Keri Bush kept her mom’s recipes in an old wooden box filled with 3-by-5-inch recipe cards in her Paradise, California, home. It had instructions for all of her Christmas treats along with her mother-in-law’s pie crust, passed down from her father, who was a baker.

Bush never got a chance to get to her home on Nov. 8 before the flames consumed it. She was already at work in nearby Chico when the fire spread rapidly through her town. Her husband had just enough time to get back to the house to wake their 18-year-old daughter and grab the pets and a few important documents. Everything else was lost.

“The phrase ‘it’s just stuff’ is so frustrating,” Bush said. “The fact is that I’ll never be able to get these things back.”

The Camp Fire decimated the town of Paradise, and months later many are still struggling to find jobs and a place to live in the surrounding area. Fire survivors like Bush, who want to start cooking again, face the challenges of temporary housing, lack of equipment and the loss of their family recipes. But a group of dedicated helpers is trying to salvage lost recipes by replacing old cookbooks and re-creating instructions for these well-loved dishes, which have been passed down through many generations.

It didn’t take long for her to miss the recipes. Three weeks after the fire, Bush responded to a thread in the Facebook group Paradise Fire Adopt a Family that asked, “Is there a small comfort item we can find that will feed your heart and soul?” Bush asked for handwritten recipe cards.

Debra Brown saw Bush’s request and started gathering recipes from friends around the world. Brown, who grew up in California and now lives in Plano, Texas, put together a cookbook divided into seven sections, including appetizers, meat and poultry, soups and salads, and desserts. It took her 52 hours of work to handwrite the cards and arrange them into a scrapbook.

Keri Bush’s mother-in-law’s pie, the recipe for which is now lost. Photo by Keri Bush

“Sometimes an idea just overcomes you,” said Bush. “I thought, ‘I can really do this. I can make her feel that my friends are her friends.’ ”

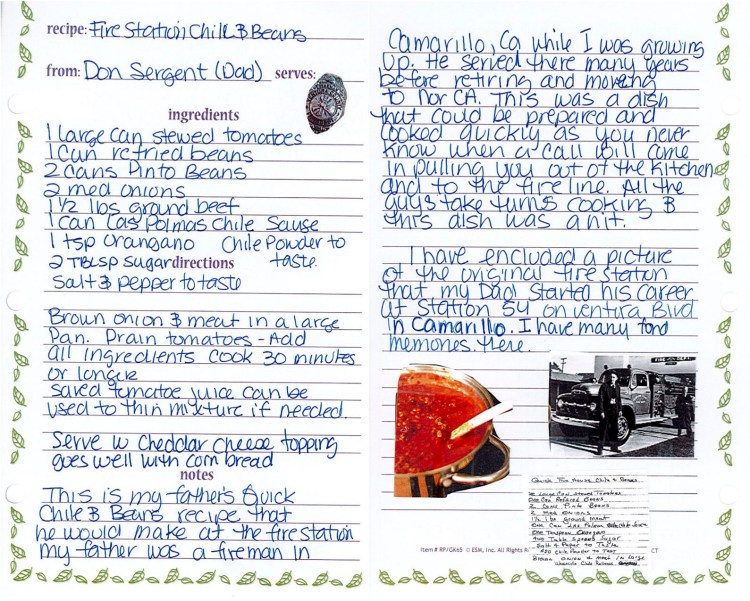

The book isn’t just a compilation of recipes – it’s filled with photos, doodles, stickers and back stories about the recipes as well as the person who shared them. Brown’s father was a firefighter in Camarillo, California, in the 1960s and 1970s. She included his Firehouse Bean Chili along with photos of his old station house and his badge.

Brown’s friend Andrew, who lives in Australia, contributed a recipe for traditional calico Christmas Pudding, which is usually cooked in a cloth. According to Andrew, one day his grandmother discovered her mother-in-law cooking the treat in one of her old bras. “From that year on, the pudding was made by my grandmother instead.”

Brown scanned the book for her files and sent it to Bush, who was overcome when she began to thumb through it.

