The Bowdoin College Museum of Art’s “Night Vision” is a major exhibition that explores a century of nighttime painting. Two great paintings from the museum’s collection, featuring radically different perspectives on the subject of night, bookend the show: Winslow Homer’s “The Fountain at Night, World’s Columbian Exposition” of 1893 and Andrew Wyeth’s 1944 “Night Hauling.”

The Homer, illuminated by electric light on Frederick MacMonnies’ great sculptural fountain, shows a fascination with world-changing technology. Wyeth’s work captures the remarkable but generally unremarked magic and mystery of the diurnal world illuminated by nature’s own phosphorescence and the workaday lantern of a laboring Down East lobsterman.

Bowdoin has gathered notable works from around the nation to create an unusually provocative and eye-opening show. The 90 works are anchored with expected major players, such as Ansel Adams, Albert Bierstadt, Charles Burchfield, Georgia O’Keeffe, Albert Ryder, John Sloan and Frederick Remington. But “Night Works” truly succeeds on its unexpected additions.

I was pleasantly surprised to see the Phillips Collection has loaned Ryder’s mid-1890s masterpiece “Macbeth and the Witches,” considering its wrinkled-like-a-prune condition. It, alone, is worth the trip to Brunswick. It is a challenging painting, since the narrative is almost impossible to parse. But oh, how that mystery is delicious: The Weird Sisters, who prophesy Macbeth’s ascent (and later his downfall) are the embodiment of chaos, conflict and the darkness of the human soul. Ryder’s binding them to the immateriality of night darkness (and the seed of doubt as a dream thought) makes for one of the greatest representations of the terrifying trio. Ryder’s moon grabs the corner of a cloud, lighting its rim with the effect of a Marsden Hartley-style cloud wandering in to dominate an otherwise 19th-century symbolist landscape.

Another excellent surprise is a suite of two paintings and two drawings by Edward Steichen, particularly his stunning 1905 symbolist canvas “Shrouded Figure in Moonlight,” in which an unfathomable figure appears under a dark and distant wooded landscape witnessed by a peering moon. Coupled with his photos, Steichen’s work on the edge of darkness finds a deeply unsettling power.

Henry Ossawa Tanner may be the biggest discovery for many visitors. His night-lit disciple at Jesus’s tomb is impressive and moving, and his “Salome” is an exquisite combination of brazenly sexual allure and unbridled terror.

