AUGUSTA — A proposal by the Greater Augusta Utility District and city of Augusta to partner with a private solar power provider to build a solar farm on unused district property in Winthrop could lower their electricity costs and make Augusta the state’s first municipality to cover all of its electricity costs through renewable sources.

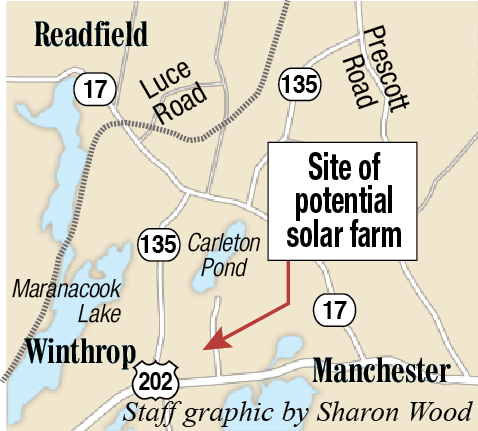

Greater Augusta Utility District officials are considering a proposal to contract with a solar development firm to build and run a roughly 3.9 megawatt solar farm on land next to the utility district’s unused water treatment plant below Carleton Pond in Winthrop.

The solar array would produce electricity that would be delivered to the Central Maine Power Co. grid, with both GAUD and the city of Augusta getting credits on their electric bills for the power they feed into the grid. The two entities would then use those credits to offset their electrical bills from CMP.

In the city of Augusta’s case, the project would mean 100 percent of the electricity consumed at city buildings. And if school officials agree, the cost of electricity to school buildings would also by offset by power coming from renewable sources.

The city already has a system at the Hatch Hill landfill that uses methane gas captured from rotting material in the landfill to produce electricity for city and school buildings. This provides a credit on the city’s electric bills equal to the electricity used in nine city and school buildings.

Ralph St. Pierre, finance director and assistant city manager in Augusta, said if the joint solar project with GAUD goes online, it would provide about 1.4 megawatts of power to the city, which he said would be enough to provide electricity to all city and school buildings not already using electricity provided through the Hatch Hill system. That, in turn, would make Augusta’s sources of electricity all renewable sources.

While having all of the city’s electricity come from renewable sources would have a variety of benefits, St. Pierre said the key attribute of the proposal is it would lower the electrical costs for both the city and utility district.

He said the GAUD project could save the city about $70,000 a year in reduced electrical costs, on top of the approximately $60,000 a year the Hatch Hill system saves in electrical costs, for a total annual savings to the city of $130,000 from the “green” initiatives.

“We like being renewable, but like the other green (from saving money) better,” St. Pierre said. “It had to be cost-effective.”

The developer of the solar farm would make revenue by selling the electricity the solar farm produces to GAUD, under a proposed 20-year contract the utility’s district board of trustees is scheduled to consider Monday, at less than its cost of producing that electricity. The developer could also take advantage of federal tax credits.

The city and GAUD would pay about 7 cents per kilowatt for the electricity produced by the private company, while getting a credit from CMP of about 13 cents per kilowatt, thus resulting in savings of about 6 cents per kilowatt.

Charlie Agnew, director of energy services for Portland-based Competitive Energy Services, a consultant working on the project for GAUD, said he expects the district will get roughly $75,000 in savings from the utility bill credits from the solar project. He said the solar farm will provide about 50% of the district’s total annual electricity usage.

Maine Municipal Association officials knew of no Maine municipality currently relying 100 percent on renewable sources for its electricity.

The city of Belfast offsets almost 90% of its electricity costs from solar power arrays.

A 970 kilowatt solar array at Kennebec Sanitary Treatment District in Waterville is expected to save the district about $2,000 a year and provide credits to offset about 84% of its electricity.

St. Pierre said the GAUD project is feasible due to legislation passed in the last state Legislature: LD 1711, a net energy billing credit rule change that allows municipalities to apply such credits to up to 200 electrical accounts, up from the previous limit of nine accounts. He said that was significant because most municipalities have many different accounts, including separate accounts for streetlights.

Still to be determined before the project moves forward is who will cover the cost of connecting to the CMP grid.

Brian Tarbuck, superintendent of GAUD, said that could cost around $300,000.

Agnew said that cost could be covered by GAUD, or absorbed by the developer.

St. Pierre said if GAUD covers the cost of connecting, the city could help pay back that expense in a long term cost-sharing agreement.

GAUD and the city are also seeking a third partner to join in the project, a partner that can commit to the proposed 20-year agreement. If they cannot find a partner, the size of the project would likely be reduced to about 3 megawatts, which could reduce the amount of potential savings involved.

Tarbuck said they started looking into solar power after seeing a presentation at a trade show, and he was also aware the Kennebec Sanitary Treatment District gets most of its electricity from solar panels.

He echoed St. Pierre’s thoughts that while there are environmental benefits to the project, the financial incentive of saving ratepayer and taxpayer money is prime.

“The idea holds promise that we and the city will save our customers/constituents money by reducing the cost of electricity,” Tarbuck said in an email. “The other benefits of getting power that doesn’t require burning something and helps strengthen the regional grid through the use of distributed generation sources are certainly noteworthy.

“It’s important for our customers to know that while there are environmental benefits our motive is the long-term stabilization of rates and cost reduction first.”

Officials considered other sites, including next to Hatch Hill, but the electrical system did not have enough capacity there to take on the additional load. St. Pierre said the grid in the area of the treatment plant in Winthrop has enough capacity to take on the up to 3.9 megawatts the proposed solar system could feed into it.

While the solar farm has yet to be designed, Agnew said, the setup, based on a per-installed-watt estimate of $1.75 per watt, could cost about $7 million and cover about 10 acres at the unused GAUD site. The developer would likely get a no-cost lease for the land on which the solar panels would be located.

The Carleton Pond treatment plant, built at a cost of $12 million, closed and was relegated to backup status in 2004, when district officials decided to draw water from three wells that were drilled in 1955 and 1965. Because of a cheaper treatment process for well water, water could be taken from the wells for about $500,000 less a year than from Carleton Pond.

Tarbuck said the district maintains the treatment plant site so the district has water supply options, in case it needs increased water in the future.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story