CHICAGO — Alarmed by President Trump’s campaign proposals to crack down on immigration and subsequent executive orders that called for barring refugees and expediting deportations, hundreds of churches, synagogues and mosques nationwide are considering the bold move to provide sanctuary to immigrants who are living in the U.S. illegally.

“When Trump was elected, it turned into an immediate priority situation,” said the Rev. Beth Brown, pastor of Lincoln Park Presbyterian Church, the first Chicago house of worship since the election to offer immigrants who are facing deportation a place to stay. (There are now about two dozen in the Chicago area considering becoming part of the sanctuary movement.)

As the political climate shifts, immigration activists say the nature of the sanctuary movement could change. Though federal authorities say they will continue to avoid raiding hospitals, schools and houses of worship, activists fear that sacred spaces could become targets under the new administration. Historically aimed at changing policies through public campaigns and protest, the sanctuary movement could be forced underground.

Last week, a mother of four with two misdemeanor convictions sought sanctuary in the basement of a Denver church after authorities denied her request for a stay of deportation. How her case plays out could determine how congregations play a role going forward.

LOVING THY NEIGHBOR

“It’s about people committing to trying to keep the person safe and out of custody,” Brown said. “If it’s under the radar, if that’s what people are saying is going to save somebody’s life or keep someone from being separated from their family, we’d follow that guidance.”

The idea of sanctuary goes back centuries. Greeks and Romans offered limited protections to criminals who sought shelter in temples. From the fourth to 17th centuries, English law granted immunity to fugitives as long as they were inside a church.

The more contemporary approach to sanctuary as a political movement in the U.S. first unfolded in the 1980s. Drawing from sacred texts that teach loving thy neighbor and welcoming the stranger, churches and synagogues opened their doors to immigrants fleeing civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala.

In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld conspiracy convictions of several sanctuary ministers. But the same court also cleared the way for many of the Central American immigrants who were living in churches to seek asylum, which was hailed as a victory.

The movement resurfaced when deportations began to rise dramatically during the Bush and Obama administrations.

In 2006, Elvira Arellano, a former maintenance worker at O’Hare International Airport, took refuge with her 7-year-old son inside Adalberto United Methodist Church in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood. Arrested four years earlier as part of a post-9/11 sweep of immigrants who were in the U.S. illegally and working at airports, Arellano became the face of the new sanctuary movement.

The targeted immigration enforcement tactics “go against the grain of what our faith traditions teach us,” said the Rev. Noel Andersen of the New York-based Church World Service, which tracks the sanctuary movement. “We believe that we have a higher calling and that we should respond to a higher law.”

A 2011 memo from the director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement further empowered the sanctuary movement. Federal agents were instructed to avoid “sensitive locations” including hospitals, schools and houses of worship unless there is an imminent risk.

According to Andersen, 250 congregations nationwide signed up to help shield immigrants after raids in 2014. Roundups in 2016 prompted more than 100 more to support the sanctuary movement. Now 800 congregations have stepped up to provide relief, he said.

“Certainly there’s more risk involved, and the fact that people are still so interested says a lot,” he added.

Gail Montenegro, a spokeswoman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement under the Department of Homeland Security, said agents are still expected to abide by the 2011 directive.

“DHS is committed to ensuring that people seeking to participate in activities or utilize services provided at any sensitive location are free to do so without fear or hesitation,” she said in a statement.

SAFE PLACE FOR THE VULNERABLE

Andersen said people aren’t just afraid of immigration enforcement. They also worry that political rhetoric might make legal immigrants more susceptible to discrimination, hate crimes or profiling by law enforcement.

“What we understand sanctuary to be is expanding, and it is expanding beyond the world of just undocumented immigrants,” Andersen said. “We want to be a safe space or refuge for anybody who is vulnerable or targeted under this administration.”

Andersen said most of the congregations that sign up for the movement agree to offer support for individuals in sanctuary – providing security, preparing meals, distributing fliers or organizing prayer vigils.

Only 13 churches in the U.S. have housed individuals, including University Church in Hyde Park. Of the 20 deportation cases that relied on sanctuary since 2014, five are still pending in the courts, Andersen said, including the case of a Bolingbrook father of five who sought sanctuary at University Church in April. For most cases, invoking sanctuary is a public declaration. But some sanctuary seekers negotiate with authorities privately while residing within the walls of the church.

Leaders at Lake Street Church in Evanston said the congregation has elected to become a sanctuary church, but citing uncertainty about the political climate, declined to say whether anyone ever moved in.

Shanti Elliott, the church’s immigration justice leader, said “The public nature is very important to sanctuary. On the other hand, a decision to declare sanctuary in solidarity with immigrants, who are very vulnerable and may be at risk, carries with that a commitment to protect them.”

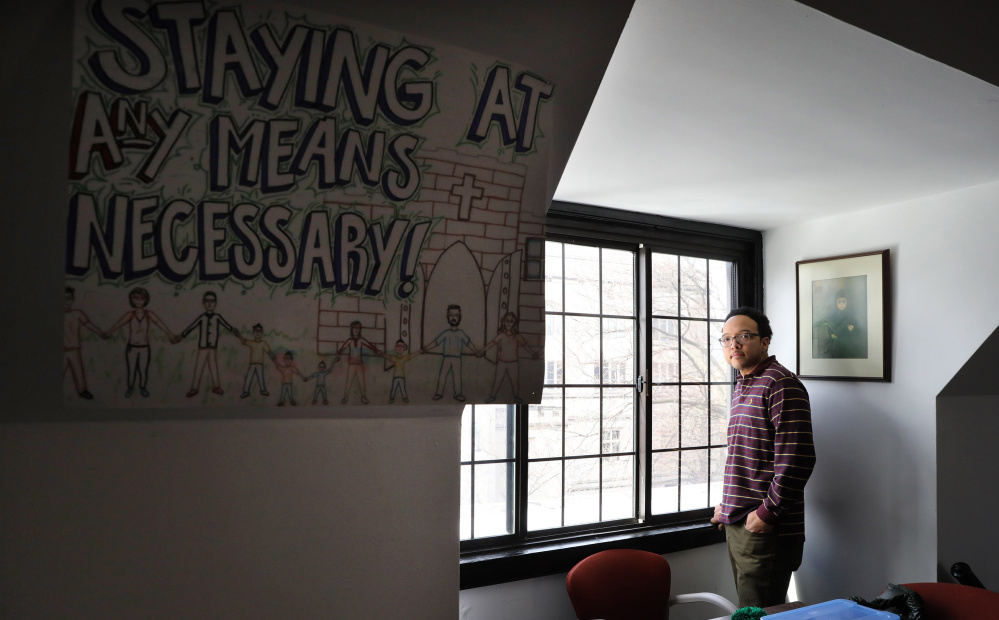

After invoking sanctuary in April, the Rev. Julian DeShazier, pastor of University Church, said he started spotting unmarked cars parked on the streets around the church. Volunteers accompany a person living inside the church 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“It’s a security measure for him traveling from one room to the next,” DeShazier said. “It’s not to watch him but to watch those who are watching him.”

That said, the protocol at University Church when there is someone in sanctuary is to not stand in the way if authorities show up and present the proper warrants.

“That becomes obstruction of justice,” he said. “We’re trying to obstruct what we believe is injustice.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.