They are rightly called the Dark Years. From 1940 to 1944, France, with the help of the collaborationist Vichy government, was occupied by Germany. Many Frenchmen and women looked away — or helped the Nazis outright. Still others risked their lives and went underground in the Resistance movement.

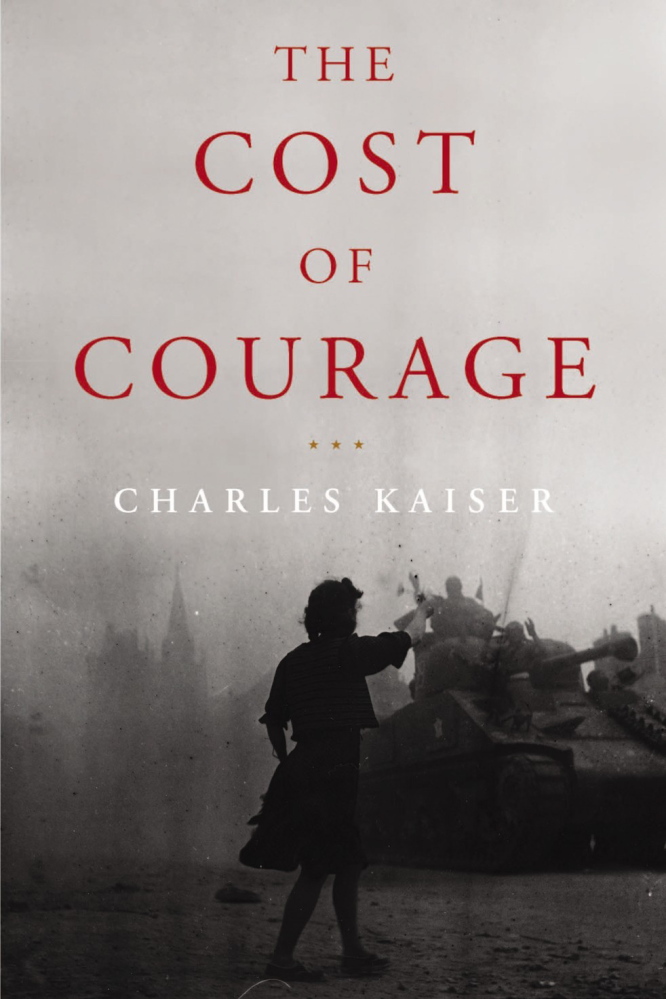

In his slim but dramatic new book, “The Cost of Courage,” journalist Charles Kaiser (“1968 in America,” “The Gay Metropolis”) tells the story of the Boulloches, an upper- middle-class Catholic family from Paris, and their harrowing experiences during the Occupation. Until now, their painful story has never been told. But Kaiser, who has known the family for decades, sensitively chronicles how this large clan responded to the calamity that befell France.

The exploits and miraculous escapes of André Boulloche take center stage in this account. A civil servant in the employ of the Department of Bridges and Highways, André took little convincing when a colleague asked him to join the Resistance in 1940, when it was barely even a movement. “Dignity is incompatible with submission,” he said of his actions. “I am a man who feels the necessity of engagement.”

André hardly had the makings of an action hero, but he proved resourceful, observing German troop movements, obtaining enemy building plans and setting up arms depots. He wrote communiqués in lemon juice, which becomes legible when heated. It was risky work; comrades were arrested, and the Gestapo came after André, too. In late 1942, he undertook a perilous journey, via Spain, to England, where he was debriefed and prepared for another mission after Charles de Gaulle, leader of the ragtag Free French forces, named him military delegate for Northern France.

Though André’s parents, Jacques and Hélène, were appalled by the Nazi occupation and the collaborationist Vichy government, they did not follow their son into the Resistance. But his younger sisters, Christiane and Jacqueline, joined in resistance efforts, distinguishing themselves with their eagerness and cool heads under pressure.

Kaiser describes the activities of the Boulloche children in an atmosphere-drenched present tense (“It is a few minutes before four on a gray Paris afternoon when a black Citroen Traction Avant pulls up in front of the drab apartment building …” ), lending the book a thriller-like quality. But it is an odd stylistic choice that jars with an otherwise conventional account of the wider war in Europe and the buildup to D-Day.

Sadly, the coming invasion could not save the Boulloches. After a comrade betrayed André in 1944, he was wounded during his arrest, deported to Auschwitz and then sent to two other camps. He survived — in itself shocking, since such an itinerary usually meant certain death. His dignity and steadfast bearing “surely saved the lives of a number of his companions,” remarked a fellow resister. “This period of his existence tempered his character — tempered it in the way one used to temper a sword in an earlier era.” H HisAndré’s parents and older brother were not so lucky. When the Gestapo came after Christiane and could not find her, officers arrested them instead. Sent to Germany, they all died in separate concentration camps.

In a brief closing section, Kaiser details the postwar life of the surviving children, who were decorated for their service. André, tormented by guilt, kept his hair shorn in a crew cut and wore a black tie every day to honor those who perished in the Occupation. He became an ardent socialist and successful politician who strove to better relations between France and Germany, who together would forge the European Union.

Some members of the extended Boulloche clan blamed the siblings for the deaths of their parents and brother. It was a painful cross to bear, and silence was one way to deal with the experience. “The only chance they had to survive was to avoid dwelling on the past,” Kaiser writes. The author also reflects on de Gaulle, who faced the immense task of uniting a nation that had been riven by collaboration and complicity with the Nazis: “The general adopted a kind of therapeutic optimism, which he considered essential to France’s recovery.” This meant papering over the uglier aspects of the Occupation.

But France, much like Boulloches, could never escape its past. “The Cost of Courage” admirably explores the dynamics of a painful reckoning.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.