MONSON — Here’s a free tip if you are planning to hike the Appalachian Trail, some 2,200 drenched, sweaty, bug-bitten, frigid, achy – and euphoric – miles up and down and up and down and up and down from Spring Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin: Do not pack in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Luke “Tuna Shorts” Sineath, of Greensboro, North Carolina – a thru-hiker, meaning he’s attempting to complete the entirety of the trail at once – made that mistake.

Because the characters are starving, the novel, set in the Dust Bowl, mentions food again and again, Tuna Shorts discovered to his dismay. Tuna Shorts – that’s Sineath’s trail name, all hikers get one and use it in place of their “civilian” or “government” names while on trail – was relating this story around 7 a.m. on a morning in mid-September over the legendary breakfast at Shaw’s Hiker Hostel: three eggs fried in plenty of bacon fat; three slices of bacon; a mound of deliciously oily home fries; strong, bottomless cups of coffee; and as many fat, fluffy blueberry pancakes as a hiker can eat. He was aiming for 11.

For northbound hikers, the hostel is the last stop in town, the last civilization, before the remote and beautiful 100-Mile Wilderness, itself the last stretch of their five- to seven-month trek. Tuna Shorts set “The Grapes of Wrath” aside. “I can’t read this right now because I am starving too!” The table of hikers eating breakfast with him hooted in recognition. Tuna Shorts has lost 30 pounds on the trail, about average according to a fact sheet put together by outdoor gear company REI. Other hikers that morning, a few men painfully thin, talked about shedding as much as 70 pounds, their hip belts, which carry the weight of their packs, cinched as tight as they go but still swimming on them.

It’s little wonder that Samantha “Ginger Bear” Conner, a section hiker from Chicago – meaning she’s completing the trail in chunks over time – put it, for Appalachian Trail hikers food “is the center of everything.”

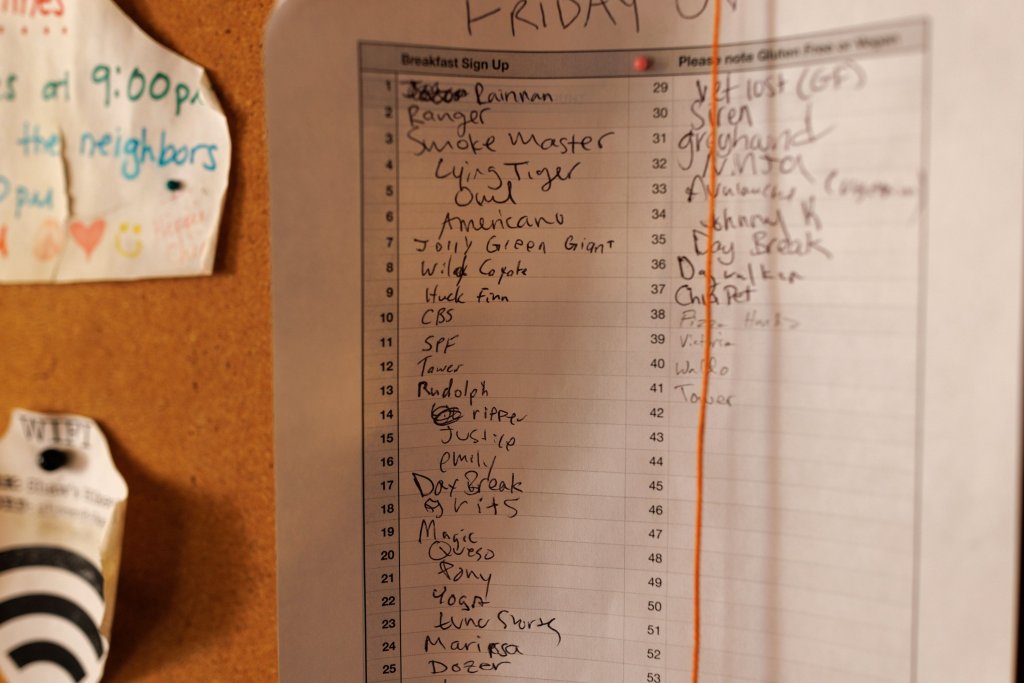

Hikers chat while they wait for their breakfast at Shaw’s Hiker Hostel. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Wesley “Dozer” Moore, of Charleston, South Carolina, recalled a moment he was hiking through the Roan Highlands of Tennessee, some 1,100 miles to the south. Dripping wet and ravenously hungry, he tried, hands fumbling, to unwrap a Snickers bar, a popular trail snack. He badly needed the boost. But the chocolate had melted, then re-solidified, stubbornly sticking the bar to the wrapper. Dozer gulped it, plastic and all. More knowing laughter from the table. Thru-hikers have their own specialized, often colorful lingo, and the term for this intense, insistent, immediate need for something, anything, to eat RIGHT NOW is “hiker hunger.”

