LEWISTON — Fatuma Hussein, a Somali immigrant who came to Maine more than a decade ago, says domestic violence among immigrants and refugees is too often relegated to silence.

“The challenge we have in the immigrant and refugee community is that we don’t acknowledge it,” she said this week. “In my culture, people say we don’t have it, or they say, ‘So what?’ ”

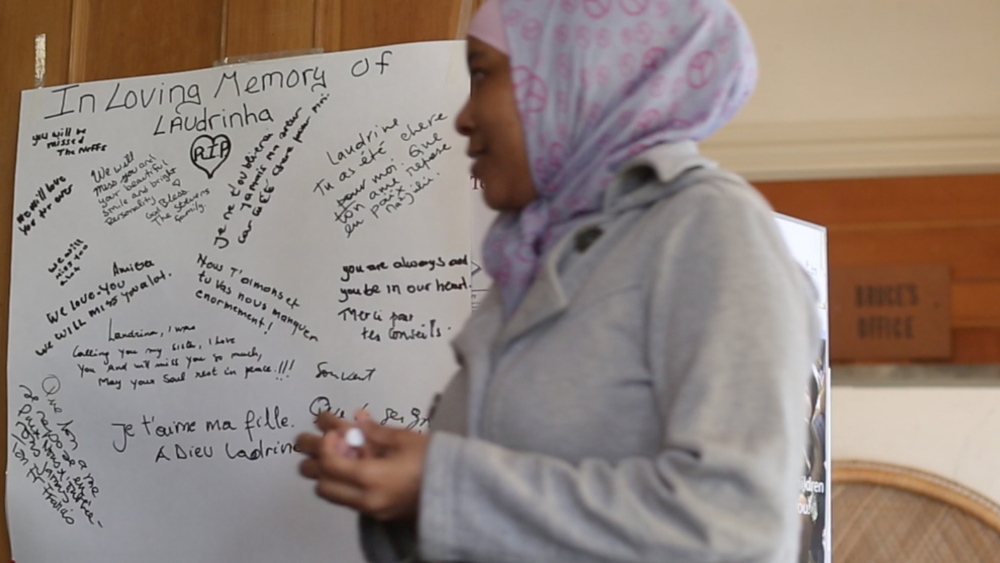

Hussein’s organization, United Somali Women for Maine, is dedicated to educating immigrants and refugees about domestic violence. The hardest part is persuading victims to break their silence, a reality she was reminded of last week when Laudrinha Kubeloso, a refugee from Angola, was killed.

Days before she was run down in broad daylight on a Lewiston street, Kubeloso confided in close friends that she feared her ex-fiance might try to harm her, even kill her.

Evaristo Deus was infuriated after she called off their engagement because, according to friends, she caught him in a relationship with another woman.

But Kubeloso, who was four months pregnant when she was killed, never went to police to report her fears or seek a protection from abuse order. None of her friends reported any suspected abuse, either.

It wasn’t until after Kubeloso was killed that Lewiston police even heard Deus’ name.

“We can’t do anything if we don’t know about it,” said Lt. Michael McGonagle.

Kubeloso’s silence is not unusual in Maine’s growing immigrant and refugee community, according to domestic violence advocates and others who work closely with the population.

Immigrants or refugees often don’t want to risk shame in their community by reporting abuse, or risk having to carve out a new life if a partner ends up in jail. They don’t understand that police officers can be trusted, and sometimes don’t even realize that domestic violence is a crime.

“You are asking women to go against their very culture,” said Jane Morrison, executive director of Safe Voices, a domestic violence shelter and outreach organization in Lewiston. “It’s an enormous challenge.”

Maine has seen a steady influx of immigrants, mostly from African countries, over the past decade. A study by the Migration Policy Institute of Washington, D.C., last year showed that Maine’s foreign-born population has grown by nearly 17 percent in the past 11 years.

Many immigrants have settled in Lewiston and Portland, the state’s two biggest cities, where there already are established immigrant populations and better access to social services.

Lewiston and Portland police officials said they don’t track domestic violence calls or arrests by race or immigration status, but agreed that reports of domestic violence by immigrants or refugees seem to be rare.

Desiree Michaud, domestic violence coordinator for the Lewiston Police Department, works closely with the immigrant community and said more work needs to be done.

“If they see me and become familiar with me and recognize that I’m someone to be trusted, that’s the biggest thing,” she said.

LAWS DIFFER IN HOME COUNTRIES

Immigrants or refugees often come to Maine from countries racked by poverty, violence and corruption, where laws – and how they are enforced – differ greatly from those here.

