Richard Blanco writes in the introduction to his new book of poetry that he has been crossing boundaries since before he was born. His mother was seven months pregnant with him when they left Cuba for Spain. Days after Blanco was born in 1968, the family moved from Spain to New York.

When he was 4, he moved again, from New York to Florida – to Miami, where he spent his young life straddling a “cultural boundary between the two halves of my hyphenated identity as a Cuban-American.” On one side of the hyphen was “a mythic, nostalgic view of Cuba that loomed large in my psyche through family lore about a homeland I belonged to but had never seen.” On the other side of the hyphen was Blanco’s storybook America that he constructed from textbooks and TV.

Later, as an adult, he negotiated boundaries between being straight and gay and living as a Latino in a small town in Maine. “It’s no wonder that boundaries became an obsession and a dominant theme that I’ve explored, and continue to explore, through my poetry and my life,” he writes.

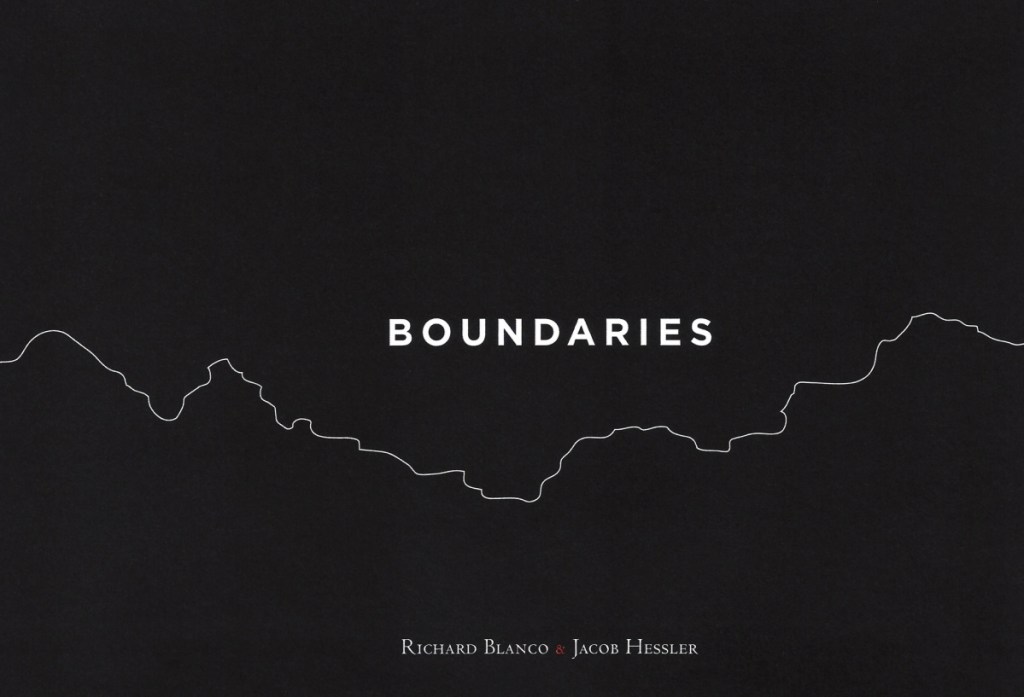

The book is called “Boundaries.” In collaboration with midcoast photographer Jacob Hessler, Blanco explores the idea of boundaries, real and imagined, in contemporary America. An exhibition of the same name, with Hessler’s photos and Blanco’s text, is open at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland through May 27. There’s a reception from 1 to 4 p.m. Sunday, and Blanco will read at 1:30 p.m.

It’s a quiet, reflective exhibition that asks viewers to consider the boundaries that divide us by race, gender, class and other ways. As artists, the two attempt to tear down barriers to create understanding, empathy and compassion. “This exhibition speaks so well to current issues in culture and politics,” said Suzette McAvoy, the art center’s executive director. “The artists address the issues not bluntly, but poetically.”

Hessler is a landscape photographer from Camden. Blanco is a poet from Bethel, best known for writing and delivering the poem “One Today” at President Barack Obama’s second inauguration in 2013. He was the first immigrant, the first Latino, the first openly gay and the youngest person to deliver an inaugural poem.

McAvoy timed the exhibition to coincide with the Camden Conference, a current-affairs gathering dedicated to global issues. This year, the conference explores the shift in global power, the impact of globalization and the rise of nationalism. McAvoy wanted an exhibition to tie in thematically with the three-day conference. Centered two towns up the coast in Camden, the conference, which concludes Sunday, includes events at the Strand Theatre in Rockland.

