Schools in Maine have closed their doors on the 2021-2022 school year, one of immense challenge and tumult.

And educators are frustrated, tired and burned out.

As schools opened last September, it looked for a moment like everything might go back to normal. Following a year and a half of remote and hybrid school brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, students were heading into a year that promised a return to in-person learning and fewer COVID-19 disruptions. In some ways this year did provide a return to the pre-pandemic status quo. But it also offered a new array of challenges.

Across the state, educators dealt with the continued presence of the virus, students who needed more mental health support and academic help, renewed concerns about school safety, and heightened criticism from parents, community members and political groups about how they do their jobs. And those challenges were not unique to Maine.

One major indicator that teachers are struggling across the country is the mass exodus of educators from the profession. A majority of teachers – 55 percent – are thinking of leaving the field earlier than they had planned, according to a February National Education Association survey. That’s up from 37 percent last August. The National Education Association is the country’s largest teacher labor union, representing around 3 million educators.

Although there’s no question that the pandemic brought snowballing challenges to the education profession, the year had its silver linings.

In-person graduation ceremonies returned, teachers saw students recover ground academically and, for some, the pandemic highlighted the importance of their work and the services that public schools provide, inspiring them to work harder than ever for their students.

To understand what they faced and how they got through it, the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram spoke with 10 educators from around the state about a school year they’ll likely never forget.

Eric Brown poses for a portrait in the classroom he’s taught in for the last 28 years at Lawrence High School in Fairfield. “My experience is in teaching my subject matter, but now I’m also trying to understand how to support these students socially,” he said Michael G. Seamans/Morning Sentinel

ERIC BROWN, high school science teacher in Fairfield

This year was the first time in 28 years of teaching that Lawrence High School science teacher Eric Brown ever thought, “I don’t want to go to work.”

It was in November, standing in his kitchen drinking coffee before leaving for the day. Brown, 55, said he loves his job. He finds it rewarding and fun. But this year was hard.

It was exhausting to fight with kids every day over masking, to cover for other teachers during his prep time because there weren’t enough substitute teachers, to support students with increased mental health needs at the same time as trying to get through his curriculum and to engage students who he said were more apathetic than ever.

“I would be lying if I didn’t say this year was especially taxing,” he said.

Brown has a mantra he uses to keep himself motivated. Every day he tells himself that he’s going to go to work and be the light in somebody’s darkness.

“This year I had to work harder than ever before to show up with that attitude.”

Figuring out how to best support his students’ mental health was one of the most difficult components of the year for him, he said.

“My experience is in teaching my subject matter, but now I’m also trying to understand how to support these students socially and emotionally,” he said. “It’s a huge extra task, and veteran teachers like me aren’t really trained for it.”

But he said he could see how much the students needed it. There are always some students who don’t want to do their homework, but he said the apathy he saw from students this year was more extreme than that – students that wouldn’t pick up their pencil, wouldn’t answer basic questions, wouldn’t participate in any classroom activities.

He remembers one student who just sat staring at a cellphone and not responding as he spoke to them about the need to join classmates in a science activity. Brown said he saw this type of behavior throughout the year from multiple students.

“I never saw anything to this extent and it was frustrating to see them so disengaged,” he said. “But I could see it was really important to make every effort to reach them.”

Brown said educators do their best when students are in school – providing them breakfast and lunch, teaching them academic skills and trying to support their mental health.

“But schools are not magical. I’m not a magician,” he said. “We can do what we can when students are in school, but for the rest of the hours of the year we don’t have control. We can see students are not getting what they need and, if they’re struggling so much, something in society needs to change.”