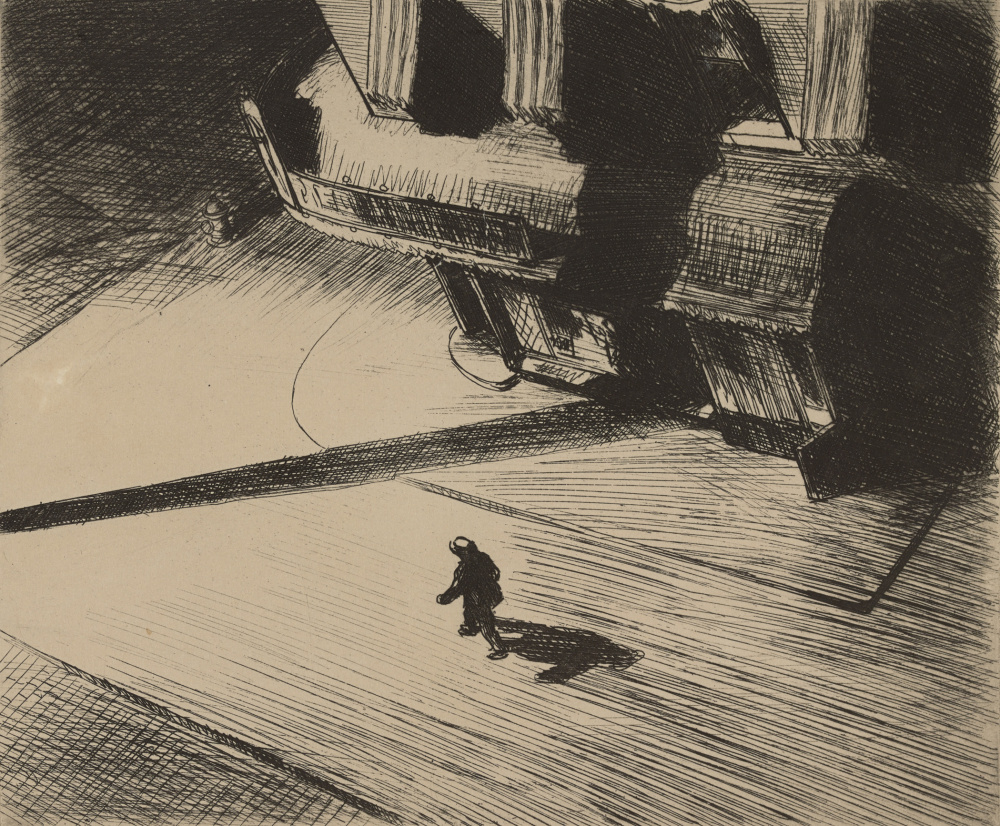

While the prints in “Night Vision” are introduced by Homer’s insightful eye, they only achieve genuine power with the 1920s city night scenes of Edward Hopper and Martin Lewis. Lewis in particular is a powerhouse of perception, psychology and the nighttime urban landscape. His images of a flapper descending the wooden Fifth Avenue Bridge and of a silhouetted woman in nightclothes peering longingly from under her laundry toward the lights of a Manhattan skyscraper bookend the desires and vulnerabilities of a sexualized female in the modern American city. They are extraordinary works of art.

Night comes into focus as the modern century’s new frontier. We believe we have conquered it with electric lights, but night has fought back with dream logic, fear and the id world of sex and violence – not unlike how the witches show Macbeth his ascension but return to deliver conflict and his downfall.

On a basic level, with the newly lit American city, we leave behind day and its obligated labor for the freedom of night – the place of dreams, desires, sex and entertainment, where people go to feed their true selves. This happens innocently at first with Homer’s journalistic images and John Sloan’s Ashcan School scenes. But, as the culture moves into the modernist century (and internalizes the processes and appetites of Freudian psychology), possibility devolves into darkness.

“Night Vision” takes on a fascinating and deeply ambitious subject that is so vast as to be beyond attainable encyclopedic completeness. This sets our expectations toward works that touch on a theme, rather than a comprehensive exhibition. In this sense, “Night Vision” is extremely successful.

It is not without flaws, however. As an exhibition that links American art to its broader culture, it misses the opportunity to connect the introduction of Freudian thought to American culture and art. It was here in America where, after the 1899 publication of “The Interpretation of Dreams” and Sigmund Freud’s 1909 visit to this country, his ideas about subconscious and dream logic broadly crossed into artistic culture, mainstream culture and the public understanding of the human mind.

The psychoanalytic orientation of Surrealism, which specifically linked itself to Freudian processes like free association, was the vessel American art rode to the fore of the international art world. “Night Vision” largely misses American surrealism. George Tooker’s impressively odd “Dance” of 1946, for example, remains a high-focus oddity looking back to the moralizing Middle Ages in which Death, in the guise of a skeleton, appears on a New York Street to claim a victim. And Lee Krasner’s large (and gorgeous) sepia-toned painting from her “Insomnia” series is left, rather ineffectively, to brush against themes requiring backreading and biography.

In the end, Wyeth’s “Night Hauling” remains the outlier it always was in his oeuvre. But, wandering unconnected, it joins many other outliers, like Werner Drewes’ severe, Kandinsky-connected “Night Fantasy” or Arthur Bowen Davies’ gorgeously delirious landscape of slumbering maidens echoing the symbolist style of Puvis de Chavannes, “Sleep Lies Perfect in Them.”

While we most commonly use the term “nocturne” to talk about a quiet, single-movement mode of 19th-century music for solo piano, Bowdoin curator Joachim Homann, with appropriate apologies, employs it to open the door to a vast world of night. I see it as reclaiming America’s true roots in Romanticism, as opposed to Enlightenment logic: The frontier, fear, the sublime and the dream drove the first Europeans to America, and we have never lost that sense of direction. “Night Vision” makes the tacit and compelling argument that it was Whistler who truly lit this cultural candle in 1875, when he launched his ceaselessly controversial masterpiece “Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket,” a missile that has never stopped exploding.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story