FORT MYERS, Fla. — If the idea of taking a baseball player who has appeared in 1,194 big league games in the infield and erasing a 92-game interlude in the outfield and making him an infielder again would seem, in a word, easy, Hanley Ramirez is here to stop you before the second syllable escapes your lips.

“Nothing easy,” he said here Monday. “Nothing easy. Nothing easy.”

A couple hours later, as if to prove his point, Ramirez planted his foot on the first base bag and turned over his massive claw of a first baseman’s mitt. A one-hop throw came to his feet, and it bounced away. The error went to third baseman Pablo Sandoval. An experienced major league first baseman scoops that ball more often than not.

“I don’t think he is where we want him to be right now,” said Brian Butterfield, who has coached infielders for decades. “But we expect him to keep getting better, and he is getting better.”

There is so much to like at Boston Red Sox Florida headquarters, where three last-place finishes in a four-year period must be flushed away. One step in that direction was signing ace lefty David Price, who they deemed worth $217 million over seven years. Another is employing a dynamic young nucleus, with shortstop Xander Bogaerts, catcher Blake Swihart and right fielder Mookie Betts all 23, slightly younger than 25-year-old center fielder Jackie Bradley Jr. Still another is by making the most of David Ortiz’s final season as a Hall of Fame-caliber designated hitter, and another is by hiring a proven executive, Dave Dombrowski, to oversee it all.

But for the Red Sox to be the best version of themselves, to win what would appear to be a wide-open American League East, Sandoval and Ramirez, signed for a combined $183 million last offseason, must make their defense a non-issue.

The season is a less than a month away. It is, at the moment, an issue.

“It’s a situation where there’s certainly some work to be done,”Red Sox Manager John Farrell said prior to Monday’s Grapefruit League game against Tampa Bay.

Farrell was talking, in that moment, about Sandoval’s defense, which was the worst among all third basemen last year as measured by the advanced metric “defensive runs saved.” By that measure, Sandoval cost the Red Sox 11 runs. By contrast, the leader among third basemen, Texas’s Adrian Beltre, saved the Rangers 18.

Those stats, this spring, don’t matter. This moment, from Monday, won’t matter in a month. But it says something about where this process currently sits. Rays third baseman Evan Longoria led off the top of the fourth with a chopper to Sandoval at third. Moving to his left, he gloved the ball but struggled to turn his body and fire the throw to Ramirez. This came some six hours after Ramirez began his initial first base drills of the day, some four hours after he took hard grounders off a coach’s fungo bat meant to simulate the skipping action of a throw in the dirt.

“I’m not worried about him,” veteran second baseman Dustin Pedroia said. “He’ll be great.”

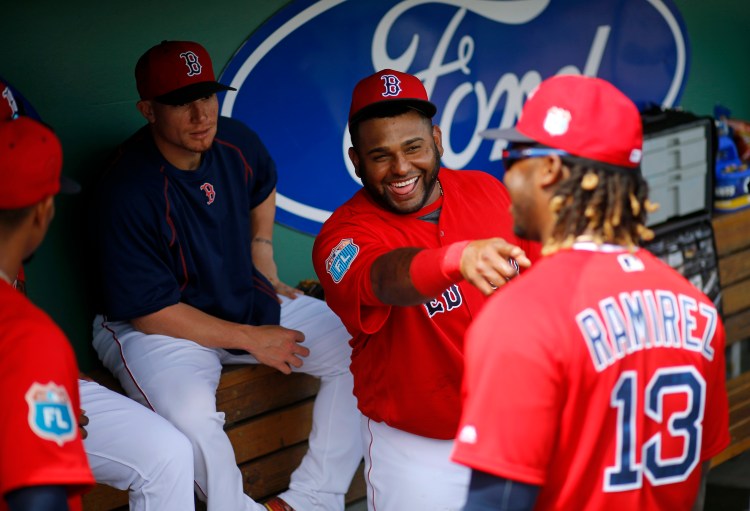

“He looks good over there,” Sandoval said. “He’s working hard. He’s such a great athlete out there.”

Here, though, Longoria was safe for two reasons: Sandoval couldn’t get enough steam on the throw so that it didn’t hop, and once it did hop Ramirez couldn’t dig it out.

Consider Ramirez’s side of things first, then. A decade ago, when he was a 22-year-old shortstop with the (then-Florida) Marlins, he beat out Ryan Zimmerman for the 2006 National League rookie of the year award and was on the short list of players around which you would choose to build a team. He became a three-time all-star at the position, then was traded to the Dodgers, who used him at third base some as well.

But until he signed his four-year, $88-million deal with Boston before the 2015 season, he had never played a game in the outfield. The Red Sox put him in left. There, he crashed into a wall, injuring his left shoulder. The entire season – a .249 average and .717 on-base-plus-slugging percentage in 105 games – was lost. “I learn from my mistakes,” Ramirez said. This offseason, a new plan: first base.

“I think the fact that he’s back on the infield, he’s in every play much more,” Farrell said. “He’s part of a unit on the infield as opposed to maybe a singular position in the outfield.”

There was, when Ramirez played left, a question about his focus. Shortstops are in the middle of so much, locked in on every situation, every pitch. Left fielders … well, the mind can wander.

“Just from watching some players try go from the infield to the outfield, because you are further away and you’re not getting the ball, you’re not getting as many chances, you might not be as engaged,” Butterfield said. “But he understands now that he’s going to handle the ball more than anyone on the field other than the catcher. And I think he’s looking forward to that responsibility and taking care of his other infielders.”

This is, though, a process. By all accounts, Ramirez is doing his part, showing up at 8 a.m. to drill with Butterfield before regular workouts start. They go over footwork. They address the first baseman’s responsibilities on relay throws. They discuss how to play balls when theRed Sox employ a shift, which is more than occasionally.

“I mean, this game is about confidence,” Ramirez said. “We go out there and do little things, try to cover everything, try to build some confidence by the time the games start.”

Sandoval professes no such confidence issues. Three batters after Longoria’s grounder, Steve Pearce scalded a ball that ran up Sandoval’s left arm, squirting away. “Nothing I can say,” Sandoval said afterward, laughing.

“It’s just to make the things simple,” he said. “Try to make the play.”

There is an element of Sandoval that gained attention the day he arrived here, and it draws the eye still: His girth. It is, well, substantial. And it garners attention because a professional third baseman worthy of a five-year, $95-million deal, a bona fide World Series hero, should be able to regularly make the plays required of his position.

“I thought he got to the ball to his glove side in good fashion,” Farrell said afterward, “but to redirect himself and make a strong enough throw to carry the distance across the infield,” and he trailed off. Left unsaid: He couldn’t do it. Sandoval and Butterfield are working, then, on first-step quickness, which would in turn better set him up for the throw.

“The range is gonna be the range,” Butterfield said. “It is what it is. But the biggest thing is: We want him to catch the balls that are within his range.”

In April, no one will remember that the two errors – not to mention a substandard feed from veteran second baseman Dustin Pedroia to Bogaerts on a potential double-play ball – led to two Rays’ runs in what became a 3-2, 10-inning loss. It’s early, until it’s late.

“There might be some mistakes made,” Butterfield said. “We’re taking a snapshot now – and we’re going to take one in three weeks.”

The snapshot, on Monday, was fuzzy. Opening Day is still four weeks away. By then, maybe it will seem easy.

“You got to put work in, and every day go out there and do your job, and try to get comfortable,” Ramirez said. “Nothing is easy in life. In this game, nothing is easy, either.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.