– Staff writer Lana Cohen

Gorham Middle School teacher Amanda Cooper sorts through papers on her desk while cleaning her classroom for the summer break. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

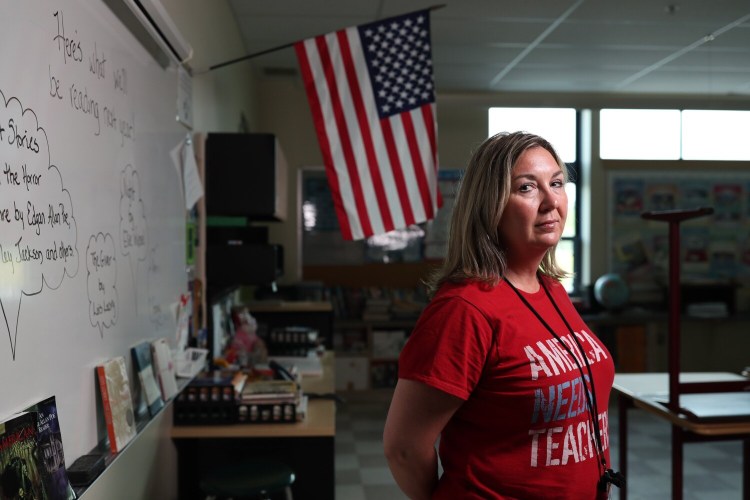

AMANDA COOPER, Gorham Middle School teacher

Amanda Cooper, who teaches English and social studies to eighth-graders at Gorham Middle School, said it’s a tough time to be a teacher.

“In some regards, my resolve is stronger than ever, because I know that children need me,” said Cooper, 46. “And then there are other moments when I wonder, ‘Am I really making the difference that I need to be?’”

In December, a threat sent Gorham middle and high schoolers home early – Cooper, who has been a teacher for 21 years, said it was the first time that had happened in her career. When she saw the Texas shooting on the news, she just cried.

“I shouldn’t have to come in here every single day and think about, ‘What do I do if?’” she said. “That’s not what I signed up for. … I don’t know the answer to it, but I know that it has to stop.”

It’s one of the biggest reasons she’s considered leaving teaching, she said.

“I would say I’m kind of the quintessential Maine girl. … My family hunts, I grew up with guns in my home, I’ve shot guns,” she said. “But … the concept of shooting children is just so hard to wrap your head around because they’re just somebody’s babies.”

Students fully returned to classrooms at the end of the last school year but had greater needs academically, socially and emotionally, Cooper said.

On top of navigating COVID-19 protocols, Cooper said she had to more explicitly teach school routines and skills – academic stamina, turning in work on time, how to behave in the hallways – and also help students build relationships with each other.

“In years past, I wouldn’t think twice about assigning students to read 20 pages in a novel,” she said. “This year, I’m finding it’s a stretch to get 12 out of them.”

There were days when she taught two classes at once, when her teaching partner next door couldn’t come in – substitute teachers were tough to find this year, she said.

“I literally taught in that doorway to 46 kids,” Cooper said. “I’m teaching English in this room and science in this room, allegedly. Really, just managing crowd control. In those days, you kind of are like, ‘what is this? What am I doing?’”

Hope comes in small doses, from the students, Cooper said.

“It can be really hard and it can make the job not seem worthwhile,” she said. “And then a kid comes along and saves you. … You see them make that growth, you see them get that concept, you see them develop that confidence, and then you realize that this is why I do this.”

– Staff writer Claire Law

Halima Hersi teaches English language learners at Robert V. Connors Elementary School in Lewiston. She said the pandemic exacerbated behavioral issues for some of her students. “We just have to be patient with them.” Derek Davis/Staff Photographer

HALIMA HERSI, Lewiston primary grades teacher

Halima Hersi teaches English Language Learners in kindergarten and first and second grades, and said she focuses on staying positive for the sake of the kids.

“At the end of the day, the face that they’re looking at is my face,” said Hersi, who teaches at Robert V. Connors Elementary School in Lewiston. “If I’m positive, then, you know, that’s what they’re going to reflect on.”

This was Hersi’s second year as a teacher – and the first with all her students in the classroom. Hersi, 35, who had worked in the district as a substitute teacher and interpreter, became a full-time teacher earlier than planned because of staff shortages and is now teaching while finishing her master’s degree at the University of Southern Maine.

