With the summer season, Maine rolls out a welcome mat to the world. But it’s different than it used to be. At some point during the past few decades, the summer season switched from June through August to something more like July through September. And “season” is not the stuff of equinoxes and solstices: It’s business.

Back when summer started in June, art in Maine was a different thing. Artists came to Maine to work – not to sell. Not selling art in Maine was sort of the point. It was a place free from the machinations of the commercial New York art world. And while this partly subjugates Maine to being an art satellite of New York, that too is the point. It always was. But things are different now – and changing all the time.

A few decades ago, Ogunquit was a thriving summer artist colony. Now it’s a thriving commercial center. Last week, I made the drive from the Ogunquit Museum of American Art to an opening at the Corey Daniels Gallery in Wells. Any other time of the year, that takes 15 minutes. In season, it took an hour.

But it’s worth it. While the commercial infrastructure of the arts in Maine has built up around the state, Daniels’ approach is all about the kind of integrity we like to associate with artists: The objects and installation of his space rely completely on his eye. In turn, visitors are challenged to crank up their sensibilities and really look at the objects in the gallery. This is the inverse of typical retail settings.

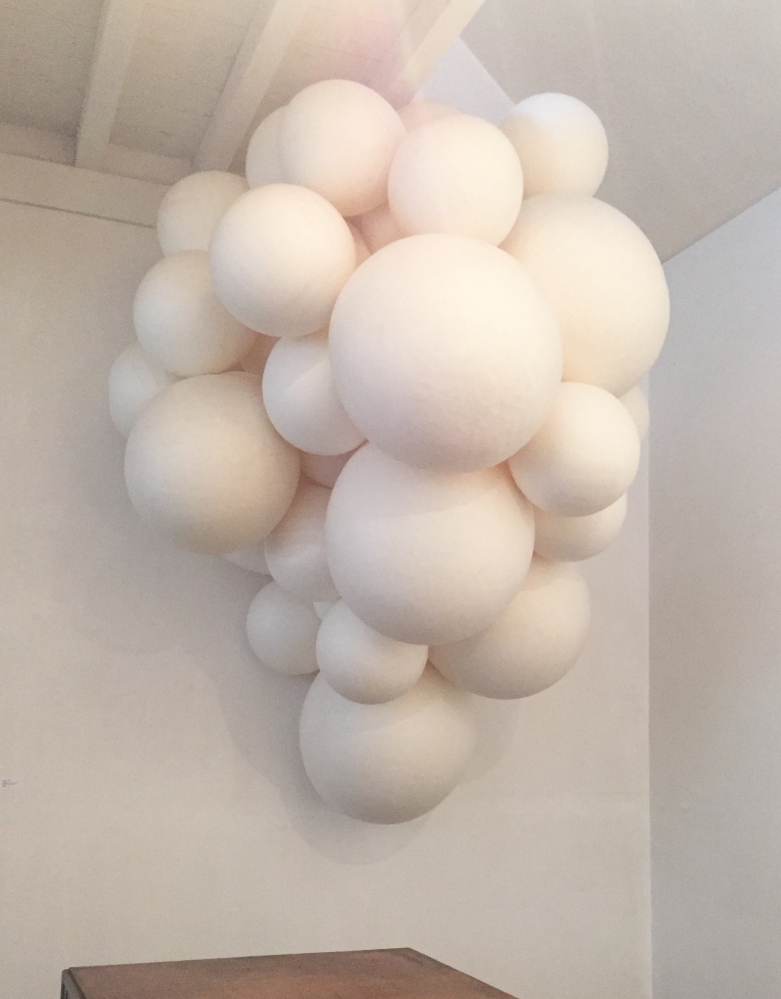

Within Daniels’ architecturally noteworthy space is an installation of 50 “hand-sculpted” paper orbs by Sarah Bouchard. Titled “Potent,” the work presents a heroically curvy feminism to counter the masculine discourse of patriarchal power. But the biomorphic logic of the varied modular forms ultimately leans away from gender and toward a biological growth model that leaves us with a dangerous sense of epidemiological potency. It is an impressive installation.

