Regional School Unit 23 had a rocky marriage right from the start.

For more than two years, the three member communities in York County were gripped by an emotional debate about local control, finances and the future of the district.

In the end, Saco and Dayton each decided to go it alone. Old Orchard Beach is now the sole member of RSU 23, a misnomer that stands as a reminder of the communities’ failed attempt to share resources and cut administrative costs under Maine’s sweeping 2007 school consolidation law.

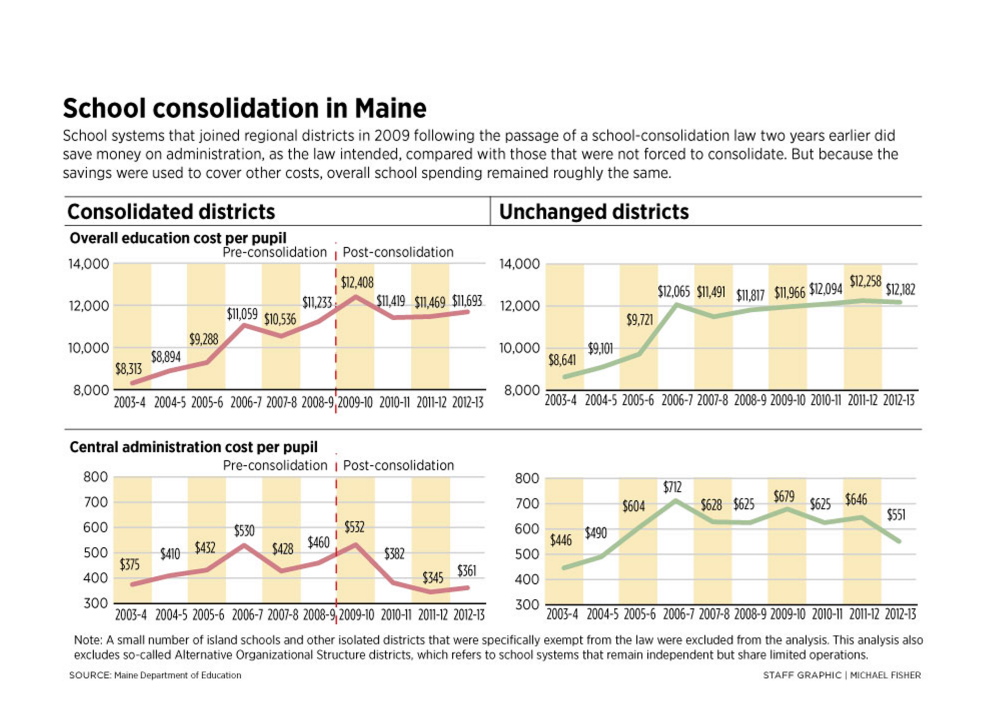

An analysis by the Maine Sunday Telegram five years after the law took effect found that combined districts did achieve modest administrative savings, but that the average district did not reduce overall spending or pass savings along to taxpayers.

“If we could join and provide common services and save money and improve education, why not? The concept was logical,” former Saco Mayor Ron Michaud said of the school reorganization law. “Its implementation was a total failure. It divided communities up and down the state and saved minimal money.”

Former Gov. John Baldacci’s watershed school consolidation law was designed to reduce administrative costs by creating larger, more efficient school districts and to equalize and improve educational opportunities for students across the state. In some cases it did, and the majority of the 127 communities that merged to comply with the law has so far stuck with the 24 new multitown school districts created in 2009.

However, more than 30 communities have at least formally considered leaving their new districts. Nine have already gone through the lengthy divorce process and 10 more are scheduled to vote on withdrawal in November, including Freeport, Windsor and six of the eight towns in Belfast-based RSU 20.

The Telegram analyzed education spending trends and interviewed those directly involved to assess whether the law is failing or working. The analysis found:

• Most consolidated districts did reduce the costs of central administration, such as superintendents and their staffs. While not dramatically slashed, system administration costs per pupil dropped 12 percent in the average consolidated district over the past four years compared to the previous four years. That compares to a 3 percent reduction in districts unchanged by the law.

• The average consolidated district used the savings from combined administration to cover other costs, such as expanding classroom programs or protecting services from state funding cuts. Average spending in consolidated districts has grown to more than $11,400 per pupil, a level higher than preconsolidation spending. While some say freeing up administrative spending for education was a key goal of the law, others say the failure to provide tangible tax relief in many districts added to the sense of disappointment about the mergers.

