The latest show at Susan Maasch Fine Art is called “Four Women.” The title “Four Artists” would be more descriptive if gender didn’t matter. But it does, so we expect the exhibition to address cultural questions about gender on some level – particularly because a show titled “Four Men” would feel wrong.

Not only does it address gender, but the exhibition is all the more interesting and successful because of it.

Visually, “Four Women” is handsome. And its richness frames even the first glance into the gallery toward a wall of what are, superficially, extremely reductive and simple-seeming abstract paintings by Rose Olson.

Maasch’s curatorial conversation begins and ends with Olson’s work, so to be greeted by her subtle, high-craft abstract panels is a curatorial bit of brilliance (that disappointingly has become such a rare commodity in Portland as of late).

Olson’s monochrome abstractions on panels feature an insistent main color set into relief by a hard edge stripe or two. The stripes range from barely perceptible bands of opalescent “interference” pigments to a scorchingly solid stripe of magma-hot magenta. What takes place on center stage, however, is oddly nuanced insofar as it defies our expectations: The expansive wooden panels are glazed with scores of largely transparent layers of paint. But while a large painting will appear to us as, for example, solidly and uniformly red, the monochrome field acts like a filter – or, better, a frame – through which we are led to consider the beautiful graining patterns of the wooden panel.

This effect defies our expectations because of our history of looking to sophisticated-seeming works in the rubric of high painting rather than in terms of craftsmanship or (gasp!) craft. Monochromes, after all, are the stuff of the edgiest conceptualism from Malevich and Rodchenko to Barnet Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Frank Stella, Robert Ryman, Joseph Marioni and so on. But Olson has doubled back and taken the monochrome trail to transform the manliest frontier of painting into deliciously indulgent craft that luxuriates in the natural decorative qualities of the wood grain. Her gesture reclaims the physical object from the masculinist discourse of ownership and places it back into the shared culture of aesthetics.

Moreover, Olson’s play isn’t just a tip of the hat to Ken Noland and the big boys of post-war American painting, she knits their language into Minimalism’s (failed) critique of “post painterly abstraction.” For example, when Minimalist Donald Judd was called out for creating fictions – his reflective metal wall boxes were hollow and, therefore, revealed to be hypocritically misleading – Judd responded by making plywood boxes that made apparent every cut and screw that went into them – a literalist gesture geared to moral values such as transparency. Olson, however, is not caught up in conceptual bravado, so she is free to cross the cultural streams of craft and conceptualism.

Tilting her hat to multiple perspectives, Olson’s works emphasize the sides of their box panels. There, stripes alternate or we see the paint built up on the very edge of the support. (Getting physical, she reminds us, doesn’t have to be so masculine: Instead of John Travolta, it can be Olivia Newton John.)

