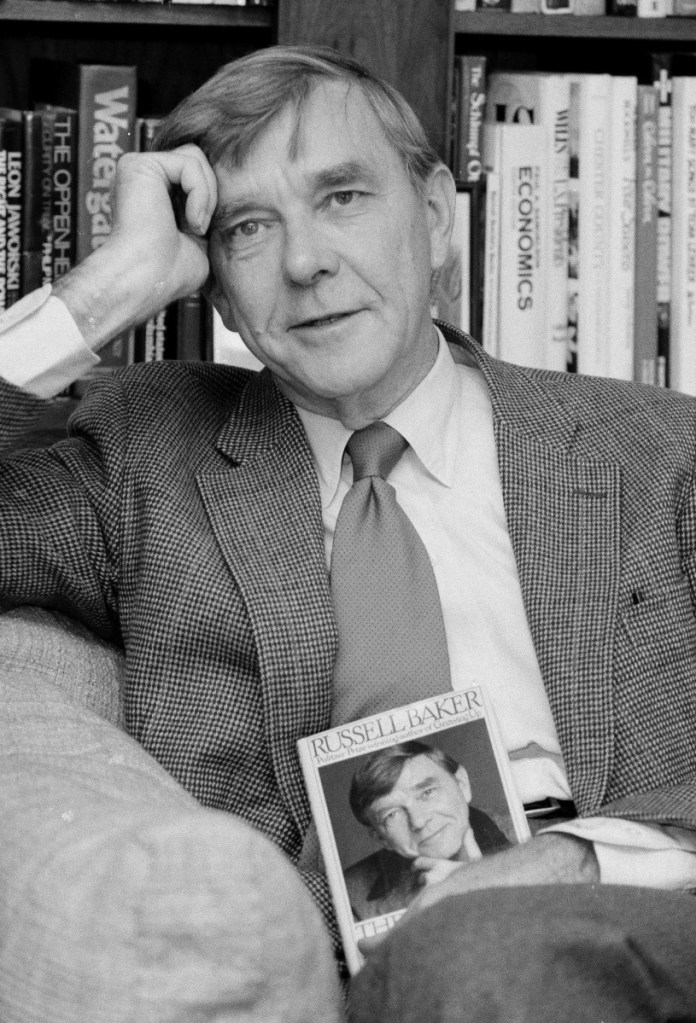

Russell Baker, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer who for 36 years brought whimsy, irreverence and droll commentary to the Observer column in the New York Times and whose memoir, “Growing Up,” was a bestseller, died Jan. 21 at his home in Leesburg, Virginia. He was 93.

The cause was complications from a fall, said a son, Allen Baker.

Baker, who received a Pulitzer for commentary in 1979 and another for his Depression-era memoir four years later, later succeeded Alistair Cooke as the host of public television’s “Masterpiece Theatre” series.

A Virginia-born humorist who blended self-deprecation and wry wit, Baker wrote in simple, straightforward prose modeled after the effortless grace of E.B. White’s pieces for the New Yorker. Baker termed his thrice-weekly efforts “a casual column without anything urgent to tell humanity.”

The 10 columns the Pulitzer committee examined showed the breadth of Baker’s interests and the range of his writing voice. The subjects included tax reform, loneliness, dying, fear, artist Norman Rockwell, the death of New Times magazine and the difference between being serious and being solemn.

He wrote about ordinary life lived by ordinary people. He never rewrote a column or threw one away, and he took pride in never having stockpiled columns in reserve. “I figure that if I write one and then I die, the Times will get something free,” he once quipped.

His opening lines often contained a pithy one-liner: “Listening to the economics wizards talk about the recession, you get the feeling that things are going to get better as soon as they get worse.”

In one column, he lampooned the burgeoning pomposity in American speech.

“Americans don’t like plain talk anymore,” he wrote. “Nowadays they like fat talk. Show them a lean plain word that cuts to the bone and watch them lard it with thick greasy syllables front and back until it wheezes and gasps for breath as it come lumbering down upon some poor threadbare sentence like a sack of iron on a swayback horse.”

And in another, he went after the unwillingness of Congress to approve legislation putting warning labels on used cars.

“Put yourself in the Congressman’s shoes,” Baker wrote. “One of these days he is going to be put out of office. Defeated, old, tired, 120,000 miles on his smile and two pistons cracked in his best joke. They’re going to put him out on the used-Congressman lot. Does he want to have a sticker on him stating that he gets only eight miles on a gallon of bourbon? That his rip-roaring anti-Communist speech hasn’t had an overhaul since 1969? This his generator is so decomposed it hasn’t sparked a fresh thought in fifteen years?”