“You want to eat all the time. You’ve got to feed the fire, and wherever there is food, you are on it like a fly on stink,” said Carey Kish, who hiked the trail in 1977 and again in 2015 and writes a hiking column for the Press Herald. “And the other thing is you think about food all the time. If it has calories in it and it’s edible, you’ll eat it.

“I’m not kidding.”

THE BASIC FOOD GROUPS

Hikers resting, resupplying, drying out and chowing down at the rambling, sociable hostel described some of the more inventive ways that they, or fellow hikers, ensure they get the calories they need, some 3,000-6,000 a day, depending on the hiker’s size and gender, as well as pack weight, terrain and miles hiked. They chug olive oil, eat Oreos as a “side dish” with dinner, guzzle boxes of cake mix shaken with water, and devour tubes of raw cookie dough. They breakfast on candy bars and Little Debbie Oatmeal Creme Pies; it’s an oatmeal product so it’s fine for breakfast, reasons hiker Maddie “Ranger” Zickel, 31, of Louisville, Kentucky.

They add a whole stick of butter to a single freeze-dried meal, and make a “ramen bomb” for dinner, supplementing the instant packaged noodles with half a dozen eggs — keep in mind this is one meal for one hiker. They pack out cans of Betty Crocker frosting, munch numberless bags of chips, and bolt down enough peanut butter to provision an elementary school with PB&Js.

“Most people just eat it by the spoon,” Melton “Grits” Cockrell said of peanut butter, his Southern accent as thick as the spread. The wiry, bearded Grits, 77, is from south Georgia, and said this will be the last of his many AT thru-hikes. “I’ll tell you what. You seen a dog lick a bowl? Wait till you see a thru-hiker lick a peanut-butter cup. He will clean it to the bottom. It will be crystal clean. You can eat off it.”

If you think that thru-hikers get the formidable energy they need to hike as many as 22 miles a day, with loaded packs, in challenging terrain by eating nutritionally correct diets – heavy on the whole grains, fruit, vegetables and healthy proteins; low on the sugar and salt – you’d be mistaken. Fruit and vegetables are too heavy to carry and need refrigeration, making them impractical, impossible really, to lug along. Whole grains require fuel and stoves (more weight) to cook, also human energy to do the cooking, something in short supply after long, hard days on the trail. In fairness, tuna pouches, a healthy protein, are, it’s said, a hiker’s best friend.

Cooper Martin, whose trail name is Huck Finn, organizes and packs up their food for the Hundred-Mile Wilderness before heading back out to the trail. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

As for sugar and salt, they might as well be basic food groups for AT hikers. Sugar offers immediate calories (read: energy). Pop-Tarts and Little Debbie Honey Buns come up a lot when you ask hikers about their diet on the trail. They can tell you exactly how many calories each package of these – and many other manufactured items – contains. The more, the better, WeightWatchers turned on its head.

“I feel like I’m in a calorie deficit most days,” said Kyle “CBS” Duck, of Escondido, California, who has lost 28 pounds since he started the trail. “It’s so much eating throughout the day. Oh man, it’s so much food. It’s just exhausting to eat that much food in a day.”

Honey Buns, by the way, take up a lot of space in a pack, a problem, as space is at a premium. Hikers, like turtles, are carrying their homes on their backs. As he was packing up his food in the morning ahead of hitting the trail again, Cooper “Huck Finn” Martin, 23, of Gainesville, Florida, demonstrated how to pre-squish the iced breakfast pastries, a technique that involved a knife, a hole in the corner and a good thump. Six inches of pastry shrunk down to two or three inches.

As for salt, salty chips provide something few other staple trail foods offer: texture and flavor. Sustain yourself on instant oatmeal and instant mashed potatoes day after day for months, basics that are largely crunchless and bland, and see if you don’t crave chili-cheese Fritos. As he hiked through Vermont, Joshua “Owl” Hunter, of New Jersey, added a bottle of barbecue sauce to his provisions, squirting it on whatever he was eating. “I just saw it at the store and wanted some flavor,” he said.

