WARREN — If there is one thing Albert Paul knows, it’s how to do time.

He’s been in and out of prison – mostly in – since he was 18 years old. He turns 80 this June.

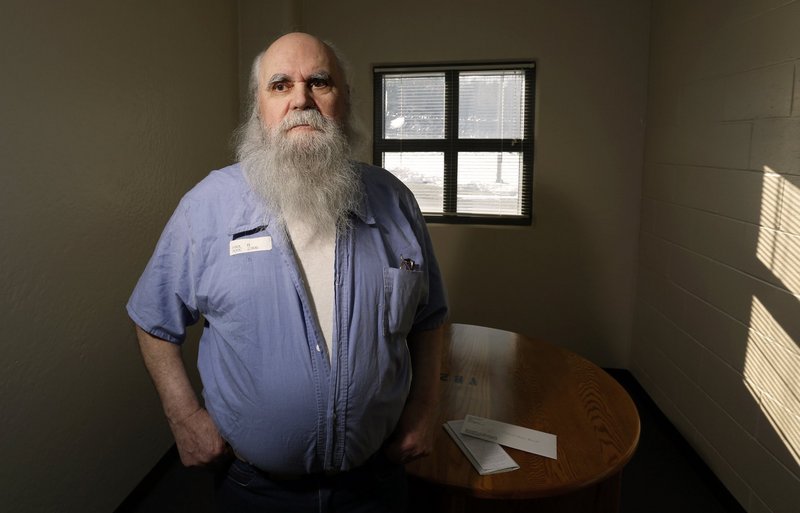

He is both the oldest and longest-serving prisoner in Maine, and he likely will die in his cell.

There was a time when nearly all of his energy was spent trying to break free from captivity. He escaped four times from either prisons or mental hospitals and had several more near-escapes, including one that rivaled a climactic scene in a Hollywood movie.

But Paul hasn’t tried to escape for decades. He says he’s still cunning enough to pull it off; he just doesn’t have the fire. He’s accepted his fate.

Besides, he has nowhere to go.

“The world out there has changed for me. It’s a foreign place,” Paul said during an interview at the Maine State Prison in Warren.

Paul’s story may be extreme, but he represents an aging prison population that, in some ways, mirrors the state’s population shift overall. In 2005 the number of prisoners age 50 or older was 9 percent. Now, it’s 16.5 percent. The number of inmates over the age of 60 has doubled in that time.

There is a cost to letting inmates grow old. The Maine Department of Corrections estimated that it has spent nearly $1.5 million since the early 1950s to keep Paul locked up.

So, what happens to a man who grows old in prison? How does he pass the time? How does he reconcile a squandered life?

Paul’s only real memories are the crimes he committed: a series of ill-fated robberies in his late teens and 20s; a pair of brazen prison escapes in the 1960s; the murder of a stranger in 1971 that sent him to prison for life, a crime to which he confessed at trial but says now he didn’t commit.

He continued to cause trouble even behind bars, sending a bomb to a former prosecutor and trying to escape several times.

For the last three decades, though, Paul has been a forgotten criminal.

His secret to an incarcerated life has been keeping to himself, tuning out all the “prison scuttlebutt,” and, believe it or not, having a positive outlook.

There is one more thing, though. Paul has left the outside world behind completely.

“I’m here doing life,” he said. “My life is here. I can’t get involved with the outside.

“There’s two worlds: free world and prison world, you know? I don’t want people visiting me saying, ‘Oh, we was down at the beach over the weekend.’ I don’t want to hear that kind of talk. I can’t go to the beach. You see?”

Until he agreed to an interview, Paul had not had a visitor in 13 years.