She said there were kids who missed out on a lot of learning. Some, she said, particularly those with no English backgrounds, had behavioral issues, struggling to express themselves in other ways.

“They’re good kids. They want to try their best … to adopt school culture and expectations all over again,” Hersi said. “We just have to be patient with them.”

Hersi said the school implemented a language facilitator to help with interpreting after seeing one student experiencing emotional distress as he struggled to adapt to a new environment.

“Everyone was very strategic, trying to make his transition to school a fair one,” Hersi said.

Hersi said it’s up to teachers to be resourceful and find creative ways to teach and support students. She plays background sounds while the kids work and made a “behavioral board” for them to see how their behavior is in the class.

“And just reminding them … ‘Hey, you know, Ms. Hersi loves you,’ kind of thing,” Hersi said. “They know that, each and every day.”

As a former ELL student herself, Hersi said she uses her own experiences to teach. Hersi, who came to the United States from Somalia at 12 years old and spoke no English at the time, said she wants to give her students what she didn’t have growing up.

She said at Connors, teachers and administrators remind each other to be positive.

“When you talk to an administrator who is such a positive, it just changes your work ethic,” Hersi said. “As a teacher and an educator, I just feel like I go above and beyond because of the people that I work with.”

– Staff writer Claire Law

Michael Hale, a counselor at Casco Bay High in Portland, saw students return to in-person class with more anxiety. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

MICHAEL HALE, high school counselor in Portland

More than anything, the challenges of 2021-2022 gave Casco Bay High School counselor Michael Hale a renewed sense of purpose.

It was clear to Hale that when Casco Bay, along with schools across the country, went into lockdown in March 2020, the school and its students were going to lose more than just classroom time.

“School isn’t just a place for academic work. It’s a community,” he said. “And two years without that was hard on everyone.”

For 56-year-old Hale, the year was about rebuilding support systems and connections between students, teachers, parents, mental health support staff and administrators. And it wasn’t easy work, he said.

“A lot of kids, parents and families really struggled being at home,” he said. “Schools provide support systems to families and we could see that there was a negative impact when those weren’t provided.”

Hale said students’ struggles were evident in many ways – increased anxiety and depression, struggling to focus in class. But at the most extreme level were students who simply did not show up to school.

Chronic absenteeism is not a new problem for schools in general, but it escalated in the pandemic. According to a December report from the consulting firm McKinsey and Co., which defined chronic absenteeism as missing at least 15 school days in a year, the percentage of students on track to be chronically absent was 22 percent, double the rate of chronically absent students prior to the pandemic.

Hale said he believes Casco Bay High School had larger numbers of chronically absent students during the last two and a half years than before the pandemic, although there are no official numbers yet.

For one student who wasn’t coming to school and whose parents could not be reached, Hale worked with an adult sibling living states away to help get the student back to class.

For some struggling students, there were daily phone calls and home visits from social workers and teachers. For others, cookies were delivered.

“Every educator was challenged to their core over these past two and a half years,” he said. “It was at times overwhelming and there was a lot of heartbreak. But at the end of the day it just reminded me why this work is so important.”

– Staff writer Lana Cohen

Jake Langlais, Superintendent of Lewiston Public Schools, says that he is exhausted from the challenges of the school year. “It was kind of like running a marathon. Except you didn’t expect to run it, didn’t train for it and didn’t have the right shoes to run it. You just did it anyway.” Derek Davis/Staff Photographer

JAKE LANGLAIS, Lewiston superintendent

Before the pandemic, Lewiston Superintendent Jake Langlais usually got to work around 7 a.m.

But this year his regular start was closer to 5:30 in the morning. That’s when he would get together with a few other administrators to figure out what resources they had to work with for that school day – did they have enough bus drivers to transport students from their homes to their schools, enough teachers to hold classes?

Sometimes the answer was yes, and sometimes the answer was no.

