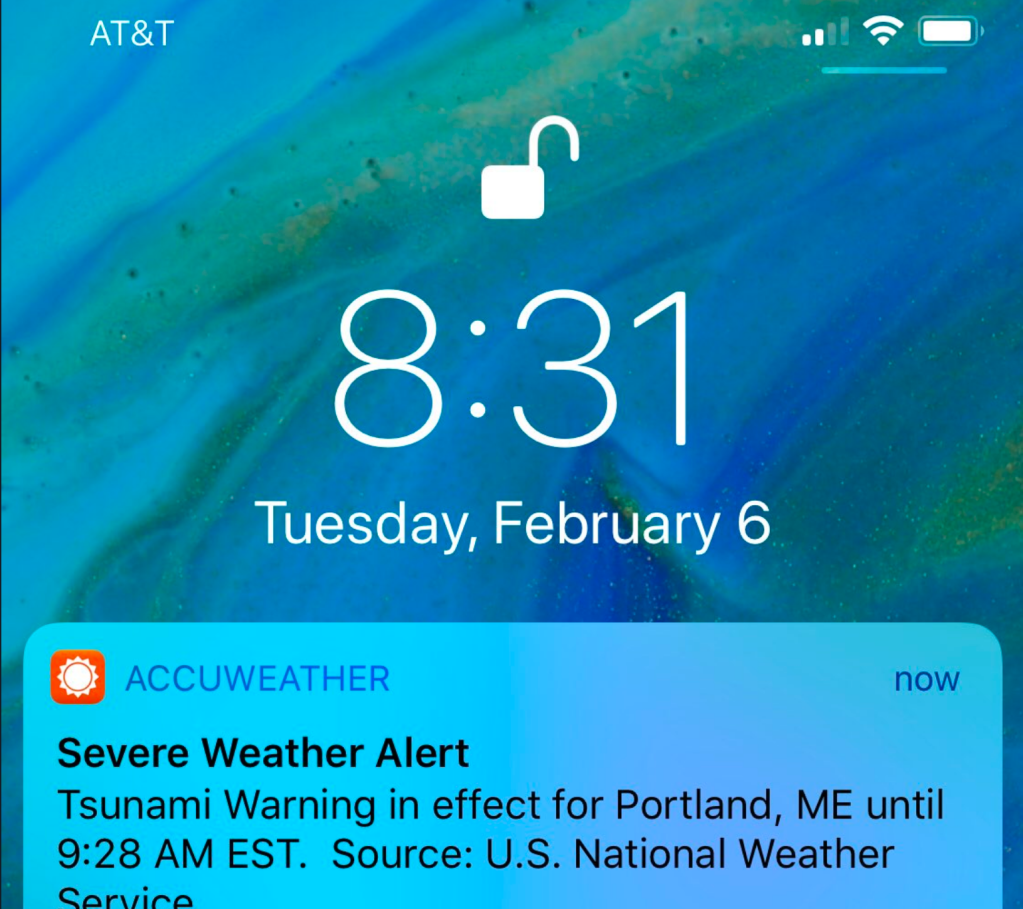

Smartphone owners from Maine to Texas who have the AccuWeather app likely did a double take when they received a tsunami warning Tuesday morning. It turned out to be a National Weather Service test that had gone awry, but that wasn’t immediately apparent on cellphone screens.

Jeremy DaRos of Portland said the alert made him “jump” because he lives close to the water and was aware of a recent spate of small earthquakes in Maine that made the alert seem plausible. He realized the alert was a test after clicking on the push notification for details.

“Looking out the window and seeing the ocean puts you in a different frame of mind when you get a tsunami warning,” he told The Associated Press.

The false alert went out along the entire East Coast and Gulf Coast from Maine to Texas, as well as in the Caribbean.

AccuWeather released a statement more than four hours after the alert blaming the mistake on a miscoded test issued by the weather service, and said it wasn’t the first time the federal agency made such a mistake.

However, officials from the weather service seemed to point blame at AccuWeather, saying “at least one private sector company” released the agency’s test message as an actual warning.