FOSTER HOMES, THEN CRIMES DATING TO 1951

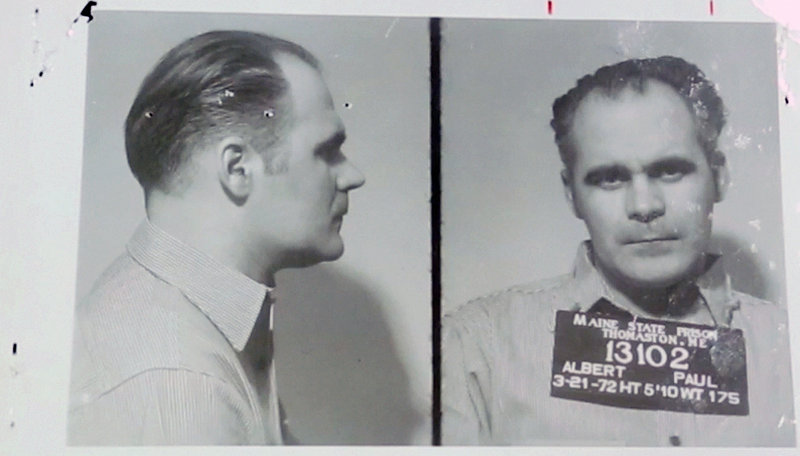

His hair, once coal black, is entirely gray and flows almost to his shoulders. His beard is gray, too, and nearly as long. His belly sticks out over his prison pants. He favors his right leg when he walks. When he speaks, his voice has remnants of a French-Canadian heritage.

He was born Albert Joseph Paul on June 17, 1933, at the height of the Great Depression. He has no memory of his mother, who died of stomach cancer when he was 3.

Paul spent the next six years with five sets of foster parents. In the worst family, Paul often went without food, taking nearly rotten potatoes out of a pig’s trough and sneaking downstairs in the middle of the night to steal slices of bread.

He remembers running away from one home – his first escape. He was returned the next day.

When he was 9, his father came down from Montreal to fetch him. They spent the next several years in Canada, where his father worked as a watchman in a glass factory. Paul dropped out of school. When he wasn’t in the local bakery learning to stretch dough, he was getting into trouble.

By the time he returned to Maine as a teenager, his thievery skills were well-honed.

The archives of the Portland Press Herald document Paul’s crimes dating back to 1951, depicting a brash thief who always got caught.

In 1951, he robbed a cabdriver with a gun he stole from a Sanford home, along with two watches, a camera and a telescope. The next year, he hid overnight inside a Portland post office, waited until sunup, and then surprised the blind owner of a newsstand and stole $200, two cartons of cigarettes and three pocketknives.

In 1953, he was caught on the roof of a Portland building after attempting a jewelry store heist with another man.

In 1956, he held up a grocery store in Brunswick for $12, a crime that earned him a five-to-10-year stretch from a judge who hoped the lengthy sentence would make an impression.

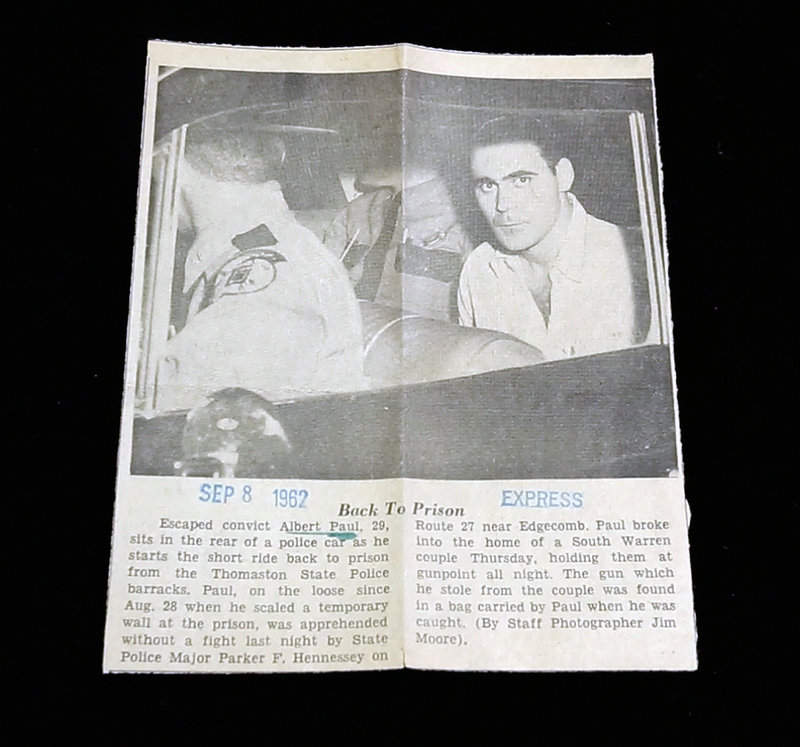

In the 1960s, Paul escaped twice from the former Maine State Prison in Thomaston. The first time, he left a dough mixer running, slipped away from the kitchen and scaled a 16-foot temporary wall. He was free for 11 days and spent part of his time holding an elderly couple captive in their home with their gun.

