PORTLAND — Andy Graham grabbed a camera and headed over to Kennedy Park to shoot a few pictures.

The year was 1975, and Graham was a 23-year-old student at what was then the University of Maine Portland-Gorham. Camera in hand, he attracted the children around Kennedy Park and the lower end of Munjoy Hill like a magnet.

Graham, the founder of Portland Color, looked anew at those images recently, and was taken by what he saw.

“I discovered a sweetness in the people I had not anticipated seeing. There was this humanness I hadn’t remembered,” he says.

Graham’s photographs revealed a specific time and place that somehow felt vastly different from the Portland that we know today. The urban renewal projects of the 1960s had stripped the city of much of its glorious past, and the gentrification of the Old Port had not yet begun.

Portland in the ’70s was still sleeping. It was caught in between its heralded history and a promising future. In the age of Watergate, disco and bellbottoms, the city was being reborn and redefined, and its personality as a hip and trendy city by the sea had not yet taken hold.

Graham wondered, “Who else was shooting photos back then, and what do their images look like?”

The answer to that question forms the basis of a new exhibition, “Seeing Portland – 1970 to 1984,” which opens this week and remains on view through May 1 at Zero Station, 222 Anderson St., Portland.

The exhibition feels like a family photo album. We laugh at the fashions, revel in the memories and remark at how much has changed.

The exhibition brings together the work of several accomplished photographers. In addition to Graham, photographers with work in the show include Tom Brennan, C.C. Church, Rose Marasco, Joe Muir, Mark Rockwood, Jeff Stevensen, Jay York and Todd Webb. Graham curated the exhibition, along with Anne Riesenberg, his wife; and Keith Fitzgerald, who runs Zero Station.

For Riesenberg, looking at these images unleashes a flood of memories of a city that many of us will hardly recognize, of a time that feels far more distant than it actually is, of innocence and of youth.

‘IT HAS SOMETHING TO DO WITH YOU’

For folks who weren’t around Portland back then, this exhibition might feel something like the stories your grandfather used to tell about what it was like to be young. “Perhaps you can’t quite grasp what they mean, but deep in your bones you know it has something to do with you,” Riesenberg writes in her curator’s statement.

The photos, she says, document Portland as it was, and opens up our common history like a box of treasures. “Savor them and you savor what has come before, catching a glimpse of the mechanisms of memory as they build up and become the past,” she writes.

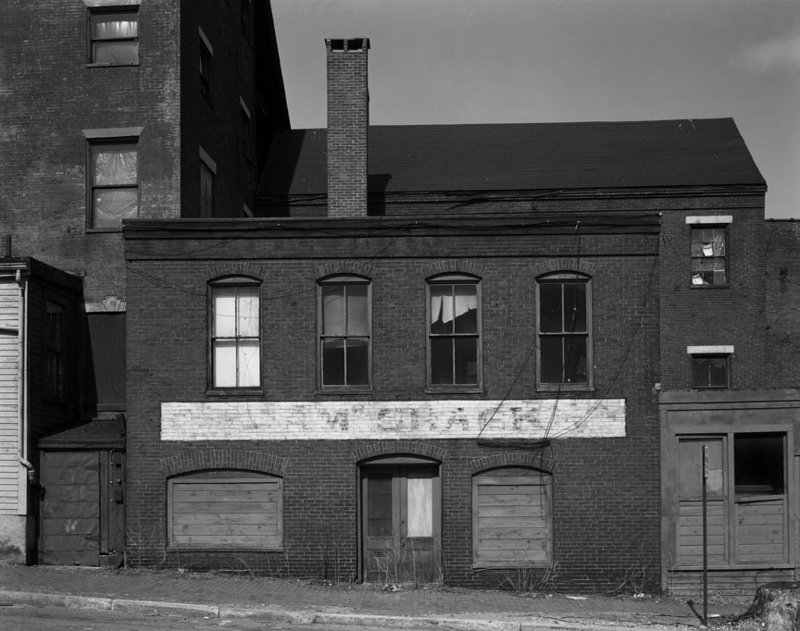

Graham’s original hope for this show was to rely on the photographs of nationally known artists who worked in Portland at that time. He knew that Webb, who died in central Maine in 2000 after an illustrious career, spent considerable time in Portland in the 1970s. His work in this exhibition reveals a city that looks trapped in a time warp. He has images of popular restaurants of the day – Sid’s, the Pagoda and Splendid Restaurant – and some fine examples of architectural photographs.

But aside from Webb, Graham came up empty in his search for the nationally famous. So instead, he set his sights on folks who were young at the time, lurking in the city and experimenting with photography.

Graham was astounded with the amount of material that he found.

For the most part, the photographers with work in this show were fresh out of school. They had abundant enthusiasm, endless energy and a commitment to photography that in hindsight has proven both laudatory and historic. Collectively, their photographs capture the city’s architecture, its people and its pulse.

‘UNDISCOVERED TREASURE’

Graham characterized Church as “the undiscovered treasure of Portland. He deserves an entire show. In the same way that other great artists of Maine are being discovered, Chris needs to be rediscovered and assessed as an important person in the art world. One of my hopes for this show is that Chris will get the recognition he deserves as an extraordinary photographer.”

Church was 26 years old in 1970 when he moved into a studio on Monument Square.

“Portland was my inspiration. Portland was my subject,” he said in a phone interview. “When I went out and about, I was doing mostly buildings around the area on the peninsula. If I went farther afield, I did landscapes.

“But in the city, I found old buildings and things that caught my eye. From my perspective, they were very beautiful. I wanted to record them. I wasn’t necessarily documenting the city. But after 40 years, they become a document of sorts. But I was more interested in creating art.”

He still is. Church is doing pretty much the same thing today. Back then, he used a 4-by-5 viewfinder. He still does, but he has followed the evolution of photography from film to digital.

Stevensen, a Portland photographer, focused his camera on the old waterfront of the early 1980s. He used an 8-by-10 view camera, which lends itself to a rigorous approach to composition.

“My approach to this subject matter was documentary and more, to infuse my personal vision into the project,” he writes in his statement. “The choice of where to point my camera conformed to no purely historical hierarchy. I photographed that which struck my eye, and assumed that the totality of my photographs would convey the larger truth of the subject.”

Marasco moved to Pine Street in the West End in 1979. She has moved since – but only about a block away. That neighborhood has been home for a long time, but back then, everything was new. Her photographs offer the perspective of a newcomer who is delighted with her surroundings.

“When I wasn’t teaching, I walked the street photographing – first on the Western Prom, and then into the West End neighborhoods. I came home to my makeshift dark room and went to work,” she writes.

In the darkroom, Marasco joined two photos into one, creating a montage. Several examples of her experiments are in this show, including one that combines both the Western and Eastern proms.

In 1982, she wrote of her work, “The perception of reality is more about what one brings to it than what is there. The making of photographs is more about what one takes from it than what is there.”

Today, Marasco is still struck by the notion of perception and the way memory is linked and informs our perceptions. Although she has matured as a photographer over the years, the themes that she began exploring all those years ago are present today.

As he was curating this show, Graham said he remembered a phrase, “the old weird America,” made famous by the critic Greil Marcus.

These images, he said, remind him of “the old weird Portland, when Portland was eccentric. This show is about those remnants. My hope is that the photographers who are working now will look at the city with the same warmth and exacting vision that these photographers employed in the 1970s.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story