The consistent uncertainty that hung over the school year meant everyone working for the state’s second-largest school district had to be ready to shift gears at any moment and take on tasks they weren’t used to or necessarily qualified for.

And all that was exhausting, said Langlais, 43, who has worked in education for almost two decades. Exhausting for him and everyone he worked with – administrators who stepped into the role of teacher one day and bus driver the next, teachers who used their planning time to cover for colleagues who tested positive for COVID-19 or had to pick up their own children from school, and for everyone who walked into the unknown every day.

On Tuesday, in a final meeting of the school year, Langlais told the district administrative team that it was OK to grieve the year, recognize how hard it had been and commend themselves for putting their heads down and doing everything that was needed to support the district’s students.

“It was kind of like running a marathon,” Langlais said of the school year. “Except you didn’t expect to run it, didn’t train for it and didn’t have the right shoes to run it. You just did it anyway.”

– Staff writer Lana Cohen

“The incoming ninth-graders were like a bunch of hooligans … really not having a clue as to how to behave in a social setting within a school. The last time they were in school was in sixth grade,” said Melissa Luetje, a science teacher at Kennebunk High School. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

MELISSA LUETJE, Kennebunk High School teacher

For Melissa Luetje, who teaches science at Kennebunk High School, the pandemic has meant focusing on the holistic success of her students, not just the academics.

Luetje, 51, said she has let go of the pressure to teach all the specific topics in class she used to cover, and now also focuses on teaching her students “critical skills.”

“Being able to do that has just put what I do now in a different perspective,” she said. “Before, it was so content-based and content-focused.”

Luetje and her colleagues in the science department changed the curriculum to be structured around fundamental skills kids should know when they leave in June, whether they’re social-emotional skills or lab-based science skills.

“Now, there’s not hordes of kids in (class) making up labs and getting extra help on this or that,” said Luetje, who has been teaching for 19 years. “That happens, but it’s not a high-pressure situation. Now, it’s just more thoughtful.”

This year, students had increased anxiety about workload, absences were high and adhering to deadlines was a rarity, Luetje said. Pushback against boundaries and authority was amplified, especially with younger students, Luetje said, pointing out a food stain on a stairwell wall in the building.

“The incoming ninth-graders were like a bunch of hooligans, walking around and really not having a clue as to how to behave in a social setting within a school,” she said. “The last time they were in school was in sixth grade … they didn’t have the opportunity to learn social norms.”

She said it was gutting to see teachers face disrespect from some members of the community and school board throughout the pandemic.

“When you feel undervalued and disrespected by the people, the community that you serve, and the board that oversees the district, it’s incredibly disheartening,” she said.

There was backlash against teachers for not wanting to be in person five days a week before they had access to vaccines, she said. Some groups also have tried to limit what topics they teach.

“It’s about having the students be successful and ready to go on to their adult life,” she said. “They can’t do that if I can’t talk about racism, … can’t have a conversation about being a transgendered youth.”

In May, Kennebunk High School students staged a walkout to protest the overturning of Roe v. Wade, following the leak of the Supreme Court draft. Luetje said she was proud of students for voicing their opinions and that public education should provide space for that to happen, so that they can provide students guidance.

“Allowing them to have a healthy outlet like this, whether it’s through art or staging a walkout is a worthwhile endeavor,” she said. “We’re helping them navigate that in a healthy way.”

With her new perspective on teaching, Luetje is hopeful for the future.

“I’m proud as hell of my profession,” she said. “Next year … I’m ready to change it up again and just continue forward, knowing full well I’m never going back to the way that it was.”

– Staff writer Claire Law

SOPHIE PAYSON-RAND, Portland schools social worker

Before the pandemic, Portland High School social worker Sophie Payson-Rand worked regularly with 50 to 70 students a year. But this year her caseload was closer to 120 students.

“It was constant,” she said. “I was super overwhelmed, and I was always worrying that there was someone I wasn’t reaching.”