In the second escape, he tricked the guards by throwing a shoe over the wall and then hiding out in an upholstery shop until the search efforts slowed. He climbed the wall again but had nowhere to go. He turned himself in within 24 hours.

CONFESSION LEADS TO LIFE SENTENCE

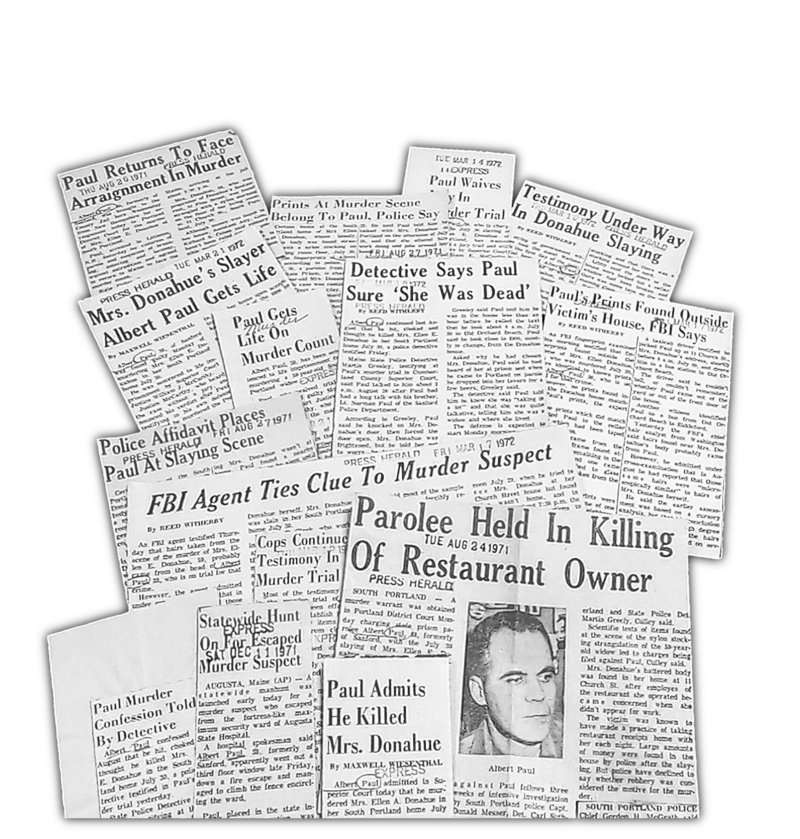

In July 1971, Ellen Donahue was found dead in a pool of her own blood at her South Portland home, beaten and strangled.

Detectives discovered fingerprints outside and hair samples inside. They talked to three of Donahue’s neighbors, who saw a man at her home the day before she was found. They found a taxi driver who picked up a man at Donahue’s address hours before police declared it a crime scene.

Everything pointed to Paul, who had been released from prison on parole only months earlier.

At the murder trial in March 1972, Assistant Attorney General Peter Culley built his case around the fingerprints and hair samples, which matched Paul’s, and the witnesses, who all testified that Paul was the man they saw at Donahue’s home.

Paul’s attorney – a young defense lawyer named Daniel Lilley – did something unusual in a murder case: He called the defendant to the stand, where he proceeded to confess to Donahue’s murder in painstaking detail, according to the trial transcript.

Paul testified that he had heard about Donahue in prison, heard that she was a widow and tavern owner who was known to take her cash receipts home for deposit in the bank the next day.

He testified that he went to her house and waited for her to come home. As she got ready for bed, Paul emerged from a closet with a knife. Donahue said she could give him only a hundred dollars.

When he went into the kitchen to get water and think about her offer, Donahue tried to attack him with a wooden tray. Paul grabbed the tray and shoved her against the stone fireplace. Her head began to bleed, and she started to scream.

Paul said he put his hands around her throat to quiet her.

“I choked her quicker than I realized,” he told the jury.