“The National Tsunami Warning Center at the National Weather Service issued a test message at approximately 8:30 a.m. ET this morning. The test message was released by at least one private sector company as an official Tsunami Warning, resulting in widespread reports of tsunami warnings received via phones and other media across the East Coast, Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean,” the weather service said in a statement.

Officials at the weather service office in Gray office said they were not authorized to speak about the alert and could not even answer questions about the history of tsunamis in Maine.

In its statement, AccuWeather said it has “the most sophisticated system for passing on NWS tsunami warnings based on a complete computer scan of the codes used by the NWS. While the words ‘TEST’ were in the header, the actual codes read by computers used coding for a real warning, indicating it was a real warning.”

“Tsunami warnings are handled with the utmost concern by AccuWeather and it has sophisticated algorithms to scan the entire message, not just header words, as from the time of a warning to the actual event can be mere minutes,” the statement said. “AccuWeather was correct in reading the mistaken NWS codes embedded in the warning. The responsibility is on the NWS to properly and consistently code the messages, for only they know if the message is correct or not.”

The weather service pushed back on AccuWeather’s assertion Tuesday night.

Weather service spokeswoman Susan Buchanan told the AP that the agency’s investigation found the routine monthly test message was properly coded. She says the weather service is “working with private sector companies to determine why some systems did not recognize the coding.”

The National Tsunami Warning Center said it did not issue a tsunami warning, watch or advisory for any part of the United States or Canada Tuesday morning. The center, based in Palmer, Alaska, issues monthly tests to regional weather offices.

Officials said it appeared to be an issue only with the Accuweather app.

Susan Faloon, public information officer for the Maine Emergency Management Agency, said her agency received an email from the National Weather Service about a test of the tsunami alert system, then a follow-up email reiterating that there was not an actual tsunami alert in effect.

If there had been an actual tsunami warning, MEMA would have sent out a message through its emergency alert system. That warning cannot be done with the push of one button to avoid alerts from going out inadvertently, Faloon said. The agency did not receive phone calls from people inquiring about the accuracy of the alert sent out Tuesday.

Last month, a Hawaii state employee mistakenly sent at alert warning of a ballistic missile attack. That Jan. 13 alert caused panic on the islands when it took 38 minutes for emergency officials to retract the warning. A week later, a malfunction triggered sirens at a North Carolina nuclear power plant.

Faloon, from MEMA, said despite the spate of recent false alerts, people should still take emergency alerts seriously.

“The unfortunate thing with all these recent incidents is we don’t want people to ignore them in the future,” she said. “Those are still very important messages people should pay close attention to and seek out additional information about from a local news source.”

904AM: A Tsunami Warning was mistakenly sent by an app. There is no Tsunami Warning in effect. It was just a Tsunami test message.

— NWS Miami (@NWSMiami) February 6, 2018

We've seen reports that some people have received an erroneous tsunami alert. There is NO tsunami threat to Maine. #mewx #nhwx

— NWS Gray (@NWSGray) February 6, 2018

Most tsunamis occur in the Pacific Ocean because of seismic and volcanic activity there, and only small tsunami events have been recorded in Maine. According to National Weather Service records, small waves of less than 50 cm were recorded by gauges in Penobscot Bay in 1872, but the sources of the waves is unknown. In 1926, a wave suddenly reached 10 feet and flooded Bass Harbor.

A 20-foot-high tsunami spawned by an earthquake on Grand Banks hit Nova Scotia and possibly spilled into the Gulf of Maine in 1929, wiping out fishing villages and killing 28 people. There are no records in Maine of damage from that tsunami, according to the Maine Geological Survey.

While a tsunami in Maine is unlikely, state and local emergency management officials have prepared for the possibility that one could impact Maine if there was major geological activity like an earthquake or volcanic eruption in the Atlantic Ocean. Cumberland County commissioners in 2012 accepted a $39,000 grant to help pay for educational materials associated with a tsunami threat.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story