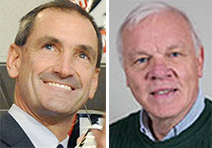

Rand Stowell and Chris O’Neil had a decision to make.

It was January 2014, and the two men – the driving forces behind the nonprofit wind opposition group Friends of Maine’s Mountains – had been fighting a Massachusetts firm for four years over the development of a wind farm in the western Maine mountains.

They could continue to challenge Patriot Renewables, even though almost all options had been exhausted and they couldn’t find an attorney willing to take the case.

Or they could drop their appeal of the Saddleback Ridge development and refocus efforts on challenging one of Maine’s many other wind projects.

Stowell and O’Neil chose a third option: They agreed to abandon the legal battle with Patriot Renewables in exchange for a financial settlement. The amount was not disclosed, but former board members who were involved said the payout was at least $200,000.

In other words, the state’s most well-known wind opposition group took money from the very industry it had been fighting. And in order to reach the settlement, Stowell and O’Neil used their power – and the limitations of Maine laws regarding nonprofits – to remove three board members who didn’t support a settlement.

A big chunk of the settlement money went to O’Neil, who was not only a board member but was working for Friends of Maine’s Mountains as a paid lobbyist and public relations consultant. Part of the settlement paid his outstanding fees.

For Stowell, the settlement with his organization triggered another settlement in a separate lawsuit he filed personally against Patriot Renewables as an abutting landowner. Stowell has not said how much he was paid.

Their decision led to an investigation by the Attorney General’s Office, which concluded that “Stowell and O’Neil participated in improper conflict of interest transactions and engaged in improper governance practices.”

As part of an agreement, the AG’s office requested wholesale changes to the Friends of Maine’s Mountains operation, but neither Stowell nor O’Neil had to admit wrongdoing.

If those changes are not made, additional sanctions could be levied, and the AG’s office said it could even void the settlement, although a spokesman for the office would not comment further, saying the case is technically still open.

O’Neil and Stowell, in a 90-minute joint interview with the Maine Sunday Telegram, denied they did anything wrong and said the organization is better off because of their actions.

Lawyers familiar with the Maine Nonprofit Corporation Act, though, said the case involving Friends of Maine’s Mountains sheds light on how nonprofit organizations – particularly smaller ones – can operate even with clear conflicts of interest and little financial accountability.

Brent Singer, an attorney with the Bangor law firm Rudman Winchell who specializes in providing legal assistance to nonprofit organizations, called the case startling.

“For (the attorney general) to get this involved, to me, it signifies that something must have been even more ‘rotten in Denmark,’ so to speak, than even appears on the face of the settlement agreement,” he said. “I think (O’Neil and Stowell) were probably lucky this is all that happened.”

A PERSONAL STAKE

Rand Stowell founded Friends of Maine’s Mountains in 2009 with a stated mission of educating the public about the perils of industrial wind development and challenging specific projects.

But he had a personal stake, too. At the time, he owned land adjacent to the Saddleback Ridge wind project.

His family has long ties to the western Maine mountains and once was among the state’s largest landowners, most of it through a company called United Timber.

Stowell took over as president of United Timber in 1968 after his father’s death and ran the company and its subsidiaries until 1998, when it went bankrupt. According to press accounts, the failure to modernize a lumber mill in Dixfield was to blame.

That bankruptcy led to the sale of 91,000 acres of timberland to an Alabama investment firm and the sale of the Dixfield mill to Irving.

Stowell and his wife, Susan, also filed for bankruptcy in 2004 and turned over all but a small parcel of land in the town of Weld to Webb Lake Woods, a company owned by Linda Bean, granddaughter of L.L. Bean and a well-known Maine businesswoman.

Since then, Stowell has been involved in two other failed business ventures. One business, Microptix, went bankrupt in 2013. Another, Predictive Control, which developed software, folded as well. Two former employees of that company sued Stowell for not paying them.

When Stowell created Friends of Maine’s Mountains, he installed himself as president and treasurer, an unconventional arrangement that gave him sole responsibility over the nonprofit’s finances.

Chris O’Neil joined Friends of Maine’s Mountains in 2010, as a board member and also as a contractor for lobbying and public relations.

He became the public face of the group, testifying often at the State House on energy and environmental legislation and reaching out to the media as the voice for wind opposition.

O’Neil had extensive State House experience. He represented Biddeford in the Maine House for four terms between 1996 and 2004, then became a lobbyist, first for Drummond Woodsum, one of the state’s biggest government relations firms, and then on his own.