The hope in confessing was that the judge might show clemency and convict Paul of manslaughter, a crime of passion, rather than murder, a crime of premeditation.

It didn’t work.

“I think the defense is asking me to set a legal basis for the requirement of submission on the part of a robbery victim that would excuse violent acts,” Justice William McCarthy said. “Unfortunately, this I cannot accept, nor do I feel that is the law.”

Paul had waived a jury trial, putting his fate in the judge’s hands. He was found guilty and sentenced to prison, at hard labor, for the rest of his life.

CHANGING HIS STORY PUBLICLY

Today, Paul says he made up almost all of the confession. This is the first time he’s publicly told what he says is the real story.

He did go to Donahue’s home intending to rob her, he said, but had an accomplice, a man named Alfred Pelletier. It was Pelletier who killed the woman, he said.

Paul said that the cellar window with his fingerprints on it was too narrow for him to fit through, but Pelletier was much smaller and could fit. That’s why none of Paul’s fingerprints were found inside, he said.

Pelletier, as it turns out, is dead now. Attempts to find information about Alfred Pelletier in Maine were unsuccessful. A man by that name died in 2011 in Madawaska.

So why did Paul confess?

“He was a friend of mine. I wasn’t going to put the finger on him. What could I do?” Paul said, matter-of-factly.

Former prosecutor Culley, now a partner at Pierce Atwood in Portland, said he remembers the murder case as “pretty straightforward” and Paul as a “terribly pathetic guy.”

“I always got the sense that (Paul) wanted to be in prison. I don’t think he knew how to function on the outside,” he said.

Culley said he doesn’t recall anything during the trial to suggest Paul had help in the murder.

Lilley, who has defended more than 50 murder suspects since, said he doesn’t remember much about the case. Even if he did, though, his conversations with Paul are still protected by attorney-client privilege.

Paul never appealed the conviction, which is unusual in murder cases. He said he saw no need.

Besides, he said, “I always figured I could escape.”

ESCAPE ATTEMPT PREDATES MOVIE SCENE

In 1974, Paul was spending a lot of time in the prison craft room where inmates could make things to be sold in the prison showroom and keep part of the proceeds. Paul specialized in miniature wooden cradles for dolls. The tiny furniture proved popular, but it also gave him an idea.

Paul amassed a list of enemies over the years and wanted to have a little fun with one of them. He fashioned a makeshift bomb out of match heads and light bulbs, hid the contraption underneath one of his cradles, and sent the cradle to Robert Marden, a Waterville attorney who prosecuted Paul in a robbery case two decades before. Marden received the package but never opened it. The bomb didn’t go off.

Paul, whose name was on the package’s return label, said he wanted to get caught. His theory: Do something crazy and they would send him to the mental hospital, where he could escape more easily.

He was sent to solitary instead. He decided to escape anyway.

Paul discovered one day that the concrete floor of his cell could be broken with a little effort and some help from a smuggled pry bar. Beneath the crumbled stone was earth.

He dug a few feet down, into an unused sewage drainage pipe that had filled over time with loose dirt.

Each night, he arranged pillows in the shape of a body beneath a blanket on his narrow mattress, climbed under the bed frame and began to dig. He put the dirt in pillowcases and then emptied them in an unoccupied cell nearby when no one was looking.

In a little more than a month, Paul had tunneled 42 feet from his cell to the edge of the prison’s foundation, 8 feet from freedom.

But the foundation of the prison was built with massive granite blocks. He couldn’t go through them, even with his smuggled tools. He couldn’t dig around them either because they were connected. He thought about digging up from the spot where he stopped, but he feared that the tunnel might collapse and bury him alive. He had to give up.

The escape attempt mirrors a scene in the 1994 movie “The Shawshank Redemption,” based on a novella by Stephen King. In the climactic scene, a wrongfully accused prisoner crawls through a tunnel he dug from his cell to the prison’s inner wall and then escapes by breaking a hole in the sewage pipe and crawling through it to freedom.

Asked whether Paul’s attempt might have been the real-life inspiration for the story, King, who lives in Bangor, chuckled and said he had never heard of Paul.

RELATIONSHIP DOESN’T END WELL

In 1979, Barbara Jeannie Hecker came into the prison shop in Maine and bought a doll cradle for her then 9-year-old daughter.