This is the second time “Boundaries” has been shown. The Coral Gables Museum in Florida showed it in the fall.

In separate interviews, each artist said he was motivated by the idea of erasing boundaries that divide people for the sake of power and oppression. The exhibition is presented to look like the book on the wall, in large scale. The photos are 40 by 60 inches, printed on aluminum that floats off the wall.

The poems are enlarged versions of the page spreads from the book, wall-mounted behind glass. A center case displays a deluxe version of the limited-edition book with an original Hessler photo and a page of poetry with Blanco’s notes.

Hessler designed an elegant book, which was published by Rockport-based Two Ponds Press. The book has 12 photos and poems. The CMCA show has nine. The exhibition in Florida included six.

Blanco visited CMCA for a fundraiser last summer and fell in love with the contemporary feel of the space. With photos and text, this show feels appropriate for the flexible nature of the light-filled exhibition space, he said. It’s open and flowing, and it enhances the atmospheric feeling of Hessler’s photos.

“It’s a great home for us there,” he said. “It lends itself to the spirit of the book.”

Blanco and Hessler met at party after the Obama inauguration, hosted by Rep. Chellie Pingree. Later, Hessler and his wife, Alissa, helped Blanco with his website and online presence. As they got to know each other better, they began exploring collaborations.

“I really fell in love with his work,” Blanco said. “I was attracted to the sense of the scale, the format and the fact that the photographs are, for the most part, devoid of any human. That’s interesting to me as a writer. It invites a narrative to be written about it. You can walk into the photographs and create a story.”

Hessler is represented by Dowling Walsh Gallery in Rockland and has shown his photos at CMCA previously. “His approach to the landscape is poetic, and it mirrors the poetry of Richard Blanco,” McAvoy said.

Hessler began gathering photos for “Boundaries” while driving around the country, which is common practice for him. He’s driven across the United States 10 times, always for a project. “My wife and I were traveling, shooting for different projects and shooting for this one at the same time. We drove across the country, down the entire East Coast to Corpus Christi, over to California and up to Oregon and then back across again,” Hessler said.

He took the photos for “Boundaries” before the election of 2016, when Donald Trump won the presidency. After the election, Hessler and Blanco both felt an urgent desire to finish the project. Nationalism was on the rise, and there was talk of closing borders. “We wanted to get it out there,” Hessler said. “We needed to get it out there.”

Hessler’s photos feel translucent and distant, almost dream like – or nightmarish. In San Diego, with a robin’s-egg blue sky high in the background, he shows the rusted see-through border wall at Tijuana and frames a group of people on the other side by the open spaces in the wall, the details of their forms obscured by sand or haze.

There is a photo from Maine in the book, though it’s not in the CMCA exhibition. “Main Street, USA, 2016” portrays downtown Belfast on a foggy November morning, the dawn after the election. The Colonial Theatre and its brightly colored facade and life-size rooftop elephant brighten the gloom.

Blanco writes in “November Eyes on Main Street”:

“I question everything, even the sun today

as I drive east down Main Street – radio off –

to Amy’s diner. She bobby-pins her hair, smiles

her usual good mornin’ but her eyes askew say

something like: You believe this? as she wipes

the counter, tosses aside the Journal Times,

the election headlines as bitter as my coffee

that she pours without a blink.”

Blanco’s writing process for this book was different from anything he’s done before. He researched Hessler’s photos for historical content and background, so he could write with specificity, credibility and precision, “and to do the photos justice. It challenged me in a way I am glad for. I would spend hours just doing research.”

An example of this approach is the poem “Easy Lynching on Herndon Street,” which, again, is in the book but not in the show. Blanco uses the framework of Hessler’s photo of a verdant, canopied residential street in Mobile, Alabama, to tell the larger story of the last known lynching in the United States, in 1981.

“What I’d rather not see isn’t here: no rope,

no black body under a white moon swaying

limp from a tree, no bloodied drops of dew

on the twenty-first of March 1981. That’s

in another photo, like a dozen other photos

I’ve gaped at wanting – not wanting – to turn

away from the snapped necks of the hanged,

and the mob’s smug smirks, asking myself

How could they? Why?”

He turned Hessler’s photo of a stand of aspens in eastern Arizona into a story about the long walk of the Navajo. It’s less a poem about what we see in the photo and more an investment into what the photo doesn’t show.

Blanco wrote all of these poems at his home in Maine, his safe haven, the end of the line and the last stop before the border.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.