• Political tensions – not financial factors – have been the primary reasons behind the breakups of newly created regional school districts. A desire to restore local control over budgets and school operations has doomed a number of arranged marriages.

• Despite the high-profile quarrels and breakups, however, most of the communities that merged remain together. For some, the law forced collaboration that has benefited schools and taxpayers. Also, many of the towns that are leaving consolidated districts are joining others that are seen as better fits for their communities.

“It’s hard to get at the question of whether these are successful,” said Education Commissioner Jim Rier. “I would argue there are many that are working well, but there are some municipalities that are not happy with how things have been working.”

PITCHING CONSOLIDATION

The idea of school consolidation was controversial from the start. While Baldacci and other supporters said having fewer school districts would improve educational opportunities and save money by increasing efficiency, many others questioned how forcing districts together would accomplish those goals.

Baldacci said his consolidation proposal came at a time when the state was facing significant funding gaps in health and education, which made up about 80 percent of the state budget. The administration also recognized that many districts had declining enrollments but were top-heavy with superintendents. For example, there were 17 superintendents in Aroostook County serving the same number of students as a single superintendent in Portland, he said.

“We were growing in the wrong areas. It needed to be addressed,” Baldacci said. “We had to look at things that were going to make us more administratively efficient without undermining local control.”

But the issue of local control was always a sticking point for districts considering consolidation, especially in more rural areas where schools are an integral part of the town’s identity, said Janet Fairman, a University of Maine professor and co-author of two studies on school reorganization in Maine.

“Overwhelmingly, the concern was to have local control over the state (education) subsidy and to keep local schools open,” she said. “It’s a sense of identity for our small towns in Maine. When they have a regional school system, they begin to feel like their small town is losing its own identity.”

While local control emerged early on as a barrier to consolidation and continues to be the reason most towns leave consolidated districts, the threat of penalties also raised the ire of some local officials. Many people who would later lead withdrawal efforts said all along that they only voted to form consolidated units because of the threat of penalties. Districts that did not consolidate could have faced hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost state aid, though penalties were delayed until 2010-11 and eliminated in 2012-13.

Some were also skeptical of the savings the Baldacci administration said were likely.

“I just didn’t think the savings people were talking about would be there,” said Skip Greenlaw of Stonington, who serves on the local school board and led the unsuccessful 2009 effort to repeal the consolidation law. “I thought the idea of trying to force marriages between school units by using penalties was the wrong attitude.”

Bill Webster, former superintendent of RSU 24 in the Ellsworth area, said the threat of penalties was at the forefront of discussions in many communities considering consolidation.

“There’s no question that part of the motivation for some to vote in favor of reorganization was because of the penalties that would be imposed for those that did not consolidate,” he said.

Fairman said some resistance by local officials and educators to consolidation may have come from how the policy was rolled out and its emphasis on penalties for districts that did not consolidate.

“Sometimes policy has to include carrots and sticks. This one was heavy on the sticks,” she said. “In a way, the mandate to consolidate may have been a little heavy-handed, both because it didn’t give school districts options for doing this in a more voluntary way and didn’t provide for more flexible ways of doing this.”

TRIMMING DOWN THE DISTRICTS

The consolidation mandate started with a goal of winnowing Maine’s 290 districts down to 80. Districts with 2,500 or more students didn’t have to consolidate, nor did island schools and some other districts that were given exemptions. That meant the initiative became focused mainly on small, rural districts. In 2009, the number of school districts dropped from 290 to 227, far short of the original goal.

The intent of the consolidation law was twofold, but much of the focus as the plan was rolled out was placed on the fiscal benefits of reducing the number of school districts and, ultimately, the amount of money spent on administrative costs.

Baldacci said at the time that consolidating 290 districts to fewer than 80 – the original goal – could cut $36.5 million from the state’s 2008-09 budget.

Finding new partners and combining operations were not the only challenges facing school districts at the time. During the recession, federal stimulus money was given to schools but the money was a one-time bonus, not a long-term fix, leaving superintendents looking for other ways to pay. State aid to education was also cut and, more recently, there were cuts to municipal revenue sharing.

“If there were supposed to be cost savings, they didn’t materialize or at least didn’t materialize quickly,” said Eric Conrad, spokesman for the Maine Municipal Association. “That $80 million loss (in municipal revenue sharing) is the number one thing driving up local property taxes, not school consolidation.”