“It was a bright moment in a very dark place,” said Bush. “I was actually crying tears of happiness instead of sadness.”

The book can’t replace what Bush has lost – she still longs for her family recipes – but it’s become a memento, and a starting place to talk about healing from the fire.

“I’ll be able to pass it along to my kids along with a great story,” said Bush.

Brown has sent the book via Dropbox to other Camp Fire survivors who have reached out, although the digital version doesn’t have the same analog feeling of the three-ring binder with colorful pasted-on images of food and people.

The internet has made it easier to recover popular recipes, but many fire survivors are longing for a connection to the past. And for cooks, those connections are often tactile. Those who have lost their recipes don’t just miss the instructions – they miss seeing their mom’s loopy handwriting, or the footnotes to add more butter to a crust – all the tiny generational tweaks that turn a family recipe into a living document.

Melissa Gianotti, a librarian who lives in Pleasanton, a city 175 miles south of Paradise, is helping replenish lost books with a network of volunteers and helpers, but says most people ask for used cookbooks, not new ones.

She gets the most requests for the original Better Homes and Gardens cookbook and early editions of the “Betty Crocker Cookbook” – each fetching a hefty price tag on eBay. Often the fire survivors are looking to replace volumes handed down to them by a parent or grandparent, or gifts they received for their wedding.

“They want the old ones with the notes in pencil and the smears of chocolate on them,” Gianotti said. Occasionally, these well-loved tomes show up in bags of donations, and she’s been able to get a few out to those who have asked.

The fire has changed daily cooking for many survivors, especially families who are living in RVs, FEMA trailers and temporary housing. Gianotti often gets requests for Instant Pot recipes, because cooks without counter space or an oven can use these pressure cookers to make homemade meals for their families, a healthier and cheaper option than eating out. But many of these cooks never used an Instant Pot before the fire and are finding the steep learning curve of using multicookers challenging.

Other cooks, such as Avalon Kelley Glucksman – who lost her home in the fire and dreams of opening her own restaurant one day – struggle to recreate Old World dishes after being out of the kitchen for months.

The hundreds of pages of handwritten Hungarian recipes that were passed down from Glucksman’s grandmother are gone. Some of the dishes – such as the goulash or beef stroganoff – she knows by heart. But others, such as the sour cream pie and the cumin and egg omelet, remain a mystery. Glucksman was living without a kitchen for months after the disaster and has lost some of the muscle memory in recreating the dishes. She has had little luck replacing her Hungarian and Eastern European cookbooks.

“I can only try to recreate the taste of my ancestors,” she said.

A devoted community of volunteers is trying to reconstruct recipes and make daily cooking for survivors a little easier. The Facebook group Camp Fire Cookbook of Love is a place for recipe exchanges, where people share their family favorites for a wide variety of dishes, including chicken cacciatore and aebleskivers. In a modern-day take on the old church fundraiser, volunteers are collecting Google Docs of recipes from across the country and compiling them into a book, with a goal of raising $10,000.

Tanessa Smith with her husband, Jacob Smith; daughter, Jordan Smith; and son, Christopher Smith, in front of what was their Paradise, Calif., house. Photo by Tanessa Smith

Another survivor, Tanessa Smith, has turned to the group for ideas on replacing some of her lost dishes with new versions. Smith, who relocated to Idaho after the fire, lost the recipe book her mom had handwritten and given to her 14 years ago, along with hundreds of cookbooks, for Christmas.

“You could call me a foodie,” said Smith. “I had a huge cookbook collection, but I went to my mom’s recipes first.”

Smith said she’s grateful for the volunteer efforts but misses her mom’s recipes because they were tried and true. The star was her mom’s cobbler, which Smith took to potlucks and parties for more than a decade.

Smith’s mother is still alive, but her health is declining, and she can’t recreate the collection.

“I had footnotes in there – “too much flour, or too much salt. My daughters had drawn rainbows on the back of some of the recipes,” said Smith.

“They were her recipes, but I had made them my own.”

Amy Ettinger is the author of “Sweet Spot: An Ice Cream Binge Across America” (Dutton, 2017).

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story