Anderson “Ripper” Schmittou and his wife Jessica “Justice,” of Nashville, tried another tactic toward the same end one evening. They cooked a “Thanksgiving-esque” dinner, using instant potatoes, turkey Spam and a gravy packet. “Everything just gets kind of bland and flavorless, so we were looking to keep it interesting,” Ripper said.

“I think food on the trail comes in two directions,” said Jonathan “Red Beard” Pinkel, 30, of Lansing, Michigan. “It’s whatever gives you calories but then also what gives you dopamine — happiness. You get really bored and tired of hiking, so anything you can bring with you that spices up your day, whether it be a bag of chips or a candy bar or a beer. Everybody focuses on weight and being ultra-lite but then once you get to the trail, you realize, ‘I would really rather carry this much heavier food that’ll make me happy than just be miserable.’ ”

TRAIL TRADEOFFS

That call, extra weight versus satisfying rations, is just one of many food-related tradeoffs that crop up on the Appalachian Trail. Just before they reached Monson, one group of hikers confronted a far more fraught choice. Standing on the banks of a raging river that crossed the trail – a few days earlier, an all-day torrential downpour had swelled the already high waters – they debated waiting it out a day and hoping the water receded or risking the river. The risk of a wait was serious, too: They had no food for an extra day on the trail. The hikers opted to cross. One forged ahead with a rope. He was swept downriver some 100 feet, they related, but managed, somehow, to scramble up the opposite bank and secure the rope, allowing the others to cross. “We got lucky,” one of the group said.

More typical is the tradeoff between sleeping late versus and having a warming, restorative breakfast. For Dozer, it’s a no-brainer. When he gets up, he adds two Carnation Breakfast Essentials (a protein powder), instant oatmeal, instant coffee and cold water to his water bottle and gives it all a good shake. “My cold breakfast saves a lot of time,” he said. “They call me Dozer because I like to sleep in.”

Pancakes are served to a table at Shaw’s Hiker Hostel on September 22. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

“I want to put my disapproval of Dozer’s breakfast on the record,” hiker Duncan “Packman” Umphrey, 25, of Concord, Massachusetts, interjected to laughter. The two are hiking together, part of the same trail family, or “tramily.” “I am the opposite way. One of the reasons my pack is so heavy is I have an Aeropress.”

When he gets to a town, Packman searches out ground, good-quality dark roast beans. Back on the trail, “I have my 90-minute breakfast. Coffee, maybe some oatmeal, bagels.” And no squishy untoasted bagels for Packman, either. He breaks out stove and pan, and fries them, halved, in lots of olive oil, cut-sides down. “I’m not sure I’d eat it off trail, but on trail it tastes incredible!” he said.

If there’s a continuum from trail gourmet to indifferent eater, CBS is also at the epicurean end of the scale. He carries chili flakes, gingerroot and sometimes raw eggs in his pack. Also onion and garlic, frying them up to add interest to his meals. He loves to cook and said is always thinking about ways to improve his trail meals. Siler “SPF” Sloan, 24, of Black Mountain, North Carolina, who has been hiking with CBS since they passed through Vermont, was listening to his friend. “I’m just eating my instant mashed potatoes while he’s Gordon Ramsay over there,” he said, laughing.

For Matt Hogan, of Portland, who hiked the AT last year, it wasn’t so much certain foods he missed on trail as the act of cooking itself, “proper cooking, a frying pan, a sink, a cutting board. You cannot do more artsy cooking than, I’m boiling water and either I throw the boiling water onto the dry food or I dump the dry food into the boiling water.”

Jarrod Hester begins to cook breakfast in the kitchen at Shaw’s Hiker Hostel. Hester and his wife, Kimberly, known on the trail as Poet and Hippie Chick, both hiked the trail and bought Shaws in 2015, carrying on the big breakfast tradition from previous owners. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

The hot versus cold meals option, by the way, extends into lunch and dinner. Many thru-hikers opt not to carry a stove or fuel in order to save on pack weight. They “cold-soak” their trail meals, a (punishing-sounding) “cooking” technique that works with items like couscous, instant mashed potatoes, ramen packets and dried soup mixes. “Usually when I am eating on trail, I am not eating to enjoy it,” said Joshua “Owl” Hunter of New Jersey, a practitioner of the cold soak (and, incidentally, a hiker who manages to get his share of fruits and vegetables in a novel fashion: He carries jars of baby food). “That’s why you get so excited when you go into a trail town.”

