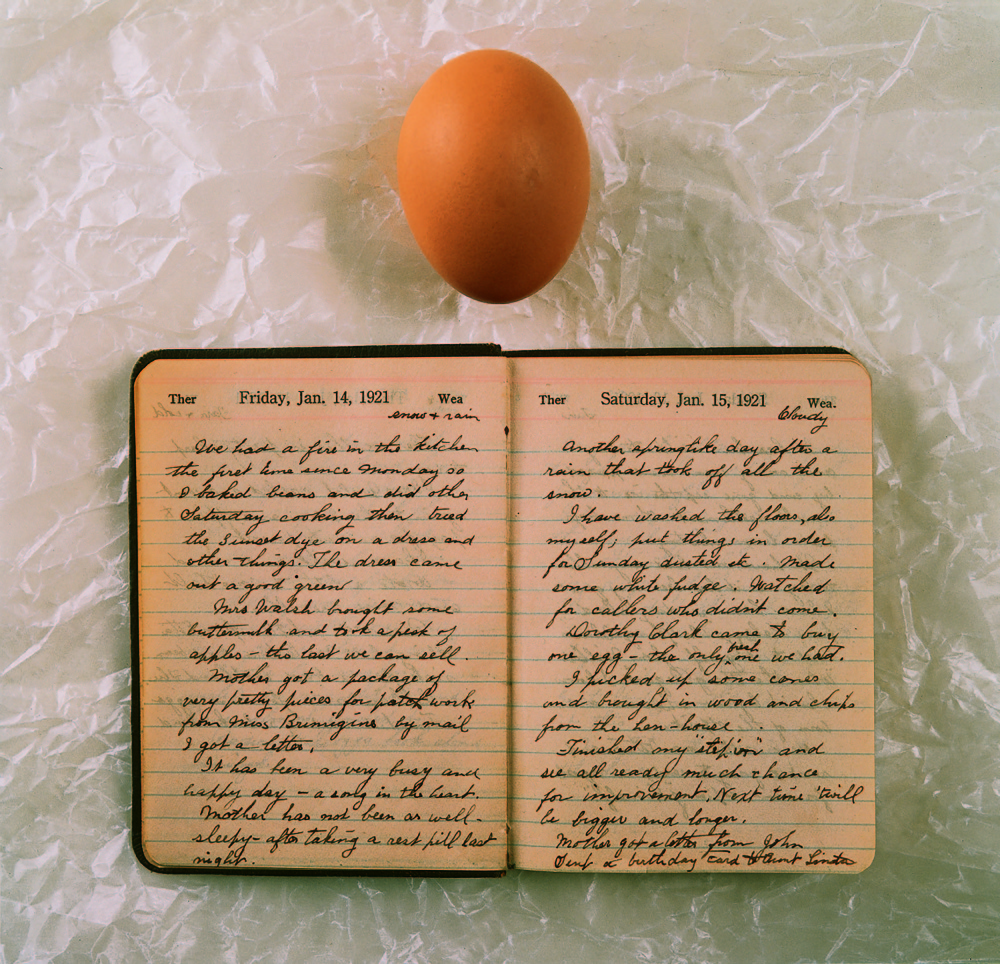

Many of the most literal works in “index” fall in this category. However, they are both satisfying as photographs and clear with their content. A group of women’s diaries shot like advertising photos is particularly satisfying and successful. The “Egg Diary,” for example, shows the old diary – splayed and legible – sitting on crumpled glassine next to an egg. The diarist discusses her daily grind – domestic chores and bartered business interactions – and concludes, “It has been a very busy and happy day.”

The diaries are fascinating, but the identifying metaphors tying them to their titles are surprisingly uncoded. The “Sink Diary” was shot in a sink. The “Popcorn Diary” is shown surrounded by popcorn, and so on.

What is happening, however, is complicated. We’re seeing excellent documentation of artifacts, but they are dressed up for theater. And this little bit of weirdness cuts to the quick of Marasco’s photographic conundrum: She is caught between photography’s “realism effect” and its potential for fictional theater.