His clients have included the Maine Appalachian Trail Club, Maine School Management Association, State Farm Insurance, Aetna and the Passamaquoddy Tribe of Pleasant Point.

His lobbying earnings peaked at $161,000 in 2007, according to Maine Ethics Commission records, but dropped to just $4,500 in 2012.

The 2012 total did not, however, include his fee as government relations liaison for the Portland Regional Chamber of Commerce. There is no disclosure requirement for lobbying at the local level.

O’Neil briefly became the face of the anti-casino movement in 2011. He was hired as chief lobbyist and spokesman for a political action committee, Mainers Behind a Rotten Deal, formed to oppose development of a slot machine parlor in Biddeford.

O’Neil’s task was to warn about the dangers of gambling, but it was revealed that nearly all of the contributions to Mainers Behind a Rotten Deal came from another political action committee, Friends of Oxford Casino, whose funders were the investors in what is now Oxford Casino.

In other words, O’Neil was being paid by gambling interests to oppose gambling.

He has defended the apparent conflict, saying that casino supporters had deep pockets and taking their money was the only way to compete.

O’Neil would say essentially the same thing about Friends of Maine’s Mountains accepting wind money.

A SMALL NONPROFIT

Although it formed as a statewide organization, Friends of Maine’s Mountains has formally appealed only two wind projects to the Board of Environmental Protection in its five-plus years of operation: Saddleback Ridge in 2011 and a project in Bingham being developed by Blue Sky West, a First Wind subsidiary, in 2014.

Much of its time has been spent fighting the Saddleback project.

Portland attorney Rufus Brown did the legal work for the group’s appeal, first to the Board of Environmental Protection and later to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court.

The group won a partial victory in 2012 when the court ruled that the project needed to adopt lower maximum decibel levels for nighttime operation.

But Brown said he grew weary of Friends of Maine’s Mountains.

“I had some real professional issues with them, especially with (Stowell),” said Brown, who would not give specific examples, citing attorney-client privilege. “I just couldn’t work with him.”

Friends of Maine’s Mountains started small. In 2009, the year it was founded, contributions totaled $17,350, according to its filings with the Internal Revenue Service.

The next two years, donations jumped to $100,745 and $92,364, respectively, before falling back to $47,517 in 2012.

In 2013, the most recent tax filing available, Friends of Maine’s Mountains took in just $37,942 and ended the year $44,683 in debt.

The big fundraising spike in 2010 and 2011 was attributable to a single donor, an anthropologist named George Appell who specializes in the study of Borneo – the largest of Asia’s islands – and a previous investor in one of Stowell’s companies. He said he donated $244,000 from April 2010 though June 2013.

About 43 percent of that, $103,000, went to O’Neil for lobbying and public relations.

But Appell said he stopped giving in 2013 because he grew concerned about how Stowell and O’Neil were running the organization.

“I have a business background, and I expect things to be run a certain way,” said Appell, who lives in Phillips. “I didn’t think things were going well.”

Appell said he didn’t like that Stowell served as president and treasurer and that O’Neil was both a board member and paid contractor.

Appell said he still opposes wind but wants nothing to do with Friends of Maine’s Mountains because he doesn’t believe the organization has any credibility.

Membership of the board turned over nearly every year, with the exception of O’Neil and Stowell, and finding new members was an ongoing challenge.

Kevin Gurall of Springfield, an early supporter of Friends of Maine’s Mountains, said he was asked to join the board but declined.

“I just did a little bit of digging and didn’t have to dig far to see that things were not being done as they should be,” Gurall said. “And there didn’t seem to be a lot of consideration given to other members’ thoughts.”

Gurall said the group under Stowell and O’Neil’s leadership seemed too focused on one project – Saddleback Ridge – and was not successfully building statewide support.

Stowell, however, said that finding board members was difficult because of the time commitment and blamed turnover on the fact that the wind opposition has always been fractured.

“It’s pretty tough to get some of them to join anything,” he said.

Others, he said, “just weren’t a good fit.”

CONFLICTS WITH BOARD MEMBERS

Mike Bond, an anti-wind activist who divides his time between Maine and Hawaii, started showing up at legislative hearings in 2013 to testify against wind power development. That’s how he met O’Neil and Stowell.

Bond said his views fit with what he thought was Friends of Maine’s Mountains’ mission – to educate about industrial wind and oppose the installation of turbines across Maine’s unspoiled terrain.