The girl wanted to write a letter to the person who made it – Albert Paul.

So she did. Hecker started writing, too. She and Paul formed a relationship, first through letters, then visits. Paul would sometimes send her money that he earned from prison work.

The visits ended years later when Paul was transferred to Pennsylvania.

Hecker died of lung cancer in January at age 72. Her daughter, Kathleen Fickett, is now 42 and lives in Lewiston. Fickett said she hadn’t thought about Paul in 30 years but still remembers the effect he had on her family.

She remembers driving from Maine to Illinois – another state where Paul was once an inmate – with her mother to visit him in prison there.

Her mother had developed complicated feelings for Paul during a rough patch with her husband. In many ways, Fickett said, Paul was the opposite of her father.

“He was an imposing figure,” she said. “I was intimidated.”

The relationship didn’t end well. Hecker was trying to rebuild her fractured marriage, and Paul was an impediment. He sent threatening letters after Hecker stopped visiting. Fickett remembers her mother being frightened of Paul, even though he was locked up, because he had escaped before.

Fickett was surprised to hear that Paul was still alive.

“He was so good with his hands. His woodwork was beautiful,” Fickett said, remembering the long-gone doll cradle. “It’s sad that he never tapped into something more positive in his life.”

ON THE LAM FOR TWO WEEKS

Paul was just shy of his 49th birthday and was doing time in a federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pa., when he breathed free air for the last time.

Assigned to a metal shop, he often moved around the prison. One day he noticed that when guards came around to count the inmates, he wasn’t always where he was supposed to be, but they counted him anyway. In another section of the prison where Paul made his regular rounds, boxes were stacked on a truck, filled with towels and other linens to be cleaned at a nearby building outside the prison wall.

Paul knew he couldn’t fit in one of the boxes, but he could fit into three of them if they were connected.

When the guard came around one morning in 1982 and marked Paul as present, he actually was in the boxes. By the next check, the truck was gone and so was Paul.

He was out of prison for two full weeks. He went to Minnesota and robbed a bank.

“They don’t give you escape money at the prison,” he said with a wink.

He made his way back East but never reached Maine. Police picked him up after he broke into a home in Rotterdam, N.Y. He didn’t bother putting up a fight.

After the escape, the Pennsylvania penitentiary didn’t want Paul anymore, so the Maine State Prison took him back.

Authorities never even bothered to file additional charges – he was already serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

LIVING IN A BATHROOM-SIZED CELL

Since the late 1980s, Paul has bounced among prisons in several other states, including Florida and Illinois. He joked that he’s seen more of the country as a prisoner than he might have as a free man.

He came back to Maine in 2008 for good and has been quiet since.

He had 11 siblings once, but they’re all dead now. Their lives are reminders of what his could have been.

One brother, Harvey Paul of Biddeford, died in September. Harvey and his wife were married as long as Albert has been a prisoner. Harvey Paul had 10 children, 22 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren who all called him “Pops.” Another brother, Norman Paul of Sanford, was a police officer and deputy chief who became a state lawmaker. He died in June 2010.

These days, Paul spends 90 percent of his time inside a bathroom-sized cell.

A single-frame bunk crowds one wall. Two bookshelves hang above a sink and toilet attached to the second. The third has a narrow window that doesn’t open and has no view. The fourth wall is bars.

He said he stays away from junk food at the canteen.

He has high blood pressure and occasional chest pain for which he takes medication but otherwise is healthy.

“I’d like to live to be 100,” he said. “If I do, I’ll invite you back.”

There is little to remind Paul of the world outside or of his past, and he seems at peace with that.

One word is crudely tattooed across the knuckles of his left hand: “Antipas.”

It’s the last name of an inmate whom Paul served time with back in the 1950s, someone he called a true friend.

But “Antipas” was also a character in the Bible’s Book of Revelation, the story of the Apocalypse that ends the New Testament.

He is described as a contemporary of John the Apostle, a faithful witness of Jesus Christ and a martyr who lived in Pergamos, an area where many believe the devil presided.

Before he was sentenced to death for refusing to denounce Jesus, Antipas was asked, “Don’t you know that the whole world is against you?”

Antipas replied, “Then I am against the whole world.”

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story