Sophia Payson-Rand said she took off a few weeks of work to ease the stress of the pandemic – a first in her 30-year career. Photo courtesy of Portland Public Schools

Payson-Rand, 53, was so exhausted that midway through the year she decided she needed a few weeks off, something she had never done before in her 30 years as a school social worker.

“There were so many students and I was just feeling like I couldn’t be fully present,” she said. “I was trying to do too much.”

And then one night she couldn’t sleep at all, thinking about work and about the students.

“I was so worried that I might miss something,” she said. “And if you miss something when someone is in crisis, they could end up causing harm to themselves or someone else.”

That’s when she told her principal that she wasn’t sure if she was being the best social worker she could be and needed to take some time to regroup.

From the first day back in school this year, Payson-Rand said she could see that the students were struggling. They were anxious about being back in person and had a hard time sitting in class for long periods of time and settling back into a structured environment, she said. More students expressed social anxiety and feelings of hopelessness and uncertainty.

Mostly, she said, it seemed as if students lost some of their resilience.

“They were so overwhelmed that things that might have had a smaller impact on them in the past got blown out of proportion,” she said. “So, for example, if they got into a fight with their mom on the way to school, it would be so much bigger.”

Usually at the beginning of the school year there is a honeymoon period where everyone is just happy to be back in school, Payson-Rand said. But she said this year there was a lot of uncertainty and trepidation instead.

“They lost over a year of regular, in-person school. That is a long time,” she said. “Coming back, it took everything they had just to make it through the school day, so when there was something else weighing on them, it was too much,” she said. “So, they needed a lot of support.”

– Staff writer Lana Cohen

Paul Penna, the superintendant of schools for MSAD 6, says the pandemic forced his school district to consider how things could be done differently. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

PAUL PENNA, Bonny Eagle superintendent

Paul Penna said the challenges this year forced the Bonny Eagle school system – teachers, administrators, nurses, support staff, transportation, nutrition – to collaborate in new ways, with each other and with families.

Support staff and administrators often filled in when substitute teachers were difficult to find, said Penna, superintendent of School Administrative District 6. And the district struggled with vacancies and staffing shortages in the transportation department.

Because of these staff shortages, the administration created a new protocol for “remote days,” when either a grade level or whole school had to learn from home, Penna said.

“It used to be … the weather’s too bad, we’re not gonna come to school,” Penna said. “Now, it’s changed to, we’re down staff, we’re down transportation.”

In September, Bonny Eagle schools were closed because of a social media threat.

“Especially in the world we’re living in right now and all that’s happened, you can’t take a threat lightly,” Penna said. “If ever in doubt, you keep your community safe.”

Despite this year’s challenges, the 66-year-old educator said a positive change came out of it – the pandemic forced the district to consider how things could be done differently. Now, instead of strictly following a “cookie cutter approach,” things can be changed to meet different kids’ needs.

“Maybe a student can be in class for the day … other days, maybe they’d be in the office or maybe they’d be with one of the support people,” Penna said. “What people bring to the table is when they personalize what their child needs to be successful in school.”

Penna, who is retiring after 38 years of being an administrator, said he also saw more appreciation from kids and families this year as he visited schools, served lunches or helped with bus duty,

“In spite of all the other things we hear in the media, about, you know, trash talking and beating up school boards … the silent majority is quite positive,” Penna said.

– Staff writer Claire Law

Kyle Smith is a band teacher at Westbrook High School who had to teach band remotely during the pandemic. Just when he and his students thought they would be able to practice in person as a group again, a fire at the school forced them into remote learning for another half a school year. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

KYLE SMITH, Westbrook band teacher

After a year and a half of teaching students in remote and hybrid formats, Westbrook band director Kyle Smith was as eager as anyone to go back to work in person.

The pandemic proved that remote learning has its limits. And that that is particularly true when it comes to teaching the arts – dance, drama, music – activities built on being together.

That’s why Smith, a teacher of 19 years, was so disappointed when he learned in August that Westbrook High School would be remote for yet another semester.