Marasco’s strongest and largest body of photography is old-school black and white – the work we most closely associate with documentary, journalism and objectivity. But “index” also has patently theatrical work like the diaries and series of “montages” in which Marasco uses parts of different photos together to act as a single scene (or two images together to be read as a narrative). These remind us that if we accept the thesis of the realism effect, then we have to accept its complement: fiction. In other words, photography can lie.

Even ignoring the digital line Photoshopped in the sand, we all know even unaltered images can mislead. Reporting on a tornado, for example, a news station will show the single house that was smashed under the headline “Midwest devastation,” etc.

And photos were always altered: Dodging, burning, cropping, painting on negatives, touching up, multiple exposures and coloring are just a few of the tools that have always been available to professional photographers.

What Marasco is doing, however, is crashing the traditions of photography into each other. On one hand we have documentary photographers like Walker Evans, Lewis Hine and Maine’s own Berenice Abbott – objective and ethical. And then we see shots of Marasco’s own home, for example, including photographic projections on the wall and a Cindy Sherman poster showing Sherman’s “film stills” work.

In Sherman’s seminal series of photos, she would dress up to look like an actress in a recognizable narrative moment in a movie (a fiction). Later in the series, Sherman would be a fictional star in a fictional movie – leaving the audience to sense a non-existent narrative.

Marasco’s lack of method and lack of theoretical dogma work in her favor as she juggles incompatible objects. Her series of grange halls in Maine, for example, is extraordinary as a genuine documentary project – whatever you think of the granges. When we read copy about the elevated role of women in the grange system, we are being taught to think in terms of Marasco’s intentions.

By leaning heavily on the title “index” for her show, Marasco is clearly connecting her thinking to Roland Barthes – the leading semiotician (semiotics is the study of signs) regarding images. The title “index” notwithstanding, the show is run through with issues of semiotics. “Connotation,” for example, is the idea that we have to apply something we learned externally to the images; a photo of a grange hall from the street, after all, is unlikely to make an average viewer think primarily about the microeconomics of Maine farm wives. Once this issue is raised, however, we can’t easily discard Marasco’s intent.

For Barthes, there are three basic kinds of signs. An “icon” is a likeness. A “symbol” denotes its object because we have learned to make that interpretation (a green light, a red octagonal sign, etc). An “index” is a sign with a direct connection to its object: a fingerprint or smoke from a burning building.

The conflict in her show is tied to how Marasco talks about photography only as an index. Photography certainly has indexical qualities – the capturing of light reflecting off an object. But to a large extent, photography is iconic – it is a semblance of a thing rather than a direct trace of it. In the end, photography is the stuff of both smoke and mirrors.

A deeply buried theme in “index” is the uncomfortable conversation between the modes of art (as in “artifice”) and journalism with its ethical adherence to accuracy. That is not to say that Marasco’s work is problematic; rather, it’s that she is concerned with realism, fiction, theatricality, bias and cultural ethics. And within those concerns, she finds varying bodies of work that feel right to her – from her solid, early formal compositions to her more recent pinhole work in which, free of the viewfinder, she seems to find some appealing authenticity.

Authenticity matters when we consider that “realism” is simply an effect. We might look at a Richard Estes painting or a Meryl Streep film and say “how realistic!” We don’t say that about the images taken by this newspaper’s photographers – artifacts of journalism committed to specific, institutionalized ethical standards.

By titling the show “index,” Marasco appears to come down on the side of objectivity over art. Certainly her work is rigorous and dedicated to an ethic, but for the viewer, Marasco’s forays into fiction, theatricality and persuasion offer a sophisticated and compelling side of the story. It would be ironically elegant if Marasco intended the title as a fictional triumph, but while her work is tough and dense, Marasco doesn’t come across as someone who would intentionally mess with her audience.

While I don’t buy the title of the exhibition, I like the theoretical and critical issues Marasco connotes with it. And I am impressed that she’s troubled by the power of her reach.

Whatever coded or uncoded icons you find in her work, Marasco is a great photographer with gloriously subtle sensibilities. And whether you believe it or not, “index” features some great photography.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.