But he could also express shame and outrage when the subject warranted it, as witnessed by his meditation on inflation and its effect on old people watching their pennies in the supermarket: “Staring at 90-cent peanut butter. Taking down an orange, looking for its price, putting it back. . . . Old people at the supermarket are being crushed and nobody is even screaming.”

Baker understood poverty, after spending his earliest years in rural Loudoun County. “I had one foot back there in this primitive country life where women did the laundry running their knuckles on scrub boards and heated irons on coal stoves,” he wrote in “Growing Up,” his grim and vivid 1982 autobiography.

The memoir, which sold more than 1 million copies, was “among the most enduring recollections of American boyhoods – those of Thurber and Mencken, Aldrich and Twain,” book critic Jonathan Yardley wrote in his review for The Washington Post.

His strong-willed mother left the greatest impression on Baker. “I would make something of myself,” he wrote in the book, “and if I lacked the grit to do it, well then she would make me make something of myself.”

After Navy service in World War II and with a degree from Johns Hopkins University, Baker joined the reporting staff of the Baltimore Sun in 1947. An aspiring novelist, he advanced within five years from cub reporter to London correspondent – in time to cover a coronation.

“It was Queen Elizabeth who made me a foreign correspondent,” he wrote decades later in the Sun. “Before she turned up, my newspaper career had consisted of listening to Baltimore policemen reminisce about great hangings and covering bush-league statesmen deploring the state of the world.”

He was a White House reporter for the Sun before joining the Times’s Washington bureau at 37. He grew bored covering Congress, which he wrote amounted to standing in corridors “waiting for somebody to come out and lie to me.”

The Sun attempted to lure him back with an offer of a column of his own choosing. He was about to accept when Times publisher Orvil Dryfoos stepped up with a matching offer, giving Baker a regular spot on the paper’s editorial pages. The column was called the “Observer,” and it would become a Times staple for decades.

Baker’s first column appeared on July 16, 1962, and it was a sendup of the answers, mostly quips, actually, that President John F. Kennedy might put forth at his news conferences. Baker’s short, sprightly sentences and plain English signaled a departure from the dry, complex and solemn writing that was the standard Times approach of the day.

Russell Wayne Baker was born in the Loudoun hamlet of Morrisonville on Aug. 14, 1925. His father was a stonemason who had diabetes as well as a proclivity for moonshine. The combination of the two killed him at 33. Russell was 5.

Facing destitution after the death of her husband, Baker’s mother took dire measures.

She offered her youngest daughter, Audrey, for adoption by her brother-in-law and his wife. With her remaining children – Russell and his younger sister Doris – she moved to New Jersey to live with a brother who, in those Depression-era days, was one of the few family members to have a job.

Russell, Doris and their mother moved to Baltimore in the mid-1930s and subsisted for a time on government-surplus food. Baker earned an academic scholarship to Johns Hopkins but left college in 1943 to enlist as a pilot in the Navy during World War II. He was never deployed overseas. He finished his degree after the war, in 1947.

In the early 1990s, Baker’s career took an unexpected turn when the producers of the venerable PBS program “Masterpiece Theatre” asked him if he would be interested in replacing the retiring Cooke, the erudite, silver-haired British broadcaster, as the show’s host.

He initially laughed at the notion saying, “I don’t want to be the man who follows Alistair Cooke. I want to be the man who follows the man who follows Alistair Cooke.”

Nonetheless, Baker accepted the job and served as host from 1993 to 2004, introducing Shakespearean plays, dramatizations of novels by Charles Dickens and P.G. Wodehouse and the “Prime Suspect” detective series, among other productions.

In 1950, Baker married Miriam “Mimi” Nash. She died in 2015. In addition to his son, of Manhattan, survivors include two other children, Kasia Baker of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, and Michael Baker of Morrisonville; two sisters; and four granddaughters.

Baker received a prestigious George Polk award for his career achievement in 1999. He wrote several other books, including compilations of his columns and two other memoirs, “The Good Times” (1989) and “Looking Back” (2002). He was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books.

“I’ve always felt that journalism ought to be a little spontaneous, and I want my stuff, which is a very personal kind of journalism, to reflect how I feel at the moment,” he told Esquire magazine in 1979.

His column, which last appeared on Christmas Day 1998, frequently gave him that opportunity. One of his columns from April 1977 included his ode to the Internal Revenue Service. He called it “A Taxpayer’s Prayer”:

“O mighty Internal Revenue, who turneth the labor of man to ashes, we thank thee for the multitude of thy forms which thou hast set before us and for the infinite confusion of thy commandments which multiplieth the fortunes of lawyer and accountant alike. . . . Grant that this sacrifice not be found insufficient unto thy auditor.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.