Newly consolidated districts reduced spending on central office administration, including superintendents, by an average of 12 percent in the four years after consolidation, according to an analysis of education spending in the past decade.

The consolidated districts spent an annual average of $405 per pupil in central administrative costs in the four years after consolidation, compared to $462 spent per pupil per year in the four years before consolidation.

Maine school districts that were unchanged by the state law saw their administrative costs drop on average by 3 percent, a trend that may be the result of tightening budgets and less state education funding. Those districts spent an annual average of $625 per pupil on central administration in the past four years, compared to $642 per pupil in the four years before the consolidation law took effect.

Rier, the education commissioner, said there were – and continue to be – savings in many of the consolidated districts. Those savings may not have been passed on directly to taxpayers because the money was instead used to equalize or improve education across the districts, the other intent of the law.

Overall per pupil spending by consolidated districts increased an average of 12 percent in the four years after the consolidation, although that is largely because of a large increase in 2009-10 that may have been related to transitional costs. Per pupil spending has stabilized and remained below the 2009-10 levels in the past three years.

Meanwhile, overall per pupil spending in districts that were not affected by the consolidation law increased 8 percent in the past four years compared to the preceding four years.

In RSU 16 in Mechanic Falls, Minot and Poland, the school budget was reduced from $21.8 million in 2007 to $18.2 million in 2009. But Superintendent Tina Meserve said passing savings along to taxpayers is not necessarily typical of consolidated districts.

“It’s probably pretty unusual five years later to have a budget $1 million less than before consolidation,” she said.

Regional School Unit 10 in Rumford saved more than $800,000 by combining central offices and special education programs. In RSU 23, about $200,000 in administrative costs was trimmed from the district’s first budget, but that money was used to expand gifted and talented programs and add all-day kindergarten across the district.

Webster, the former superintendent of RSU 24 and current head of the Lewiston School Department, said RSU 24 saved in excess of $1 million in 2009-10, but that money was largely used to mitigate what would have been higher increases in local property taxes. He said the savings came primarily from combining administration, appointing one nutrition manager to oversee all district cafeterias, and on supplies because the district, which now serves Ellsworth and eight other communities, had greater purchasing power.

“While we saved a lot of money, for the local taxpayer it may not have seemed like RSU 24 saved money because taxes were either flat or going up,” he said.

POLITICS OF LOCAL CONTROL

Ask those who have closely followed the consolidation process about the driving force behind withdrawals and they’ll cite the same factor: local control.

“In my opinion, it’s all about control,” Rier said. “In some cases, they say the cost is higher, but I really believe the core reasoning behind the withdrawals that occur is because the unit trying to withdraw wants more control over their school and students.”

Consider RSU 20 in the Belfast area.

The consolidation of those communities into one district has led to some talk of combining two high schools, one on each side of the Passagassawakeag River and both with room to spare.

It’s the kind of savings opportunities that the law was intended to exploit. But it’s also the kind of issue that sparks dissent and a desire for more local control.

The high school in Searsport is less than half full and the high school in Belfast is 69 percent full. The cost of educating one student in the smaller school in Searsport is more than twice the cost at the larger school in Belfast, which could accommodate all Searsport high school students.

But that would be complicated and the board leading the consolidated district isn’t considering it. Instead, six of the eight member towns will vote in November on whether to withdraw.

“Mainers aren’t good at being forced to do things,” said Kristin Collins, a Belfast city attorney who has coordinated withdrawal efforts with its partnering towns. “When you’re in that environment – the forced marriage environment – you’re never going to start with a lot of love.”

Michaud, the former Saco mayor, said his city only joined RSU 23 because the city stood to lose close to $500,000 in state funding if it did not. He saw some sense in the idea, but was irked that communities across the state felt forced to create partnerships instead of letting them develop naturally with neighbors.

From the beginning of the union in 2009, there was tension in the district, largely from Saco residents who questioned the fairness of the cost-sharing formula and how additional local contributions to the education budget were being spent, especially on school repair projects.

“I discovered that we were paying a large portion of the additional local (share) but those costs were not coming from our community,” Michaud said.

What developed during the first two years of RSU 23 was an “us-versus-them” mentality among some in the communities, leading to talk of Saco leaving the district. When school officials started telling Saco families that their students could attend less-crowded Old Orchard Beach schools, the withdrawal talk intensified and voters ultimately supported exploring how to leave. Dayton residents followed suit.