When they asked him to join the board of directors, Bond agreed. He was joined later that year by Richard McDonald of Kennebunk and Paula Moore of Orono.

At that time, the two big issues were finding donors and deciding whether to continue fighting what looked like a losing battle with Patriot Renewables over the planned installation of 12 wind turbines near Stowell’s property.

Friends of Maine’s Mountains filed an appeal of the project to the Board of Environmental Protection. That appeal was rejected, but the case went to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court.

The court ruled in favor of Friends of Maine’s Mountains on its concern over noise levels and sent the case back to the BEP, which then reapproved the project with lower noise level maximums.

The law court ruling bought Friends of Maine’s Mountains time, but now it had to decide what to do next.

O’Neil and Stowell acknowledged that Patriot Renewables offered early on to settle the appeal. But they said it was never really an option until it was clear they were not going to block the project in court.

The new board members were all opposed to settling.

“You can’t battle something you think is wrong and then take money from the people you’re battling,” Bond said.

Previous board members had expressed the same concerns.

Former member Karen Pease declined to comment for this story, but in a letter she sent to O’Neil and Stowell in 2011, which was obtained by the Maine Sunday Telegram, she indicated she was also strongly opposed to settling.

“As desperately as FMM needs funds to pay our debts and move forward, I can’t support selling out – and yes, that’s exactly what it will be. Selling out,” she wrote.

She said a settlement would forever taint the organization and instead wanted to let Patriot offer a written deal and then go public with that offer.

“I would hold a press conference and I would make the most of the fact that wind developers are offering huge bribes to neutralize or remove their opposition,” Pease wrote.

That never happened.

In fact, O’Neil and Stowell began pushing hard for a settlement, seeing it as the only way to regain financial footing.

Bond had another idea. He offered to donate $50,000 and match other contributions – if Friends of Maine’s Mountains rejected the settlement.

Stowell, meanwhile, tried to persuade McDonald to consider settling, recognizing that he and O’Neil needed only one more vote for a majority.

In an email to board members Jan. 22, Stowell hinted at a $100,000 contribution, “with some conditions.”

That contribution, McDonald said, was to come from Stowell himself, but only if Friends of Maine’s Mountains settled with Patriot – a deal that would also trigger Stowell’s personal settlement.

A DISPUTED SETTLEMENT

The settlement discussion fractured the Friends of Maine’s Mountains board irrevocably.

Bond, McDonald and Moore exchanged emails about possibly removing Stowell as president and terminating the organization’s contract with O’Neil.

McDonald and Stowell also exchanged tense emails on Jan. 24. McDonald claimed Stowell’s role as president, along with his personal lawsuit, created a conflict.

In particular, McDonald raised concerns about how Stowell could vote on a financial settlement that would trigger a payment to himself.

That same night, Bond wrote an email to Jay Cashman of Patriot Renewables letting him know that a majority of the board did not support settling.

“Please cease in your attempts to pursue these discussions,” it read, referring to settlement talks. Bond, McDonald and Moore hoped the email might scare Cashman off.

The next day, Stowell wrote to all board members that they needed to consider “the best interests of the corporation.” He also mentioned creditors of Friends of Maine’s Mountains who had been “growing less patient.”

They all agreed to hold a special board meeting Jan. 29, but Bond, McDonald and Moore never made it to the meeting. They were each sent letters saying they had been removed from the board by an executive committee made up solely of O’Neil and Stowell.

O’Neil and Stowell then elected a new board member, Daryl Sleight, and promptly voted to accept an agreement with Patriot.

Bond was apoplectic.

“I’ve been fighting environmental battles since the 1960s. I don’t usually get fooled,” he said. “But I didn’t think anyone could be that maleficent.”

Bond said he doesn’t know the specifics of the final deal.

He said when he was on the board, the offer from Patriot was at least $200,000 and perhaps as much as $500,000.

“The money kept going up because we were opposed,” he said.

He said he believed Patriot’s agreement with Stowell was in the hundreds of thousands as well.

O’Neil, who was paid $24,000 in outstanding fees from the settlement, called the executive committee action extraordinary but necessary because the other board members had become “seditious.”

When asked whether he felt right voting on something that would benefit him financially, O’Neil said: “Is that a benefit? To get my bill paid?”

O’Neil and Stowell’s response to criticism of their actions was simple: The law allowed them.