ON THE TOWN

Burgers, fries and pizza are, no surprise, items that hikers gorge on in the spots where the AT crosses into towns. Hikers also mentioned filling up on ice cream, steak, pot roast, barbecue, Chinese food, Thai food, Mexican food, real coffee and all-you-can-eat buffets. But it isn’t just large portions and heavy, greasy, cheesy, filling, spicy, calorie-dense foods they search out when in town. The other thing they crave? The opposite. Fresh fruits, fresh vegetables and salads. What you want, the hikers explained, is whatever you can’t find on trail.

Your body tells you what you need, a hiker explained. The evening before, the hostel, which doesn’t ordinarily serve dinner, had given hikers a free, surprise dinner of burgers, fruit salad and chips. More than the burger, it was the fruit she couldn’t get enough of.

Ben Jenkins, whose trail name is Chia Pet, looks at the food resupply options at Shaw’s. Fruits and vegetables are too heavy to carry and need refrigeration, making them impractical to lug along. Whole grains require fuel and stoves. Hikers need some 3,000 to 6,000 calories a day and eat candy bars, chug olive oil, treat Oreos as a “side dish” with dinner and bolt down enough peanut butter to provision an elementary school with PB&Js. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Packman said he fantasizes about town food when he is on the trail. “I wouldn’t say it’s religious,” he said, thinking for a moment, “but it’s something that has a symbolic significance. It’s the idea of being warm and dry with a hot meal.”

That was the situation for the freshly showered, freshly laundered, freshly rested hikers breakfasting at Shaw’s, where the kitchen and dining areas smell like your favorite diner. The tables have tablecloths and the plates are stoneware. The breakfasts here have been storied for decades. Daryl Witmer, minister at Monson Community Church for 30 years, used to live next to the hostel. The original owner, known in town as Old Man Shaw, would get up at 4 a.m. to start cooking, Witmer said. Shaw apparently had a favorite tale of his own.

A thru-hiker heard that Shaw’s served all-you-can-eat breakfasts, Witmer related. “They’re going to regret that,” the hiker said. When the hiker arrived at the hostel, he tucked into six eggs, two pancakes, sausage, coffee and juice. “The works,” Witmer said. Done, he held up his empty plate, “Let’s do it again.” He finished a second plate. “Cook me up six more,” he told Shaw, saying he was going for the record. Some of the eggs even had double yolks, Shaw would say when telling the story. All in all, the hiker put away 18 eggs. Then he collapsed. The doctor at the hospital later admonished him: “Never try that again!”

“But he lived to tell the tale,” Witmer smiled.

Hikers boots are lined up outside at Shaw’s Hiker Hostel. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

These days, Jarrod “Poet” Hester runs Shaw’s Hiker Hostel with his wife, Kimberly “Hippie Chick” Hester; the two hiked the trail themselves in 2008. Each morning, Poet is at the stove with his crew. As some 50 hikers streamed in for breakfast, he was a center of stillness in the clamor and activity, frying some two dozen eggs at a time without breaking a sweat. “I enjoy it so much,” he said. “It’s my time for meditation. I go into a flow state when I’m cooking.”

An English teacher in Florida for 13 years before the couple bought the hostel — he earned his trail name by writing haiku in shelter lodges at check-in — now, he said, “I figure I can get a job at Waffle House if I need to.” Poet is passionate about the breakfasts he serves at Shaw’s, to more than 3,000 hikers this summer alone. Even though one suspects ravenous hikers would gladly eat a cardboard box, he cogitates on every detail. He knows which side of the griddle runs hot. He checks that pats of butter are properly softened so they will melt nicely on the blueberry pancakes. He insists on strong coffee and Maine wild blueberries. Despite the pot of bacon grease at the ready on the griddle, Hester accommodates vegetarians and vegans. And he has perfected the exact right degree of yolk runniness so that the yolks will mingle with the home fries when hikers fork in. “They deserve the quality,” he said. “They’ve worked hard to get here.”

A server carries breakfast plates to hikers. The home fries get special attention from Jarrod Hester. Hand-cut, parboiled and fried, with garlic, in extra-virgin olive oil, the home fries are served steaming hot, brown and crispy. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

More than any other element, the home fries get his close attention. They are made in three big, beautifully seasoned cast-iron pans, some of which belonged to Old Man Shaw. Hand-cut, par boiled and fried, with garlic, in extra-virgin olive oil, the home fries are served steaming hot, brown and crispy. Hester makes them with Vidalia onions when he can get them, and seasons the spuds with pink Himalayan sea salt. A salt from the mountains for hikers conquering both mountains and dreams.

Out in the dining rooms, hikers’ plates are quickly scraped clean, and the word on repeat is “awesome.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.