In separate votes in November 2013, Saco and Dayton chose to leave RSU 23. Saco now operates as an individual school unit. Dayton decided to share central office administration with Biddeford, but has its own school board.

In Cumberland County’s RSU 5, frustrations with its relationships with partner towns have prompted Freeport’s vote Nov. 4 on whether to divorce from the district it formed in 2009 with Durham and Pownal.

Tension about maintaining local control of the Freeport schools peaked in June 2013, when a $17 million bond to renovate the overcrowded and outdated Freeport High School failed by a thin margin. A majority of Freeport voters approved the project, but the referendum’s ultimate failure was driven largely by voters in Pownal and Durham concerned about property tax increases to pay for the project.

Webster, the former superintendent of RSU 24, said the process to form that district in 2009 was long and arduous. The process brought together 12 communities that had previously belonged to six separate school districts, he said. There was tension nearly from the beginning of the union.

“Irrespective of the savings and educational improvements, there were and are a number of active community members that, regardless of cost, wanted local control over their own elementary school. People were elected to the school board with the sole mission to make that happen,” he said. “I could see the writing on the wall. I didn’t want to spent 75 percent of my time on politics instead of education,” Webster said.

Webster left the district three years ago to lead the single-community school department in Lewiston. Ellsworth, Hancock and Lamoine left RSU 24 earlier this year.

EQUALIZING EDUCATION

Baldacci said one of his main goals with the school consolidation law was to improve and equalize educational opportunities across the state.

“I think there are examples of districts that never really got on board,” he said of the withdrawing communities. “But there are times you see districts that embraced the change and it worked.”

Fairman, who co-authored a 2013 study on the impact of consolidation on educational opportunities, said research showed school reorganization did seem to work when it came to expanding and equalizing opportunities for students across the district.

“Our research did not show a tremendous cost savings. One of the main reasons was districts that chose to consolidate then chose to use those savings to expand or improve educational programs for students,” she said.

Of the 24 regional school units Fairman studied, all but two reported making changes to the delivery or content of educational programs. Three-quarters of the districts reported improved educational opportunities for students that were directly linked to consolidation.

Fairman said school districts reported improving education by expanding technology and gifted and talented programs, adding or expanding prekindergarten and all-day kindergarten programs, aligning special education services and increasing professional development opportunities.

WITHDRAWALS EXPECTED TO SUBSIDE

If all of the communities voting Nov. 4 decide to pull out of their RSUs, 15 percent of the towns forced to merge in 2009 will have withdrawn.

The flurry of withdrawals was not unexpected by education officials, who say the districts couldn’t consider the move until they had been together for three years. They also say the tide of withdrawals is not expected to last.

Rier said even before consolidation there was a way for school districts to break apart when things weren’t working, and there may be occasional situations where towns seek new arrangements. He is quick to point out there are 350 towns that belong to one of the state’s 75 multitown units – including those that predate the law – so it’s a relatively small number of communities leaving districts to go it alone.

“Some of that interest in withdrawal had built up over the first two or three years of these units being together,” Rier said. “The same thing happened with (school administrative districts), which were always allowed to withdraw.”

And Rier also wants people to understand that not all towns leaving their first RSU are shying away from multitown units altogether, proof, he believes, that there is success to be found in consolidated districts. Starks and Frankfort left regional school units only to join different ones. If voters in Belfast, Belmont, Morrill, Searsmont and Swanville decide Nov. 4 to leave RSU 20, they will form their own consolidated unit.

Fairman, the UMaine professor, said she believes more studies are needed that evaluate the effectiveness of consolidation, both financially and academically. Despite a lack of analysis, anecdotal stories from around the state have led her to believe that many school systems will remain consolidated because they have found fiscal savings.

“Many superintendents and educators acknowledge that students have more opportunities in larger systems, especially at the high school level,” Fairman said. “I can’t foresee where we’re headed, but it appears we’re going to continue to move into an era where school districts collaborate voluntarily to control and reduce their costs.”

Just as it is hard to evaluate how consolidated units have worked, it is too soon to tell if communities that left RSUs are better off on their own, Rier said.

“It remains to be seen how well it plays out for regaining that (local) control, controlling costs and how they meet the needs of their students,” he said.

Kennebec Journal Staff Writer Michael Shepherd contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story