“Given the alternative of destroying or preserving the corporation, the lawful removal of seditious directors was the only option,” O’Neil said.

O’Neil and Stowell also said Bond, McDonald and Moore were aware of the organization’s bylaws and the existence of an executive committee.

“It’s not a democracy,” Stowell said. “It’s a corporation.”

As for the settlement, O’Neil said: “In my estimation, it enhanced our credibility. It showed that we’re adults who know how to make sound business decisions.”

Others, however, see it otherwise. Singer, the Bangor attorney, said he was shocked that O’Neil and Stowell ousted the other board members to get what they wanted.

Dan Boxer, an adjunct professor of governance and ethics at the University of Maine School of Law, said Stowell has a long history of service on boards, and O’Neil is a former lawmaker.

Both should have known better than to operate the way they did, he said.

“This is among the least transparent organizations I’ve seen,” Boxer said. “Nothing was done well.”

AN ‘APPEARANCE OF CONFLICT’

Bond, McDonald and Moore had no power to reverse what happened, but they brought their case to the Attorney General’s Office.

Assistant Attorney General Christina Moylan, in a March 18, 2014, order approving the investigation, concluded that both O’Neil and Stowell were creditors with a direct personal interest.

“Neither should have been deliberating or voting on any proposed action to accept a settlement,” she wrote.

That investigation took nearly a year, but the Attorney General’s Office concluded that O’Neil and Stowell participated in improper conflict-of-interest transactions and improper governance transactions.

Nonprofits are governed by the Maine Nonprofit Corporation Act, which has a conflict-of-interest provision that doesn’t outright prohibit a board member from being paid but says any transactions must be disclosed and approved by the full board. Violations don’t often make it to the Attorney General’s Office and when they do, they are pursued with a goal of remediation, not harsh punishment.

The settlement agreement with Friends of Maine’s Mountains was structured to “not constitute an admission by any party,” but it did order the nonprofit to change its entire operation, including adopting a conflict-of-interest policy, eliminating any bylaw language that allows for an executive committee and documenting its finances better.

Both men would have to vacate the board within four months of the settlement, signed in late February.

O’Neil and Stowell were represented in the settlement by Severin Beliveau, one of Maine’s most powerful lobbyists and dealmakers, with longstanding ties to Attorney General Janet Mills and a family friend of Stowell’s.

He said his clients never saw the allegations as serious violations but were glad to settle.

“The alternative would have been to go to court,” Beliveau said. “That would have been a nonprofit with little resources going up against two lawyers from the Attorney General’s Office.”

If the changes requested by the attorney general are not made, Friends of Maine’s Mountains could be penalized further.

O’Neil and Stowell defended their actions and said they believe they would have won in court.

Asked whether they thought anything they did was unethical, O’Neil and Stowell said only that they did nothing illegal.

“They didn’t take us to court,” O’Neil said.

O’Neil, though, said he’s unlikely to work again for an organization that he also serves as a board member.

“The appearance of conflict is one no one wants,” he said.

Boxer, the UMaine law professor, said the conflict was real, not an appearance.

“(Maine’s) nonprofit law is better than nothing, but it is still weak and enables sloppy governance,” Boxer said. “However, I think what they did goes well beyond sloppy.

“It seems, arguably, an intentional and very non-transparent diversion of what should have been organizational assets from the settlement for personal benefit.”

He said he may even use the nonprofit as a “mini case study” in his class about what not to do.

The settlement money gave Friends of Maine’s Mountains a boost, but much of it was used to pay debts, including to O’Neil. Even he and Stowell acknowledged that the settlement doesn’t solve their money problems in the long term.

However, O’Neil hinted that more money might be coming to Friends of Maine’s Mountains. In early March, about a week after the settlement with the Attorney General’s Office, the group dropped its appeal of the Bingham Wind Project.

Asked why, O’Neil said he couldn’t discuss it but said, “It’s going to be really good news.”

O’Neil and Stowell also said they have yet to recruit any new board members as ordered by the Attorney General’s Office, although that could happen as soon as next month, according to O’Neil.

The organization plans to keep opposing the development of wind power in Maine and recently drafted a bill, sponsored by Rep. Beth O’Connor, R-Berwick, that seeks to make it harder for wind developers to do business in Maine.

And O’Neil said he’ll continue to serve as lobbyist and spokesman at Stowell’s pleasure.

Bond and McDonald, meanwhile, have put their efforts into another anti-wind group, Saving Maine.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.