COVID-19 was not the reason that time. An electrical fire severely damaged portions of the school in July, making the building unusable until repairs could be completed.

Smith, 43, was with the school marching band when he heard the news that he was headed into another year of remote learning. Band camp had kicked off a few weeks prior and he was in the school parking lot practicing with his students when the robocall went out.

“I saw their shoulders slump and their heads go down,” he said. “They were looking forward so much to being with other people.”

Smith was ready to go back to in-person school, too.

“It felt like everyone in the world got to go back to school except for Westbrook High School,” he said. “It was demoralizing and defeating.”

Throughout the pandemic, band continued online, but it wasn’t the same, Smith said. Students played their instruments “together” over Zoom, but they all had to be on mute. And the strong community that band had provided for so many students prior to the pandemic wasn’t there.

Westbrook had a band program when Smith first started teaching there back in 2006. But the skill level of the students was very low, he said.

Over the past 16 years, Smith and his wife, Krystle Smith, who is the middle school band director, have been slowly building up the program. And although this year was a successful one for the Westbrook band department, with gold medals and other awards, the program lost of a lot of ground during the 689 days without regular in-person band practices, Smith said. Fewer students came back to band and many of those who did had lost ground.

“Their skill level was so low it was really like having a sixth-grade band in high school,” Smith said. “We did 15 years of hard work and then we just ended up back at square one.”

– Staff writer Lana Cohen

Rob Taylor, a teacher at Spruce Mountain High School, missed the last two weeks of school after getting COVID. He returned on the last day of final exams. Derek Davis/Staff Photographer

ROB TAYLOR, Jay high school science teacher

Last year, teachers designed their lessons for remote or hybrid instruction. This year, lessons were prepared for the physical classroom – but students and teachers were often out sick.

Robert Taylor, 55, a science teacher at Spruce Mountain High School in Jay, said faculty in the department often covered for each other. One day, he went straight to work after being discharged from the emergency room – if he didn’t, another teacher would have to cover his class because they couldn’t find a substitute teacher, he said.

Trying to keep students engaged while they were home in quarantine was a big challenge.

“If I’m doing a lab in my science class with students or I’m taking kids in my environmental science class out in the field, and I have a couple of students that are out in quarantine, they’re missing those experiences,” Taylor said. “It’s just really, really hard to provide remote instruction while you’re trying to do live instruction.”

By Christmas, six of his students had dropped out of high school after falling behind, he said.

“What I often saw happening was a kid would get behind in class, … then you throw on top of that they get a 10-day quarantine situation because of COVID. Or maybe there’s a behavior issue and something happens with that,” he said. “And before you know it, that kid is … seeing ‘wow, I have all this work I gotta do.’ And it becomes overwhelming.”

Shortly after the May 24 shooting in Uvalde, Texas, the middle school in Taylor’s district responded to two different threats on consecutive days, both of which turned out to be false alarms.

“We’ve been trained a lot and when you see something like that happen in Texas, you become hyper vigilant,” Taylor said. “And then when you have two days of back-to-back threats … it was a very difficult way to end the year.”

Taylor said seeing a mental health professional, which he started doing two years ago because he was struggling with seeing students suffer, helped him through the past few years.

Despite its challenges, teaching is rewarding, said Taylor, who was the 2019 Franklin County Teacher of the Year. The robotics team he mentors ended up 25th out of 182 teams in a New England competition, he said. One of his students who had dropped out of high school, he said, went to the Spruce Mountain Adult Education program afterwards and got a diploma.

“It hurts me when a student drops out, or a student doesn’t do well. On the same token, I’ve had so many experiences this year where kids have overcome so, so much,” Taylor said. “There’s a lot to overcome and there’s a lot to deal with. But to be able to work with young people and see them grow, see them blossom, see them reach their potential. There’s just nothing else like it in the world.”

This story has been updated at 8 a.m. on June 19 to correct the spelling of Michael Hale’s name.

– Staff writer Claire Law

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story