Monhegan is a lithic wonder. Less accessible than other pictorial icons, it has been less abused by painters. It submits itself as a bastion in a restless sea and as an exemplar of man against an often furious nature.

Still, when reduced to canvas, those qualities, as forceful as they are, are anticipated and thus often diminished. We expect painters to provide them.

Kevin Beers’ views of that staunch place are less expected. He sees Monhegan as a place of radiant vistas. The season can be winter or summer, but the former is the feature of a show of his work at Gleason Fine Art in Boothbay Harbor.

In those months, cleared land bulges up against the horizon and seeks the companionship of what has been built upon it. It is man and nature in concert, but not in the softened tones of summer. Their union is expressed with icy clarity.

I direct you particularly to “Icy Bogdanove House.” In it, the house and the land are in retreat from a remorselessly cold winter sun. The light is freezing, and the season becomes compellingly beautiful.

This is a very good show.

REFINEMENT MULTIPLIED

I recommend July Salon at June Fitzpatrick at MECA. I am tempted to say that here the show is the thing. It isn’t, but there are times when the work of multiple artists is so contributory to one another and the installation is so much a distillate of their views that an aesthetic enchantment forms.

This is so pronounced in this show that I am prompted to suggest that it be boxed up — gallery and all — and shipped to a big museum. If you are responsive to refinement, logic and technical finesse, this is as good as can be had here.

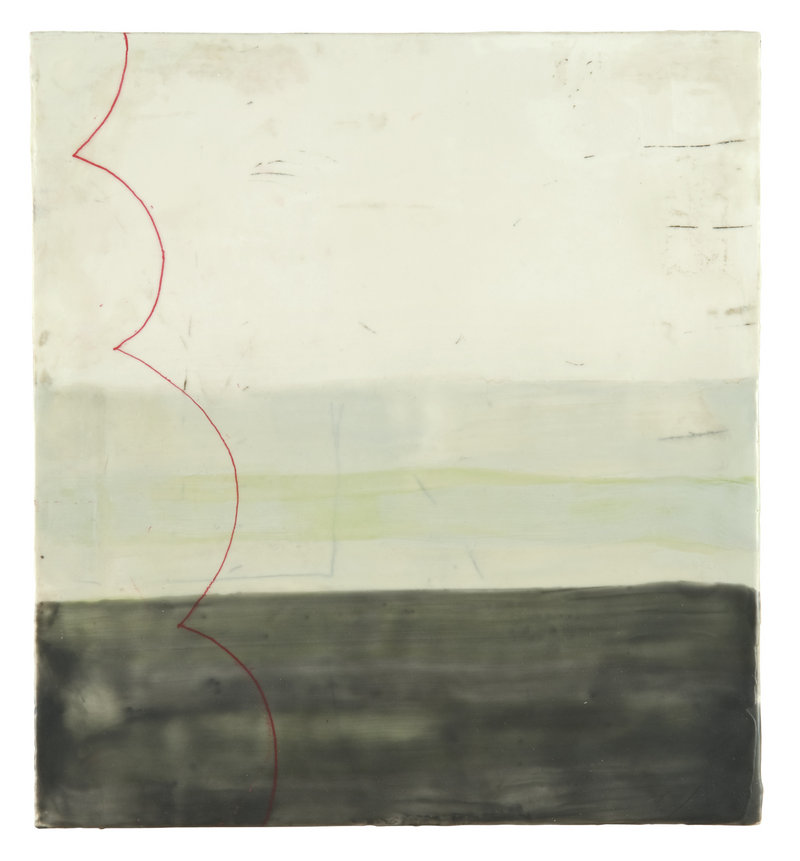

Lynda Litchfield’s encaustics caught my early attention. She has shown work in that medium for some time, but not with the force of those in this show. The holding back that gave her efforts a tentative quality has abated. Here, she slams into the wax with aesthetic muscle.

There is an emergent geometry in the work and a becoming nod to early Greg Parker. I pass Parker as an established grand master and note the continuing development of Noa Warren. His work is acquiring a sophistication that belies the earliness of his professional years.

I’ve known Larry Hayden as a draftsman of Ingresque achievement, but here he has become a loaded-brush Sumi ink linear abstractionist. His work is now measured in feet, not inches; it pulls you in to create a protective environment.

Noriko Sakanishi has reduced the scale of her exquisite graphite and pigment ink drawings. The reduction creates a chaste personal relationship with the viewer. The perfection of the work, its modesty and intensity of purpose are unmatched.

Duane Paluska’s painted canvasses are evolving from gestural — if that can be said of linear abstraction — to formal bilateral symmetry. That grounds his work; it gives it a position and for the most part advances it.

Joanne Mattera is the colorist in this show. Her eye has an in-your-face assurance that is almost shocking. It is a pleasure to behold, as are the two elegant inks on paper by Joe Kievitt.

COURAGE IN SCULPTURE

My response to Tom Chapin’s sculpture at ICON Contemporary Art is partly visceral, more emotional perhaps than intellectual. Anything in wood has an advantage over, say, stone or bronze. It is organic, never quite dies and is a part of our own lives.

But Chapin, in this show, is not a carver. He reduces wood into elongated forms, but does not extract form from the block. He combines elemental shapes into groups that are often unbalanced in their proportions to create series of spatial tensions.

He may derive from Constantin Brancusi — a carpenter turned architect and sculptor — in his election of shapes, but essentially there is a fusion between organic and elemental forms to produce an independent expression. The manner in which the fusion is achieved is a visceral pleasure.

One can see it best in “No Direction Home,” a large piece in wenge topped by a marble cap. Perhaps that cap is the core from which the long wenge extensions grow, but I think of this piece as architectonic — a feat in unbalanced engineering — and thus a precarious challenge to the conclusions of Isaac Newton. It keeps me on edge. So does “Black Cloud,” a construction of small rectangular mahogany forms, engineered to describe a sweeping arc. It too is never at rest.

This is a fascinating show of work achieved with a courageous eye.

FOCUS ON THE FORM

And now to George Lloyd’s “Selected Works on Paper” at the George Marshall Store Gallery in York. Lloyd is among the foremost artists in our midst. And this show is among the best he has had.

As its title implies, it is made up of certain works on paper. Although not billed as a retrospective, it draws upon work completed in Berkeley in the 1970s, work from Santa Barbara and from Connecticut of the 1980s, and from the present in Maine. Though not comprehensive, it is a record of both continuity and growth.

The structural impulse is always present — more derived from Cubism in the earliest work, looser and distinctly West Coast light formalism later on. Finely introduced lines of structure restrain the principal images — generally the human figure — even though some of the lines appear as simple annotations.

They are not that; they are directions to the viewer to stay away from the edges of the sheet and focus on the principal form. They ensure the fact that the whole will be an entity of the parts. They are part of a continual striving for integration.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 45 years. He can be contacted at: pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story