While works by most of Daniels’ artists are on view along with high-design objects and antiques installed by Daniels with a curator’s touch, the gallery has the space to mount major exhibitions of works by individual artists. It is an unusual formula for a gallery, but the combination of the minimalist aesthetic with visually rich textures is rewarding for an artist like Joshua Yurges, who is represented by no fewer than 20 works placed throughout the gallery.

Yurges’ works are paintings made of what appears to be aged, repurposed slats of wood. With their well-finished painting-as-fine-craft-object feel, Yurges is engaged in a hip conversation in which ambitious painting revisits craftsmanship, design, decoration, minimalism, process and the language of abstraction.

With his materials, Yurges also maintains dialogues with Maine artists like Jeff Kellar, whose brand of brainy minimalism is Daniels’ specialty, or the late Bernard Langlais (1921-1977), whose simple-seeming rough-wood sculptures dot the grounds of the Ogunquit Museum of American Art.

The museum is situated in a particularly beautiful coastal spot, and it features a strong collection of Maine modernists: Rockwell Kent, Marsden Hartley and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, among many others. Three current curated shows are worthy as well.

One features Civil War prints by Winslow Homer. Another features the paintings of Alfred Chadbourn (1921-1998), an under-appreciated international figure who became an important part of Maine’s culture of painting. The third, a showcase of the work of George Daniell (1911-2002), is a gorgeous installment in the museum’s Maine Photo Project series.

While Homer’s prints lack the muscular physicality and isolated individuality that made him America’s most notable painter, they reveal a great deal about his work and his audience. As a regular cover artist for the Saturday Evening Post, Homer – who famously summered nearby on Scarborough’s Prout’s Neck – had an audience beyond what any American visual artist could now command.

Moreover, his time at the front lines of America’s bloodiest war honed his journalistic eye for detail and feel for human drama.

While he brought sensibilities honed in France, New York and California, Chadbourn’s vision coincided with the June summers of Maine: recognizable coastal scenes, a plate of mussels or tourists on the beach.

What marks Chadbourn, however, is not technique but a method (centered around a set of values: light, mid and dark) that made him not only an artist of well-structured paintings, but a nationally notable author and art educator as well.

While the show features some strong paintings, such as Chadbourn’s view of Portland’s Munjoy Hill and most of his harbor scenes, the installation feels weak. The brush-luscious Chadbourn was a much better painter than you might think from a quick pass through this show.

Daniell’s black and white photographs of island life on Grand Manan and Monhegan, however, are exquisitely installed. Daniell was known for his portraits of New York celebrities; and we see this talent bubble up in the handsome shots of (buff and rather dreamy) local fishermen rather than in the largely unremarkable images of the working coast.

I was struck by label copy that revealed the Daniell show was curated by Andres Verzosa, owner of the erstwhile Aucocisco Galleries, and that works owned by the Tides Institute & Museum of Art were listed as “Purchase and gift of Andres A. Verzosa,” and others owned, for example, by the Portland Museum of Art were listed as “Gift of George Daniell and Aucocisco Galleries.”

Here, a for-profit art dealer was curating – and supplying – a show in a nonprofit museum. This is precisely the appearance of conflict discussed in a fascinating article by L. A. Times art critic Christopher Knight, titled “Museums’ disturbing transformation: relentless commercialization.”

Knight, however, diagnoses a corporate-flavored shift in museum practices (especially relations with galleries and dealers) with a brooding sense of inevitability. And while he offers no solutions, I suspect Knight has ideas but doesn’t air them in order to keep this conversation focused on the changes in museum culture. These are changes we have seen in many non-academic art museums in Maine, as more for-profit players are shaping exhibitions across the state. Knight is right: Things are different.

I have always championed art galleries in part because their mission is clear. Galleries are free to the public. They pay taxes on their transactions. Unlike museums, they sell work for the artists. Integrity is a sine qua non, but I want artists to make a living through art. I want galleries to thrive. I want people to buy art. Art, after all, is a significant – and growing –economic engine for Maine.

When I first saw the Daniell show, I was uncomfortable with the ethical complexities apparent from the label copy. But after I read Knight’s piece (with which I heartily agree), I felt differently. I was even impressed by the Daniell show label copy, because of its transparency.

My suggestion for a solution to the “relentless commercialization,” after all, is transparency. And, to their credit, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art could not have been clearer.

A healthy Maine art world just like the Maine summer: There’s nothing we need more than sunshine.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.