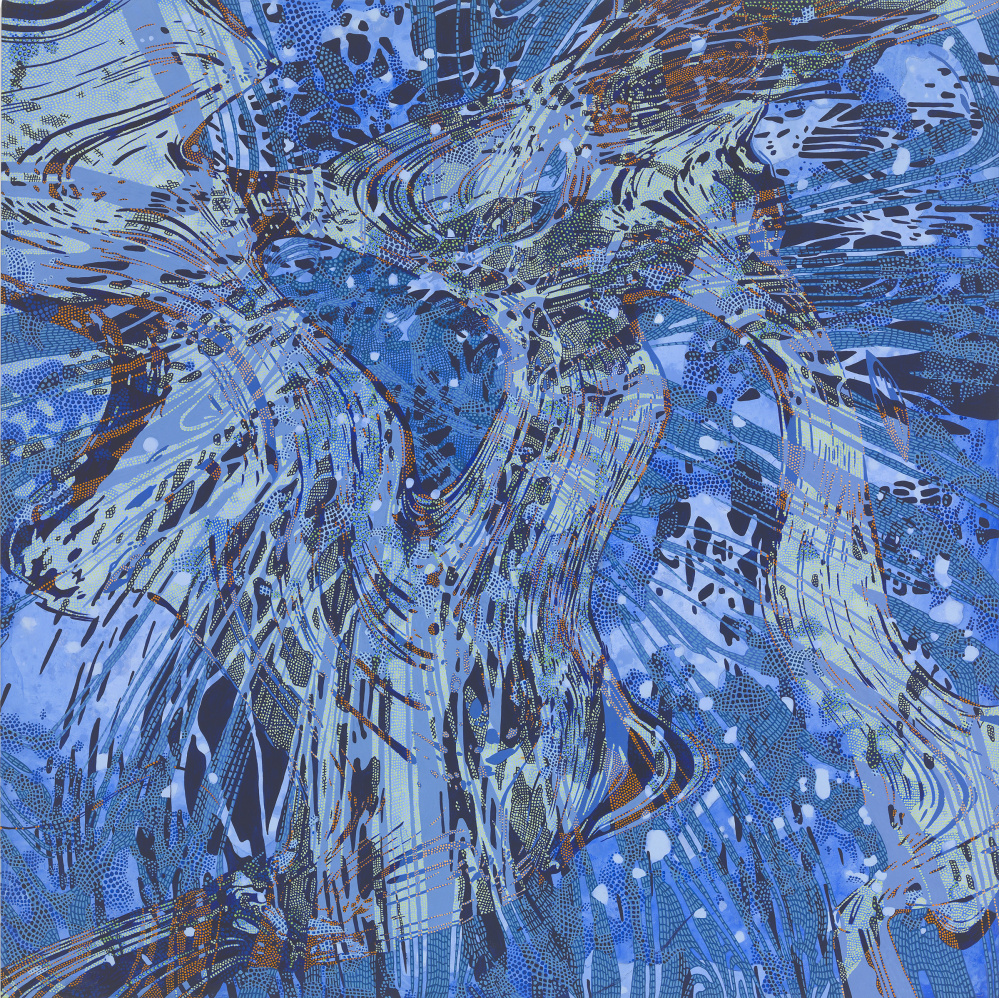

LYNDA SCHLOSBERG’S acrylic panels appear as almost the opposite of Olson’s nuanced monochromes. They are intentionally maximalist, busy and, ultimately, painterly in their tiniest details. Almost bizarrely, however, they share (and reveal) the deepest sensibilities of Olson’s insistent objects. After some time with one of Schlosberg’s paintings, the consistent systems come into focus with the lockstep logic of high-designed fabric. With this perception, the swirling forms in space are revealed to be based on rectangular grids that can be mentally re-flattened within the space of the painting – not unlike how we can mentally imagine a towel as a flat thing even when we see it twisted and bunched on the floor.

Schlosberg’s unfurling grids, in other words, remind us that the goal of Olson’s work is to announce the shape and literally flat surface of her paintings.

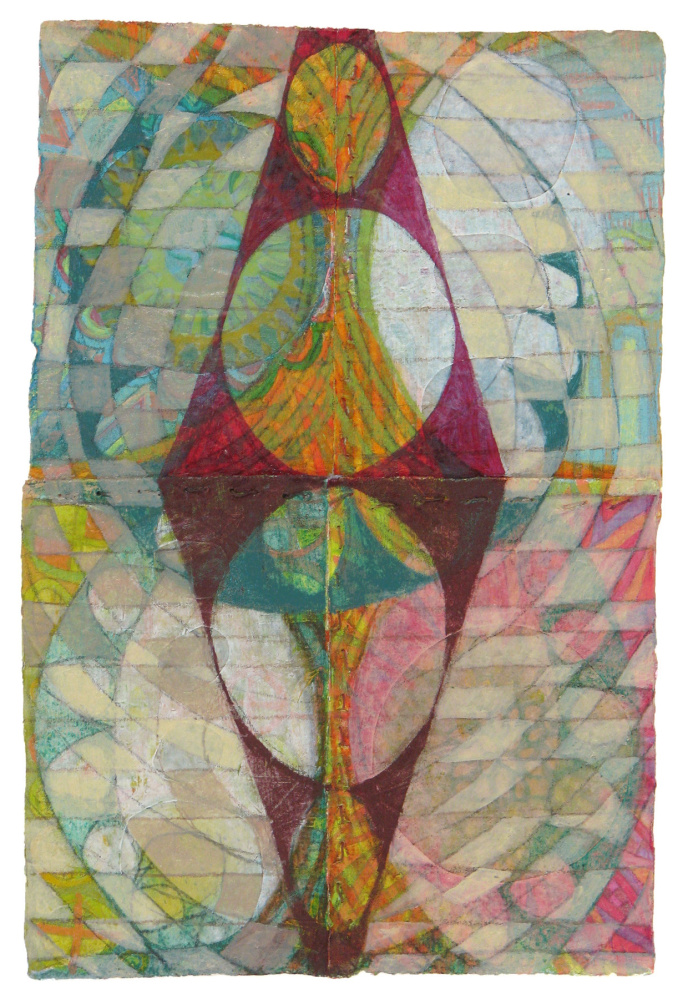

NANCY WAGNER’S colorful, Paul-Klee-like abstractions follow up on the themes of fiber and design by engaging the logic of weaving and quilting as well as the artist’s literal use of needle and thread to sew together the jangly patterned elements. Wagner’s lozenge forms feel like a compelling reiteration of the idea that Modernist collage owes something fundamental to American quilting.

JEANNE WELLS’ pleasantly grainy photographic images feel like an outlier – an idea reinforced by their occupying the least of the spaces in “Four Women.” But their subtle placement serves Maasch’s narrative well. Following Wagner’s and Schlosberg’s work, the leafy floral and fruit imagery finds its footing within a nuanced and important conversation about decoration and pattern in aesthetic productions ranging from textiles and quilting to still life painting and photography. Decoration, Wells’ work reminds us, is a thread that holds cultural aesthetics together – whether fashion, furniture, photography or fine art. From a feminist perspective, this is a constructive, positive and broadly empowering assertion.

“Four Women” is visually successful even if you don’t connect the artists to each other as part of a greater conversation. But challenging each of the artists’ work on its own terms brings them all together within a compelling curatorial narrative that is no less insightful than it is satisfying. Paintings, these women prove, can be empowered by craft.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.