Kubeloso, 32, and Deus, 33, hailed from Angola, a country in southwest Africa mired in civil war for decades. Both sought asylum in Lewiston.

Adriana Joao, who also is Angolan, said Kubeloso had been happy since arriving in the United States last year.

“She has a chance here,” Joao said.

But Joao also said Deus became controlling, telling Kubeloso what to do and what not to do. She told her friend to contact police, but Kubeloso never did.

Last Tuesday, as she walked home from an adult education class, Kubeloso was struck from behind by a vehicle with such force that the impact tore her clothes. She was taken to a local hospital, but neither she nor her fetus survived.

Deus was arrested a day later at a New York airport as he tried to flee the country. He now faces murder charges in Maine.

Matthew Perry, assistant director of prevention services at Family Crisis Services in Portland, which serves immigrants and refugees, said Kubeloso’s silence is not unusual.

“It’s hard enough for American women to ask for help,” he said. “But then you add this whole cultural layer.”

Karen Wentworth, also of Family Crisis Services, said, “What is considered acceptable behavior here is very different (from their home country).”

It wasn’t until 2011 that Angola adopted laws that made domestic violence a crime.

“In the cultures we came from, women did not stand up,” Hussein said. “The concept of someone physically assaulting you and going to jail for you is a new concept to us. Why would the government be in the middle of family issues?”

McGonagle, the Lewiston police lieutenant, noted that it wasn’t long ago that domestic violence was handled much differently in the U.S.

“Twenty-five years ago, we might go to someone’s house, tell the husband or boyfriend to go stay somewhere else for the night and that was it,” he said.

Now if there is a domestic violence call, the result is almost always an arrest.

Immigrants and refugees are counseled on domestic violence laws in Maine, but that doesn’t necessarily change anything.

Kubeloso was working the front desk at Hope House in Lewiston during a recent domestic abuse workshop that included information on how to safely leave a relationship.

Morrison, the Save Voices director, said forcing victims to talk about abuse can backfire.

“Because domestic violence is all about control, when victims come to us, the last thing we want to do is control them,” she said. “We try to empower them to make decisions.”

PRESSURES NOT TO REPORT ABUSE

The prospect of arrest also can be a deterrent to reporting domestic abuse.

Sue Roche, executive director of the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project in Portland, said the same dynamic plays out in cases involving immigrants or refugees.

“It’s all about power and control,” she said. “With immigration status, though, sometimes that becomes another method of control.”

Victims might be told, falsely, that if they go to police they will be deported. Abusers might use children as pawns.

In other cases, silence is about finances. If a husband or partner is jailed, they don’t earn a paycheck.

Morrison said she has seen cases where a woman sought a protection from abuse order against a partner, but withdrew it after pressure from elders or others in their community.

Joao said Kubeloso told her that she and Deus had been together too long for her to turn him in.

Perry, of Portland’s Family Crisis Services, said he’s heard of incidents where women have testified in court and translators, instead of relaying the judge’s or attorneys’ words, actually shame the victim.

“Of course, no one else in the courtroom usually knows what is being said,” Perry said.

Wentworth said Family Crisis Services takes care to use interpreters who are not based in Maine.

“We don’t want to risk them talking to someone who might be connected to their cultural community,” she said

Michaud has seen victims hide within their communities, choosing the familiarity and protection of their countrymen over possibly going it alone.

Hussein said most choose the former.

“Where we came from, we had people who resolved these issues,” she said. “The result was not jail or protection orders. The results were mediation through elders and maintaining families. In our culture, the more a woman keeps quiet, the more she maintains her family.”

Portland Deputy Police Chief Vernon Malloch said his officers have seen the same thing, and he believes some of it might be generational.

“Sometimes what we see as a default is to go back to tribal mechanisms to solve problems,” he said. “So rather than go to police or through the criminal justice system, they handle it internally. I think that will lessen with the next generation.”

General mistrust of police is common among newly arrived immigrants, who may have experienced violence at the hands of police in their home countries.

“When we say ‘Go to police,’ some have seen family members killed by police or sexually assaulted,” Perry said.

Domestic violence advocates see Kubeloso’s death as an opportunity to examine ways to reach immigrants or refugees.

Morrison, however, worries that her death might provide fodder for anti-immigrant groups.

“There are still plenty of people who are not happy that immigrants have come here,” Morrison said. “So they’ll use this as an opportunity to say, ‘That’s how they do.’ But that’s unfair. No race or culture or group is immune.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story